Campaign

Act against wage theft, ensure workers are not denied their dues

Over decades, millions of migrant workers have been denied all or part of their wages with little meaningful legal recourse. The Covid-19 pandemic has thrown this issue into sharp relief, with hundreds of thousands of migrant workers losing their employment. Many were unfairly terminated and refused their due wages and benefits. Some were stranded without income for months before they could return home to dire straits. Those with outstanding recruitment debts are pushed further into debt bondage, losing lives and livelihoods back home due to lack of income.

Long-term solutions to wage theft must recognise that the problem precedes the pandemic, which has only worsened violations and provided a deceptive rationale for unethical practices. Alongside structural reforms to labour migration practices, states must commit to holding erring employers accountable.

Overview

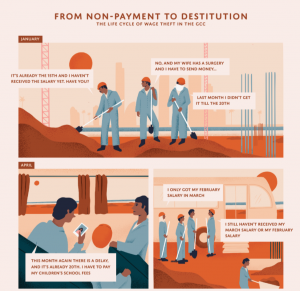

Of the various human rights violations that the Kafala system enables, wage theft is the most rampant. Poor complaints systems, constraints on job mobility, and weak Wage Protection Systems mean workers can spend months working without pay, and years trying to reclaim their due. The graphic below illustrates the lifecycle of wage theft in the GCC:

Workers who want to find alternate employment while pursuing their claims face a number of obstacles, including a lack of legal and financial support. Those who are forced to return without filing a complaint are especially likely to lose their dues. Some are duped or forced by their employers to sign documents forfeiting their owed wages in order to retrieve their passports or receive tickets home. Even those workers who have not signed away their rights still face an impossible battle fighting their cases from abroad as transnational justice mechanisms do not exist.

Domestic workers, particularly women migrants, are especially vulnerable to wage theft and have little or no recourse to lodge complaints. On average, live-in domestic workers work upwards of 70 hours a week, often but are rarely compensated for overtime. Even where domestic worker laws exist, protections are weak and these workers remain excluded from labour inspections and wage protection systems. Though all GCC countries – with the exception of Oman – stipulate end-of-service gratuity for domestic workers, most return without these entitlements.

Similarly, all GCC countries have laws that protect workers against arbitrary dismissals. Workers who are unjustly dismissed are eligible for compensation, but many workers do not pursue this claim because of lack of awareness of the law, time-bound restrictions to file a complaint, and the general difficulties of navigating the complaints system as a migrant.

The Covid-19 pandemic has introduced both more obstacles to justice and more opportunity for wage theft: employers have taken advantage of the turmoil to unfairly dismiss workers, repatriate them without their full dues, or otherwise renege on their obligations, even if businesses received government relief.

Workers who have returned prematurely and those still stranded in the Gulf have virtually no accessible means of claiming their dues. For domestic workers, the pandemic has further curtailed their freedom of movement and ensuing access to redress. Amid travel restrictions, many domestic workers were forced to stay at their employer’s home, even after completing their contracts and work for little to no wages.

Weak justice mechanisms

Access to justice across the GCC is weak even in the best of circumstances. Costly, time-intensive, difficult to navigate, and often not worth the outcome, the complaints system effectively discourages migrants from addressing their grievances. Though new mechanisms, such as virtual and fast-track courts, have been recently adopted in some of the Gulf states, both access to justice and enforcement of judgement remain key issues.

The pandemic has worsened an already faulty system in several ways: court delays for new or ongoing complaints have increased, which effectively means more expense for the worker. As resources and procedures move online, accessibility becomes even more of an issue for migrants. With embassies and community groups overextended in providing relief and repatriation to distressed workers, there are even fewer resources for migrant workers with complaints to rely on.

One urgent recourse that civil society organisations have advocated for since the outset of the pandemic is the establishment of a transnational justice mechanism for repatriated workers.

Reforms to the complaints systems, justice mechanisms, and labour policies are critical to addressing these issues beyond the pandemic. Key measures are noted below the case studies that follow.

Case studies

Saudi Arabia

Alumco’s full-time employees which include technicians and electricians were last paid their salaries in April 2019. Most have spent the last several months campaigning to get their dues.

Saeed, an Egyptian doctor, won his case at the Labour Court on 2 March 2020. His sponsor, however, appealed the verdict and soon after, Saudi suspended most government work due to Covid-19, including labour offices and courts. Ongoing labour disputes, such as Saeed’s, were put on hold. Filing new cases in person was out of the question, while, according to various workers, the online portal was down regularly during the pandemic. As of August 2020, the appeal court has still not assigned his case a date.

UAE

Nearly 500 workers of Emirates-based AMB-Hertel protested against months of non-payment in May. AMB-Hertel is an Emirati subsidiary of the French multinational Altrad.

Hundreds of Sobha Engineering and Contracting LLC employees owed months of unpaid dues are struggling for survival in the United Arab Emirates.

Bahrain

150 workers from Orlando construction company in Bahrain, victims of wage-theft, now contend with Covid-19 infections.

Several hundred workers of Fundament SPC owed up to 8 months of unpaid salaries and final settlement have been pushed into despair and struggle to survive in Bahrain.

Qatar

About 550 employees of a once successful Qatari company – Imperial Trading and Contracting Company (ITCC) – have been protesting non-payment of wages for over 11 months, which has pushed them and their families back home to destitution.

“I am starving since I don’t even have money for food. How will I pay back my loans if I don’t get my salary [through the legal process]? Sometimes I think suicide is my only option.”

Workers employed on a World Cup project in Qatar have not been paid for months, according to a recent report by Amnesty International. Salary delays began in early 2019, with many receiving no salary at all between September 2019 and March 2020.

What needs to be done?

Recommendations for Countries of Destination

Improve outreach information services for migrant workers, to increase awareness about of their rights and entitlements.

Include domestic workers in the WPS to better monitor their wage payments.

Labour inspectors must check that salary cards are in possession of workers and not with the company, as is often the case.

Ensure End-of-Service benefit payments are fool-proof, and they are provided either as encashable banker’s cheques or to the salary account of the employee.

Establish emergency funds to pay workers their dues. These can be collected later from the employer by the government.

Establish online complaint procedures, mobile courts, a speedy arbitration system and allow class-action suits.

Hold employers accountable through administrative, civil and criminal actions. Ensure judgements against employers are enforced without added cost and burden on migrant workers.

Strictly implement penalties so that victims of wage theft not only receive their due wages, but also compensation for hardships faced.

Support workers in giving power of attorney before they leave the country so that their claims for the statutory dues could be pursued in their absence.

In countries of origin where there are embassies of GCC states, establish a unit to handle wage theft cases of repatriated workers.

Set up sub-commissions at national level that look at the need for a reform of the justice system.

Include and pay special attention to migrant women and domestic workers in particular, in all such efforts.