Access to justice for migrant domestic workers in Lebanon: Q&A with ILO consultant Alix Nasri

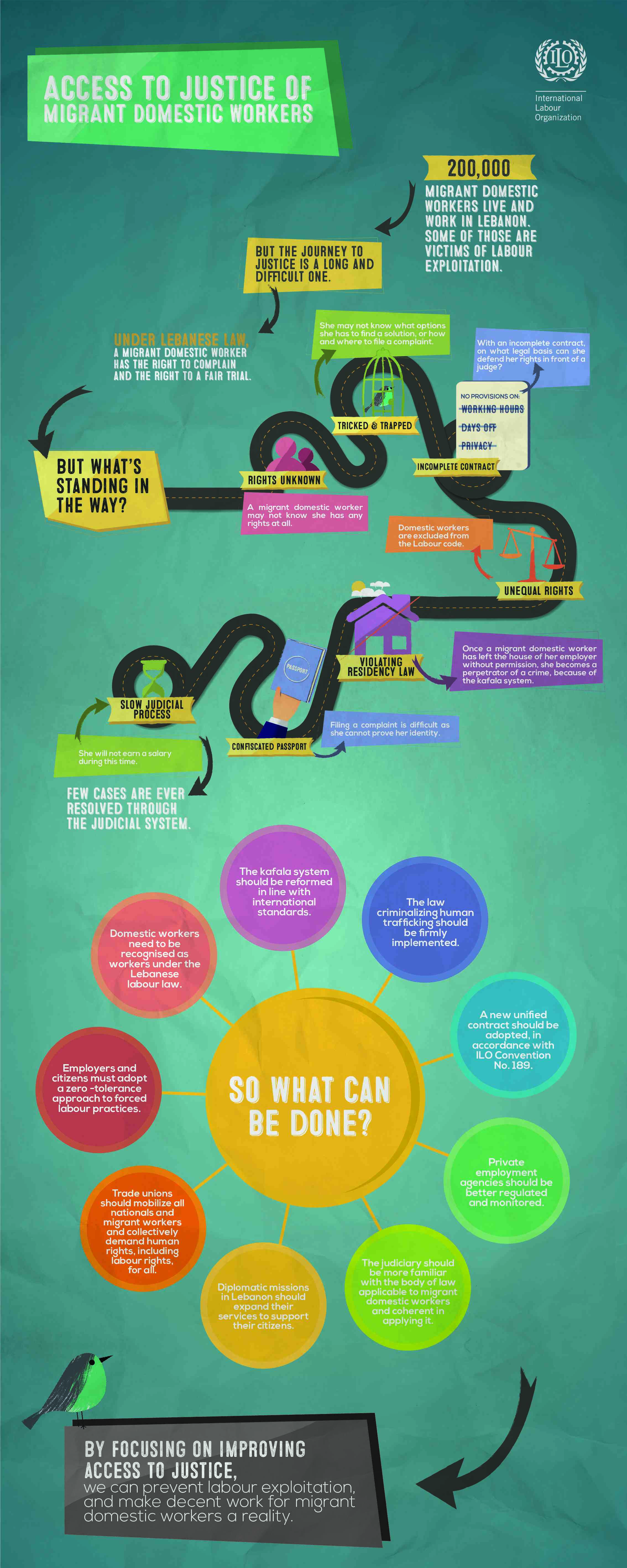

Reports of maltreatment of migrant domestic workers are all too common in Lebanon, yet only a few cases against exploitative employers and private employment agencies are brought and resolved in court each year. The ILO and Caritas Lebanon Migrant Center have teamed up to carry out research into why migrant domestic workers in the country are so unlikely to seek, and receive, justice.

The ILO/CLMC research study is the first in a series that the ILO will carry out this year on access to justice for migrant workers, and is based on the case files of 730 Ethiopian domestic workers who have been helped by CLMC in one way or another since 2007. It also analyses 24 cases brought before Criminal Courts and Labour Arbitration Councils by CLMC lawyers acting on behalf of migrant domestic workers from several nationalities.

Migrant-Rights.org spoke to Alix Nasri, one of the authors of the report, ahead of yesterday's launch.

Migrant-Rights.org: It seems that migrant domestic workers in Lebanon find themselves in a nightmarish double bind when it comes to seeking legal help for employment issues – and can actually find themselves criminalised for seeking help. Tell us more about the legal loopholes that migrant workers face in Lebanon.

Alix Nasri: A migrant worker who leaves her/his employer violates several provisions of the residency law in Lebanon. Unfortunately, the worker simply cannot just leave the exploitative employer, file a claim in court and then transfer to another job in Lebanon. The kafala system ties the worker to the employer. In a case of labour exploitation, the worker will be treated both as a criminal under the residency law for leaving his/her employer, and as a victim of abuse under the Penal code. This “duality” in treatment discourages migrant domestic workers from seeking justice and is a major obstacle in access to justice.

In addition, migrant workers are excluded from the Labour Code in Lebanon and the protection it affords other workers. This major protection gap should not prevent Civil Courts from litigating disputes arising from a work contract. Yet these contracts often do not contain key provisions, such as working hours, day off, and the right to privacy. As a result, lawyers file cases on behalf of migrant domestic workers that are only limited to disputes concerning the non-payment of salaries and the abusive termination of contract by the employer.

MR: Do employment contracts provide any kind of protection for migrant domestic workers?

AN: Even if a migrant domestic worker is excluded from the Labour Code, technically if there is a contract, he/she is entitled to the rights stipulated in the contract. But as mentioned previously the contracts often lack adequate provisions. As a result, lawyers from civil society organizations have rarely brought cases before the Labour Arbitral Tribunals for issues other than the non-payment of wages. Lawyers could make significant headway by filing cases on an array of different labour violations.

Another challenge is to prove that a migrant domestic worker was deceived about working and living conditions in Lebanon. This problem is compounded by the fact that some judges have decided that the contract signed in Lebanon in front of a notary overrides the terms and conditions that were stipulated in the initial contract, which the migrant worker agreed to prior to leaving his/her country. In order to file cases on deception of working and living conditions, lawyers will need to develop legal arguments as to why judges should use the more protective contract, even if it is signed the country of origin of the migrant worker.

MR: What kind of cases has CLMC brought to court on behalf of migrant workers?

AN: Caritas lawyers have brought both penal and civil cases in front of the courts.

Most of the cases that have reached the Labour Arbitral Tribunals are related to non-payment of wages. CLMC has already had some successes in this area, and has even won compensation on behalf of migrant workers who have already returned to their home countries.

Caritas has also won several penal cases related to physical abuses from the employer and retention of passport. So far there haven’t been any cases in which an employer has been prosecuted for human trafficking, even if the Lebanese law criminalizing human trafficking came into force in 2011.

MR: How do migrant domestic workers go about accessing legal help when they are in trouble?

AN: CLMC is the biggest service provider for migrant domestic workers, and has a physical presence at the retention center in Beirut where many migrant domestic worker who escape from their employer end up. As a result, CLMC sees new cases every day. Other civil society organizations and embassies of countries of origin are also providing legal advice and services.

MR: But are there any opportunities for migrant domestic workers to access legal assistance when they face problems with their employers before the situation reaches a crisis point (i.e before the migrant worker has ended up fleeing from the employer’s home)?

AN: It is worth pointing out that Lebanon has a very active civil society compared to other countries in the Middle East. They do a lot of outreach to migrant workers to inform them about their rights and where they can turn to for help. But in general, migrant domestic workers still lack awareness on the different remedies available to them in case of abuse or exploitation.

MR: One dynamic that you mention - which I find particularly shocking - is employers bringing false cases against migrant workers for petty offenses such as theft to court in a bid to intimidate them:

AN: Yes, this is a problem in Lebanon as it is in other countries in the region. Research by CLMC found that very few theft cases brought against migrant workers by their employers resulted in a ‘guilty’ conviction. There is a major abuse of the system by employers bringing cases against migrant domestic workers in ‘bad faith’. It’s an easy tactic used by the employer to control and intimidate the domestic worker. It would be important to challenge the judiciary on this in the future, and to advocate that those bringing false cases against migrant workers be punished for false accusations and bad faith.

MR: We’ve talked about legal loopholes that discourage migrant workers from accessing justice, but what about structural issues?

AN: One of the big, over-arching issue is the slowness of the Lebanese judicial system. Bringing a case to court can be an extremely lengthy process, which is off-putting for migrant domestic workers. Another major problem is the lack of capacity at the embassies of countries of origin for handling employment disputes. There is a heavy reliance in Lebanon on NGOs to provide support to migrant workers, but the embassies should also seek to strengthen their services. Also, the fact that migrant domestic workers have not been able to organize and collectively demand their rights has meant that access to justice is sought on an individual basis, case by case. These structural issues need to also be addressed in order to ensure decent work for migrant domestic workers in Lebanon.

You can read the full study in French here . Please check back here shortly for a link to English and Arabic versions of the study.