Stories of Origin is a new MR series of articles and interviews that explores the lived experiences of both returning and potential migrants and their families. In this two-part story we visit Indonesia and speak with female migrant workers.

Sadiya (29) sits in a corner, her hijab draped differently from what’s the norm in Indonesia. She is seen as a successful migrant. After four years in Saudi Arabia, she has managed to buy land and return for good. And she had made two million Indonesian Rupiah by merely agreeing to work in Saudi.

Hers is the story and dream that drives young women to migrate for work. A belief that short-term overseas employment would be a panacea; to come back and build their dreams on the sacrifices made thousands of miles away. Between that brink of hope, leap of faith and reality, many dreams splinter.

The women

Like most other migrant domestic workers (MDWs) in her Karawang district village, her migration plan was short-term. Leaving behind young children, her plan was to return as soon as set goals were met.

Sadiya considers her migration fruitful, despite the long hours of work and extreme loneliness she faced in the 4 years of employment in Saudi.

“My Arabi (Arab employer) were very good. They paid me on time.” She had to care for five children, three of whom were disabled.

Sadiya says she was happy while there and with what she achieved.

With trepidation we discuss the details of her employment.

“How many maids?”

“Just me.”

She hesitates, before continuing.

“I did everything. It was a two-storey house, so I had to wake up at 5 a.m. and would be done by 11 p.m.”

“You sent money every month?”

“No. Every five or six months. I got 800 riyals monthly, so will save up and send. They promised an increase after two years, but I didn’t get.”

“Did you go for Hajj?”

“No. But they promised me.”

She straightens her back. “I went for Umrah twice. So I am happy.”

“What did you do during your free time? You called our family?”

“I was very lonely,” she says, rubbing her chest repeatedly.

[tweetable]“I had no phone. No friends. No off day.[/tweetable] When they were not at home I would watch T.V. I couldn’t otherwise. And if I wanted to speak to my family, I had to use their phone. I slept on the carpet, on the floor of the children’s room. I missed my daughter a lot, she was just 4 years old when I left her.”

“Do you advise other women about migrating and working?”

“There’s no need. People will do what they have to. I did.”

There is a resignation, acceptance of terms, condoning the lack of rights in degrees. It could be worse.

For instance, Kartini. Her mother, Darasih, awaits her return. “She hasn’t called for so long. And hasn’t sent money either.”

Kartini went to Saudi five years ago; after the first two years, contact dwindled.

Darasih holds up a photo of her daughter Kartini who works in Saudi Arabia. She has neither heard nor received money from her in the last couple of years.

“Where in Saudi?”

“We don’t know. She didn’t tell us.”

“Has the agency helped?”

“No. That agency was blacklisted and already shut down.”

Kartini had remitted money a few times, and that too stopped. “She wanted to leave her employer, and they put her in another house. Since then we haven’t heard from her. In between, once she called from her friend’s phone. We could not even inform her when her father died. And she hasn’t even received her salary in three years,” the mother weeps.

As we sit listening to the ageing mother, neighbours convene, occupying empty spots on rickety benches, shooing away a straying hen and its line of chicks.

They listen with curiosity but not surprise. In a village full of migrants, these stories are common.

Karawang, West Java, where Migrant-Rights.org spent a day, used to be a major supplier of DWs to Saudi. Both religion and economics play a role in encouraging migration.

Families are paid money to seal the contract and the women are recruited. Saudi in particular, and the GCC in general, are seen as a good place to work for young muslim women, despite evidence to the contrary.

[tweetable]Employment in Saudi also comes with an anticipation of doing Hajj. Many employers offer this in the contract and many deliver on the promise.[/tweetable] A journey which would be out of reach for most impoverished Indonesians.

The irony that the Hajj so conducted is not recognised by the Indonesian Hajj board is lost on the workers and their families.

Engkas, who stands at the threshold of Darasih’s home, smiles and insists her migration was good. She had only two stints, and secured her family’s future. She suggests measures to help Kartini. The family looks at her with suspicion. “Are you undermining our worries?”

“No, I’ve been there twice and made a good life. And I know how the system works…” she walks away, not wanting to squabble.

Another neighbor, Itham, stares at her, sucking on a rolled tobacco. “My wife is in Abu Dhabi. She sends money. But no contact. A man answers her phone when I call. I will give you her number, call her when you go back to Arab.”

Everyone has an ‘Arabia’ story.

The Chalo

In a tiny village of a few dozen households, names of Gulf towns roll of their tongues with ease, with nostalgia and often with a sigh. And the chalo (registered recruitment agent) is an important man in the community.

Chalo Omo Wijaya lounges in his sofa. His home is a concrete structure, more whole than other houses in the area. There is a motorcycle and a small garden. Obvious affluence. He has been in the trade since 2000.

Over the doorway, inside his sitting room are three frames – a place of honour next to a tapestry rendition of the Ka’aba.

One frame holds the photo of the couple, one is his agent’s certificate and square in the middle is a photo with the owner of the agency from ‘Arab Saudi.’

This man has been responsible for Omo’s prosperity.

“Past prosperity,” he says, with a flick of his hand.

He harks back to a time when regulations were not so strict, and he could charge hefty recruitment fees.

“There’s too much competition now. Too many chalos.”

Narmi, Omo's wife, is a returning migrant herself. On the wall behind her are the things most important to her family: A photo of the Arab owner of the agency, the couple's photo and the official agent's certificate.

Omo Wijaya placement business was once thriving. A flood of sub-agents has made it more difficult for him now, he says.

Narmi, Omo's wife, is a returning migrant herself. On the wall behind her are the things most important to her family: A photo of the Arab owner of the agency, the couple's photo and the official agent's certificate.

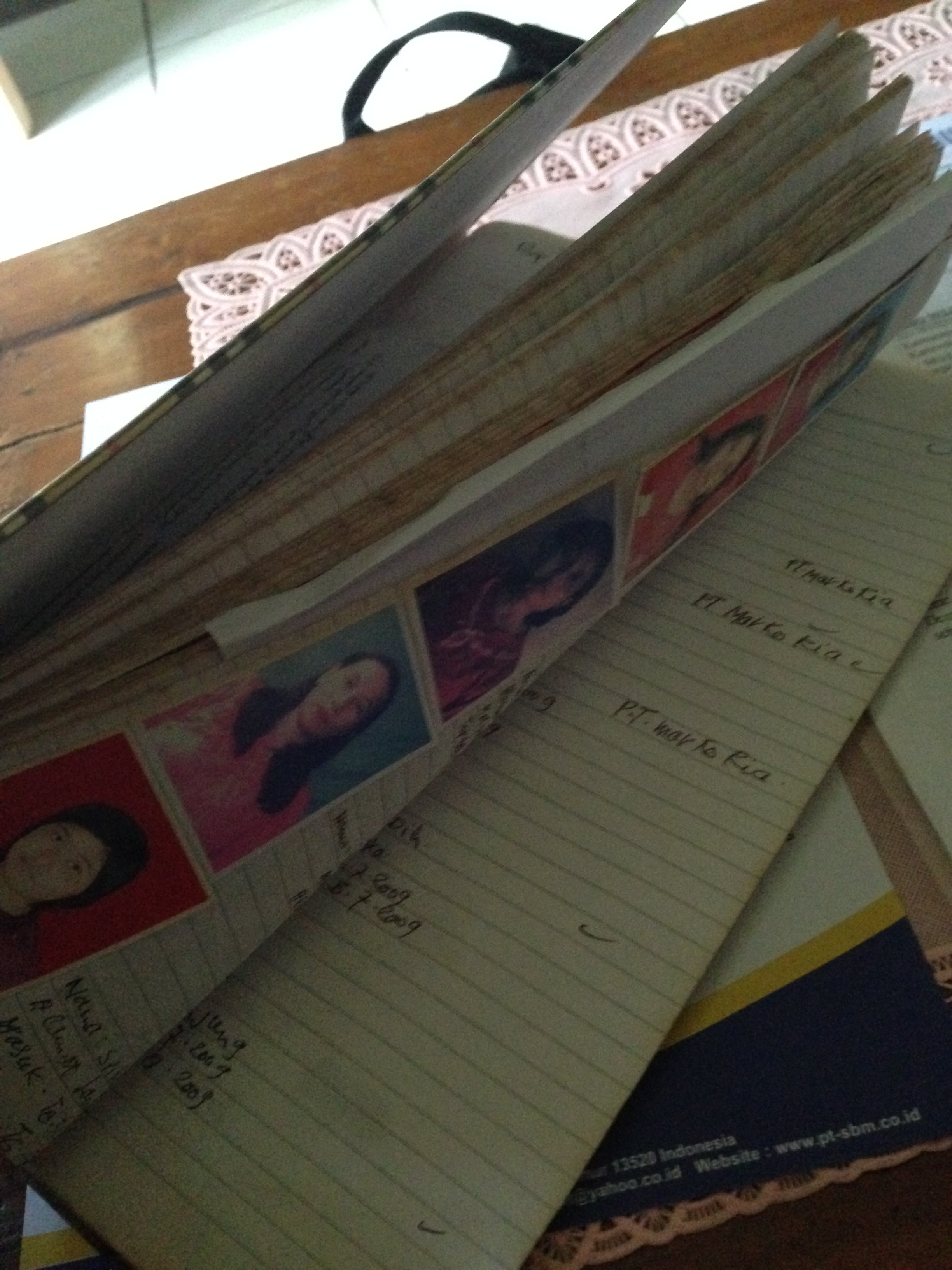

Omo brings out a register from a locked cupboard. Page after page of mug shots of women he helped migrate. There’s one page that looks like an account statement. Recorded neatly on that page is what Omo received from the families, and what was still due of families who chose to pay a percentage of the monthly salary instead of a lump sum. They often sold property or took loans at steep interests to pay for a job in the Middle East. This page of accounts ends abruptly, because in recent years the trend has changed.

[tweetable]Agents pay the family a fee – a signing fee – to lure the women into employment in the Gulf. Once the family takes the money, it’s as good as spent. Once that’s done, then the designated worker has little choice but to migrate.[/tweetable]Some workers we spoke to say this money is returned to the chalo over the period of employment. Some others say it’s a bonus that they don’t have to return. There are no set rules to the game; the goal is one: Get as many women, preferably young, to the Gulf to work as domestic workers.

The register, dog-eared and bloated with images and age, is proof of lives Omo has improved, his wife, Narmi, reminds us.

She is a returning migrant herself, and encourages young women to seek opportunities in the Gulf to better the lot of their families.

Her life has improved substantially; her children are married and settled into their own families.

Despite the level of comfort, Omo is not a happy man. He stares out into the large plantain leaves swishing in the rain, “no one wants to go to Arab (sic). The government doesn’t want anyone to go. And those who manage to, it’s all through the young chalos who don’t do it legally.”

Next: Recruited under duress, untrained and unprepared for migration