The Indian government has decided to allow Non-Resident Indians (NRI) to vote through e-postal ballots or proxy voting. Though NRIs were never formally disenfranchised, they had to be physically present to cast their vote with no option to cast their ballot remotely.

India has the single largest emigrant population. With over 14 million Indians living and working abroad, it’s ranked first amongst sending countries. Nearly half of them are based in the GCC.

According to PEW Research Centre:

The number of Indian-born people living outside of India and the number of Chinese-born people living outside China both doubled between 1990 and 2013 – for India, from 7 million to 14 million, and for China, from 4 million to 9 million. India has the largest number of people living outside of its borders, in 2013 surpassing Mexico, the former leader. (Russia and China rank third and fourth, respectively.) The United Arab Emirates (2.9 million) and the United States (2.1 million) have the most Indian migrants.

Whether Indian government’s decision will significantly improve policies governing its emigrants remains to be seen. Indian migrants, along with their counterparts from other South Asian countries, are amongst the most vulnerable and exploited groups of people in the GCC. The Indian missions in receiving countries are not equipped to redress the problems faced by their citizens.

Resident citizens of India who are poor do vote every five years without any long term benefit. In other words, mere franchise does not guarantee any right or growth for the poor in India.

Country of big numbers

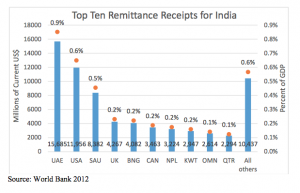

Statistics on India are always staggering: 543 Lok Sabha (central government) constituencies; 4120 state government constituencies spread over 29 states and 7 union territories; 814 million eligible voters; 14 million expatriates and close to $70 billion in remittances in 2013 alone.

The first set of numbers dilutes any power expatriates might have.

Let’s compare the Indian scenario to the Philippines, which passed the Overseas Absentee Voting Act in 2003, and is seen as a model of success when it comes to empowering migrants. Of its 100 million population, over 10 million (10%) are emigrants. Because it is a Unitary Presidential Constitutional Republic, where the head of state is directly elected, the Filipino diaspora have political clout.

India on the other hand is a Parliamentary Constitutional Republic, which means the numbers don’t translate into one solid front. The 14 million overseas Indians are scattered over hundreds of constituencies. While they might have more sway in a state like Kerala, which has a large and powerful emigrant population, the well-being of low income migrants hailing from other more populous states is up in the air.

The Indian government's recent decision to grant NRIs the right to absentee voting followed two separate petitions filed by a UAE-based doctor V.P.Shamsheer and a London-based NRI Nagendar Chindam.

“There are 10 million Indian citizens staying abroad, and with 543 Lok Sabha constituencies, this means an astonishing average of 18,000 votes per constituency may get polled from abroad. These additional votes, if polled, will obviously play a crucial role in state and general elections,” Chindam said in a statement earlier this week.

Aakash Jayaprakash, a human rights and migration specialist, speaking to Migrant-Rights.org before the decision was announced, also believed that including NRIs in the vote would cause a massive shift in how Indian politics function – especially with regards to how low income migrants are treated.

Aakash Jayaprakash, a human rights and migration specialist, speaking to Migrant-Rights.org before the decision was announced, also believed that including NRIs in the vote would cause a massive shift in how Indian politics function – especially with regards to how low income migrants are treated.

Indian daily The Hindu, writes: “The government’s decision to allow NRIs to vote could set the stage for expatriates to emerge as a decisive force in the country’s electoral politics.”

Not everyone shares this optimism. A former member of the Indian civil services told Migrant-Rights.org: “Resident citizens of India who are poor do vote every five years without any long term benefit. In other words, mere franchise does not guarantee any right or growth for the poor in India.

“Therefore, overseas Indians should not fall for this gimmick and instead focus on redressal of their most common and recurrent problems such as exploitation, especially in the Gulf region. Indian Missions in such countries must be given exclusive manpower and funds to address the problems of Indian expats in those countries.”

About half of Indian emigrants are headed to the GCC, of whom 70 percent are unskilled or semiskilled laborers. They are responsible for a bulk of the country’s 70-billion-dollar remittances. Remittances account for 3.7 percent of the country’s GDP, significantly larger than foreign direct investment (FDI) or official development assistance (ODA) ($24 billion and $3.2 billion in 2012 respectively).

Despite a large number of skilled migrant workers, almost half of India’s remittances come from the low and semi-skilled migrants. This same group remains the most voiceless both in the GCC and in India, but activists hope the ability to vote will empower them at home.