In the first of a four-part report from the Philippines, we spend time in two critical places where decisions are made. The offices of the overseas employment administration and recruitment agents. There's a very fine line that separates the two, in both tone and intent.

Short of a kidney, for a price, you can buy just about everything outside the POEA complex of offices. Smudge-proof ballpoint pens, waterproof passport covers, low-interest loans, water bottles and snack packs, photography and photocopy services, medical tests. The service providers are in a long queue that stretches from the gate all the way over the pedestrian overbridge branching out in five different directions. Closer to the gate, the Manila-esque queuing gives way to a dance of vendors, each politely edging the other out to briefly hold the prime spot right outside the gate, where no one can miss what’s being hawked.

And between the gate and the main door, a host of other services are available, for free, thanks to a steady flow of aspiring migrants and their families. Some offer, while others seek, help and advice. To fill out forms, to know more about Saudi Arabia, to pacify a worried brother that Dubai is not so bad, to exchange Facebook details and to assure a stricken young woman that the Philippines will indeed lift the Kuwait ban and she would be able to fly out soon.

There’s an air of camaraderie and in the minutes and hours they spend there, they self-organise into clusters – by the provinces they come from, the countries they are going to, the jobs they are undertaking, the returnees and the newbies.

The advice being shared, especially in the Saudi cluster, is not to go out even if you do get an off day. The off day is already seen as a privilege that only a few may receive. Facebook is the alternative to actual human interaction. Everyone sings paeans to the power of Facebook. The government, the agencies, the workers, the agents. It’s surreal, the power being bestowed officially and unofficially on an unsecured social media platform.

The POEA building looks like every government office in Asia, only a little bit more organised, and a lot more obvious in its purpose. The short flight of stairs leads to a lobby and a bank of elevators. Several counters line the wall – banks, insurance companies, financial services. In a small cordoned off area there’s a sales pitch in progress as two spirited youngsters have a group of aspiring migrants enthralled – the magic of remittances.

Becoming an OFW is a community initiative. It truly takes a village. And nowhere is that more obvious than in and around the POEA offices.

Not all of them are waiting to go abroad. There are quite a few who have come to file complaints – on their own behalf or that of a relative.

In search of justice

Laila has been waiting for a couple of hours. She and her cousin Felix have come to file a complaint and to rescue his sister in Saudi Arabia. This is their fourth visit (between January 15 and February 9) to the offices, and Felix had forgotten the dress code. While he has gone in search of suitable attire to cover up the sleeveless vest, Laila is killing time talking about Nona Fe to whoever is seated around her. She must have recounted the tale a dozen times, still not tiring of it.

Felix comes back, and then more details emerge.

Nona Fe went to work in Abha, Saudi Arabia on 31 December 2017. And from day one her problems started.

“The employer has been pulling her hair and pushing her around. She is overworked and given only one meal a day. They lock her up in the house and lock the refrigerator when they go out,” the brother pauses, looking ill at ease.

Laila chips in, “they don’t even allow her to use the toilet. They gave her a basin to do her business.”

There’s a whoosh of disapproval from the hangers-on who haven’t tired of hearing the story either.

Nona Fe is employed by a large family, with two adjoining homes, where she and another worker take care of everything.

In the initial weeks, she had no contact with her family. She secretly started using Facebook messenger on her Philippines cellphone. Her family pieced together her story over weeks of sporadic messaging. Felix shows the exchange on his phone. There are long gaps in communication. He is bewildered. Why would a human being be treated this way at all?

Felix and Laila first complained to the agency in Manila, who dismissed their concerns saying it was too soon, that she has to adjust and it will get better.

“We have paid for everything. How can we just let it go?” – An agent

Adjust or pay up

That’s the standard advice imparted to workers before they leave and while they are abroad. Nowhere is it reiterated more than at a recruitment agency.

In a side lane, adjacent to the offices of the Commission of Filipinos Overseas, is a narrow three-storeyed building. A signboard announces that this is Hopewell Overseas Recruitment Agency.

A hard-faced security guard demands identification before allowing entry. A few women are shooting the breeze, trying to draw the guard into a banter. The ground floor has a few chairs and a gated, locked stairwell inside which there are a few pieces of luggage.

Upstairs is a beehive. Several desks, tiny offices, walls plastered with job notices. Aspiring migrants, mainly women, are sprawled on metal chairs lining the corridors. The wait has been long it appears.

The agency goes headhunting for household workers in the provinces with permission from the PESO offices. Once recruited, the women are brought to Manila, housed in dormitories run by the agencies, and are given the requisite training.

In this office, the Kuwait ban is not yet seen as a dire situation. A recruiter says the problem is in Saudi. “They were dependent on us (Philippines) for the service sector. But due to nationalisation, those jobs are dwindling. It was the biggest market for us.”

Hazel, higher up in the agency pecking order, interrupts the casual conversation and moves it to the manager’s room, now empty of the occupant.

She is suspicious but answers the questions honestly enough.

She says homesickness is the main problem they have to deal with in the case of household workers. “We address it before they go. What’s the reason they are going? They should remember that. We also take the family’s help to convince the worker to continue working. We don’t consider regular complaints as a problem really if it’s solved. It’s a problem only if they file a formal complaint with the government office.”

And despite that, if the worker cancels, the family is asked to pay back the expenses incurred by the recruitment agency. “We have paid for everything. How can we just let it go?”

Exiting the building, the women are still outside, but this time in deep conversation with one another. There’s a new member in the group.

“She is supposed to go to Kuwait. We are all ex-abroad, we can go… but she doesn’t know what will happen. The agency will not do her paperwork for another country now.”

Marketplace for dreams

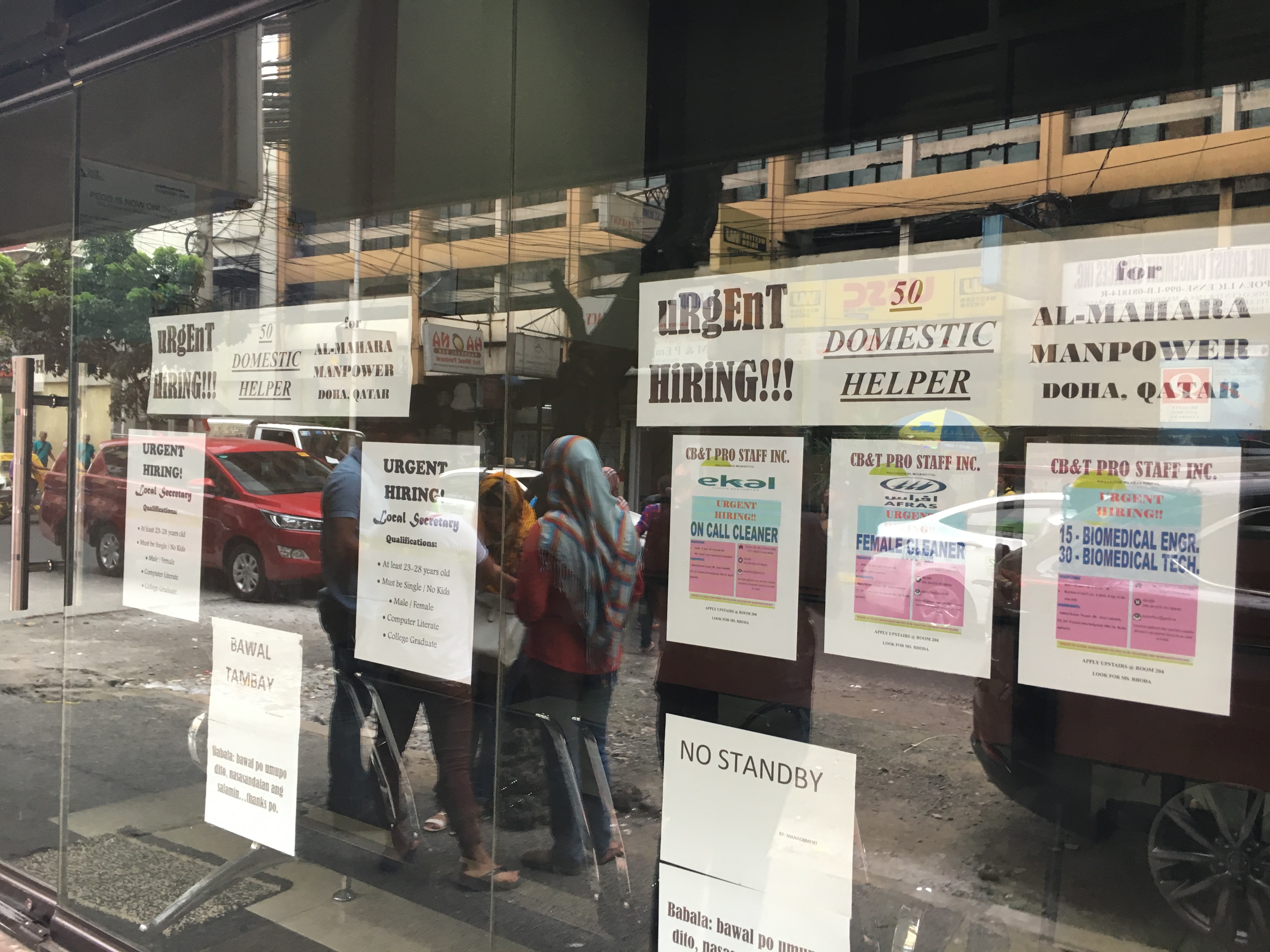

Honeywell is just a filament in a tangled network of recruitment. Not too far from here is the Mabini street, in Ermita. It’s a marketplace. Glass fronted offices with a mosaic of leaflets announcing jobs across the world. Many of these doorways are flanked by armed guards. Every job announcement is ‘Urgent’. There are more staff outside of the offices than inside. The trick is to lure potential migrants before a neighbouring agency can pin them to a contract. “Immediate visa. Free loan. Want to go to Dubai?” Promises fly around in Tagalog and other dialects.

Non-Filipinos are given a different sales pitch. “Po, how many workers you want? Maid? Sales?”

If you are not there to find a job, you must be there to offer some.

It’s just a couple of weeks since the Philippines banned its citizens from travelling to Kuwait for work. The environment in recruitment agencies, government office and training centres is fraught. What is to become of those who are one last paperwork away from migrating? There are close to 200,000 Filipinos working in Kuwait, which is a significant market.

Cecille, the interlocutor, is received with curiosity. She is done with agents. She is on the other side now. Helping returning migrants and their families, especially children, to find peace in an uncomfortable reality. Her chosen mode of healing is art. Her journey started 17 years ago when she was just 17. Her father, an OFW who returned from Saudi sank his tiny savings into drug dealing, and in the bargain, he and his wife became meth addicts. It befell on Cecille, the oldest, to become the caregiver.

“I went to Japan, to be an ‘entertainer’. You know what that means… trafficked, abused, battered… I am healing for and through my children, through my art.”

She walks past the agents, recounting her own journey, remarkably without malice or anger.