Stories of Origin is a series that explores the lived experiences of migrants and their families. This is the first of a three-part piece on migrant fishermen from southern India.

“It’s a village full of toothless and useless men,” Father Churchill says, only half joking. The former are the aged, and the latter are the children.

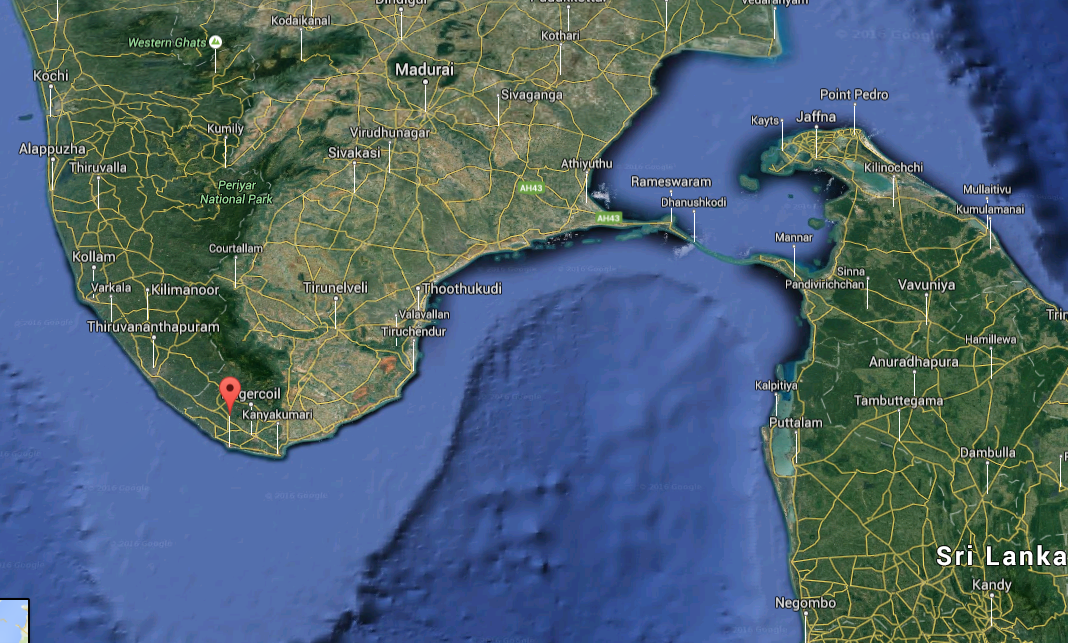

The picturesque coastal village of Muttom in India’s southernmost district Kanyakumari is unlike other fishing villages. No huts on the beach; no catamarans lining the shore; not even the smell of fish, just a salty breeze cutting through the humid summer days.

Concrete houses vie with each other to boast of successful forays the men have made to fish in the waters of Arabian and Persian Gulf. These are deep sea fishermen used to spending weeks away from shore. Neither their families nor they quite know if the sea gods will allow them safe return.

Father Churchill of the South Asian Fishermen Federation and his colleagues work closely with the community in this district, to both help those in distress and to empower those who remain.

A majority of the people in these areas have embraced Christianity, and juxtapose onto their new faith the superstitions and beliefs of their previous dogma. So the goddess who protects them while at sea and decides their fate is a Biblical figure in a white saree.

The houses are colourful with small doorways on narrow streets and large open windows facing the expansive Indian Ocean. The hospitality is overwhelming. Every home greets us with sugary tea and cakes.

“We can’t fear the sea; life or death, our fate is indelibly linked to the salt of the ocean,” Ritammal shrugs.

And that sea knows no boundary for her four sons in the Gulf, and the rest of the coastal families.

So while they fret and worry when their men are at sea, be it in the Indian Ocean or the Arabian sea, they know no other life, nor wish to seek another.

As you walk through the tiny fishing hamlets in the southernmost areas of India, it is hard to spot an able-bodied man. The few you see are either home on vacation or waiting to migrate.

It’s the women, children (the useless) and the aged (the toothless) who greet you, eager to share stories and photos of their menfolk, and allow you a peek into the relative prosperity remittances afford.

Deceptive affluence

So you see streets of affluent looking homes, many far grander than what the owner could actually afford. In debt, and drowning in multiple mortgages, the men keep returning to the harbours of the GCC.

The vagaries of the seas is the least of the migrant fishermen’s concerns. Rather, it’s being arrested by the coast guards of Iran or the GCC states. Over the last decade, thousands of fishermen have been detained and made to pay hefty penalties.

Yet, they are not deterred from migration.

In the last 13 years, Ritammal has seen four of her sons move to Saudi. Her house reflects it. On a corner plot of land stands a three-storeyed concrete house. Colourful, and furnished with every household luxury one could imagine.

[tweetable]“The pirates and the coast guards are both a problem,”[/tweetable] says Ritammal, echoing what others we interview say. They speak of the officials and the robbers as one. “We can be detained, robbed, or killed by any of them and no one will question it.”

Lissy’s husband Edward has been working in Saudi for the last 10 years, for the same sponsor. “The kafeel is a good man, but the risks are high at sea. The pirates come and take whatever they can from the boat, and sometimes even beat them up. But he hasn’t been arrested…” she pauses, “...yet.”

Ritammal’s youngest son is home from Saudi on vacation. He insists on not being named or photographed. “I have to go back to Dhahran and I don’t want my kafeel to get upset,” he murmurs.

“We are paid every two months, the kafeel gives us a share of our catch. This is not much. Some kafeels take up to 60%. And fish stock is dwindling. Trade has declined drastically.”

So, would it be better to stay behind in India?

His mother offers the reason, collectively for her sons and the rest of migrant workers in the fishing industry.

“The salt of the sea is our life. We can’t do work on the shore.”

Fish stock in the Indian coast has been dwindling for decades, and the state has not invested enough in protecting the trade or the fish workers (more on that in part 2).

"هيلينا" (يمين) و"شاجا" أكثر من جيران. زوجاهما صيّادان مهاجران، وهما لا تعرفان من يوم لآخر، ما هي الأخبار التي ستأتي من الشواطيء الأجنبية

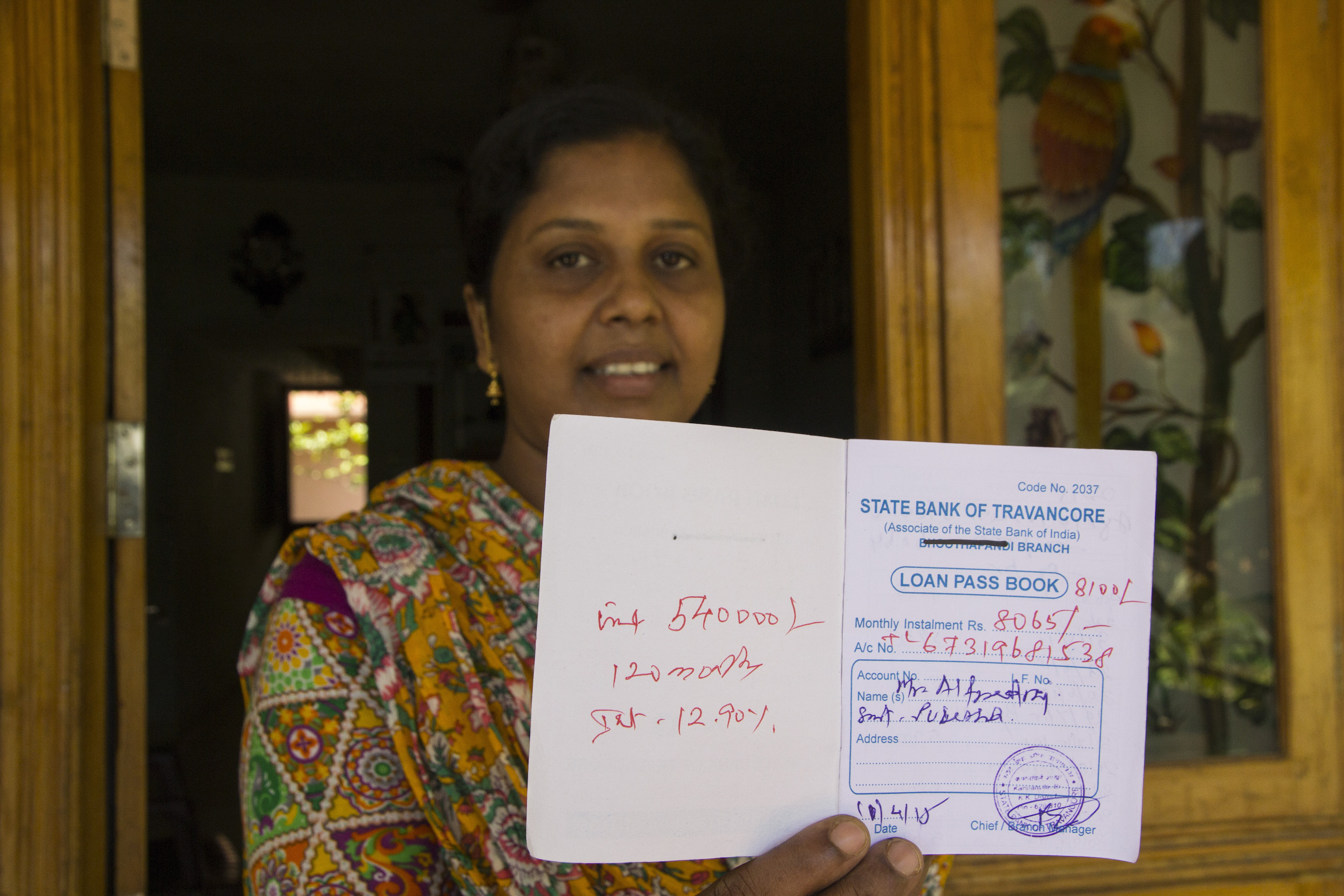

"We can’t quite manage. But banks will give a loan only based on their foreign employment, even if we would never earn enough to comfortably pay back," says Subeida. Her husband Seelan was arrested in Qatar.

Kadiapattinam is a village neighboring Muttom. There are 1500 households, all of whom have a family member in the Gulf. About 500 work in Qatar and the rest in Saudi. The few men you'd find are those who are old or the ones waiting to migrate.

Lissy’s husband Edward has been working in Saudi for the last 10 years. “The kafeel is a good man, but the risks are high at sea. The pirates come and take whatever they can from the boat, and sometimes even beat them up.”

“We can’t fear the sea; life or death, our fate is indelibly linked to the salt of the ocean,” Ritammal says. Her four sons all work in the Gulf.

As Father Churchill points out, there just aren’t enough landing centres. There is just the one private harbour in Muttom, where fishermen in mechanised boats bring in their catch and trade.

On the street that Ritammal lives, almost every house has someone working in the Gulf. So stories of hardship in foreign seas are common.

Vinoj for instance, has worked in Saudi Arabia for 15 years. “People do come and ask him for advise,” says his wife Bonslee. “They are aware of problems there… but always the hope that things will get better. Once you’ve decided then you can’t really stop.”

The ones who can’t make a living off the Indian coast may attempt shore work, according to the women we meet. But it’s not one that they are happy doing. ‘Shore work’ is a broad term for anything that’s not to do with the sea.

Arrests and detention

As we walk away from Ritammal’s house, Helena who is my guide for the day says the fishermen will go where there’s fish. Intrinsically they don’t recognise the borders. “They are all under great pressure to get a big catch, and hope every time that this once, the sea gods will help us get away.”

Rubin, Helena’s husband, went to Ajman in May 2015. A ‘captain’ in the village arranged for his visa. The captain is the one who recruits his crew here, usually from amongst his family and friends. The captain usually receives a ‘recruitment’ fee.

“He tried to fish here. We don’t have facilities for nets, for docking… it was a struggle. Nearly six months in a year there will be no work, and we go into debt. Rest of the time, they might make a profit of Rs 500 a week, sometimes Rs 2000. There’s no assurance.”

Rubin was amongst the 49 fishermen caught crossing waters from UAE to Iran.

From those 49, 8 fishermen were from Muttom alone.

Subeida receives us with a stack of papers. Home loan documents, her husband Seelan’s passport copy and her daughter’s mark sheets. On the day we meet, Seelan and his colleagues had just been released after being detained in Qatar for three months.

Seelan has been working in Saudi Arabia for 19 years. And this is not the first time he has been caught crossing borders.

“This time was different. They hadn’t crossed the border. The coast guards told them they just had some questions and urged them to cross. And then arrested them. They didn’t this time.”

She hazards a guess, “I think the guards who catch them get promotions.”

“The sponsor paid Saudi Riyal 5000 for each crew member as fine. Now they have to pay back the sponsor and can’t come back till then.”

The three months in Qatar and the next few months paying off the fine means the family goes deeper into debt. “My daughter is a very good student. She goes to an English-medium school. It’s time to pay school fees. And the house loan too… We can’t quite manage. But banks will give a loan only based on their foreign employment, even if we would never earn enough to comfortably pay back.”

Her voice is strong and belies the tears streaming down her cheeks.

[tweetable]It appears that at any given point of time, in this village alone, a family or two would be awaiting news of an arrested family member.[/tweetable]

Photography: Pattabi Raman

![Image relating to [Stories of Origin] High skills, low value: Indifferent Governments on both ends of migration](https://www.migrant-rights.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/harb2-1024x683-310x200.jpg)

![Image relating to [Stories of Origin] Life after arrests](https://www.migrant-rights.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/benj1-1024x683-1-310x200.jpg)

![Image relating to [Stories of Origin] Indian fishermen: Between the devil and the deep sea](https://www.migrant-rights.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Screen-Shot-2018-12-27-at-10.35.49-AM.png)