Fossil fuels and climate change: migrant workers take the heat

With the CEO of the UAE’s national oil company set to preside over the COP28 talks later this year, the Vital Signs partnership’s latest report lays bare how migrant workers in the Gulf are already experiencing the deadly effects of extreme temperatures

In recent months, extreme heat has been making the news, and it is not good news.

Deaths of workers from heat-related causes have been reported in Italy, the U.S. and South Korea. In India, 170 people were reported to have died due to heat-related illnesses in the states of Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. This year’s cases are just the tip of the (rapidly melting) iceberg. Researchers estimate that the 2022 European heatwave caused more than 61,000 deaths in total across the continent, while last year’s Lancet Countdown found that India had witnessed a 55% increase in deaths due to extreme heat between 2000-4 and 2017-21.

It is well established that fossil fuel extraction is the key driver of human-induced climate change which is leading to these conditions. Climate scientists have found that heat waves in large parts of South Asia have become 30 times more likely due to human-induced climate change.

If workers are dying due to climate crisis-induced temperature extremes in Europe, North America and Asia, what are the consequences for the millions of migrant workers in the Gulf, where extreme heat is already a regular occurrence, and is set to become even more frequent and severe over coming decades?

The Vital Signs partnership – a collaboration between London-based FairSquare and NGOs in South and Southeast Asia concerned about the health and mortality of migrants in the Gulf – examined this question in our recent report ‘Killer Heat’. The title of the report is not hyperbole. In the Gulf, very high temperatures aren’t recorded only during heat waves, but occur consistently for three to five months annually. Maximum daily temperatures top 40℃ between 100 and 150 days per year in most parts of the Gulf. By comparison, New Delhi experiences an average of 24 days with temperatures above 40℃. Chronic exposure to this level of heat can create cumulative stress on the human body, and risks exacerbating the impact of respiratory and cardiovascular diseases, diabetes and kidney disease. Rapid rises in heat gain can cause what the World Health Organisation describes as “a cascade of illnesses”, including heat cramps, heat exhaustion, hyperthermia and heat stroke.

Construction workers, who carry out strenuous work in areas exposed to the sun, very often wearing heavy personal protective equipment, are at particular risk of heat stress. Migrant labourers comprise about 90 percent of the UAE workforce and include approximately 500,000 construction workers. A 30-year-old electrician from India who worked on building projects in the UAE told Vital Signs that the heat was so intense, sweat would leak from his boots, while a 32-year-old plumber in Bahrain said he had trouble breathing in the summer months. A 31-year-old Indian electrician who used to lay underground cables in Saudi Arabia told us that, “ten minutes after the bus dropped us off at the work site, I felt like life was exiting my body”. Hailing from Bihar and being passed as medically fit during their recruitment, none of these men were strangers to heat before their migration, having worked in the Indian summer months. All of them described the conditions as unbearably hot in the Gulf, in interviews to Vital Signs researchers. Despite better earnings in the Gulf, one of them left his job for fear of life and returned to India.

Other migrant workers interviewed by Vital Signs researchers shared shocking testimonies of the long-term consequences of lengthy exposure to extreme heat in the course of outdoor work.

Ganesh, 30, from Nepal, went to the UAE in 2018 to work as a lifeguard and spent 12-hour shifts at the outdoor rooftop swimming pools of apartment blocks. “The ground was so hot I couldn’t touch it with bare feet,” he recalled. “It would burn my skin. You can’t imagine how hot it was.” After he returned to Nepal, Ganesh developed numerous health issues. Doctors diagnosed him with kidney failure, which he suspects resulted from substandard living conditions and abusive working practices in the UAE. A kidney transplant is unaffordable for Ganesh and his family, leaving him reliant on dialysis for the rest of his life.

None of the six Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) states have laws that adequately mitigate the risk posed to outdoor workers by its extremely harsh climate. Notwithstanding a new heat stress law in Qatar that slightly improves protections on what was there before, it remains the case that each government in the region imposes a rudimentary ban on work at certain hours of the day during the summer months. The striking lack of consistency between countries underscores the unscientific nature of these measures.

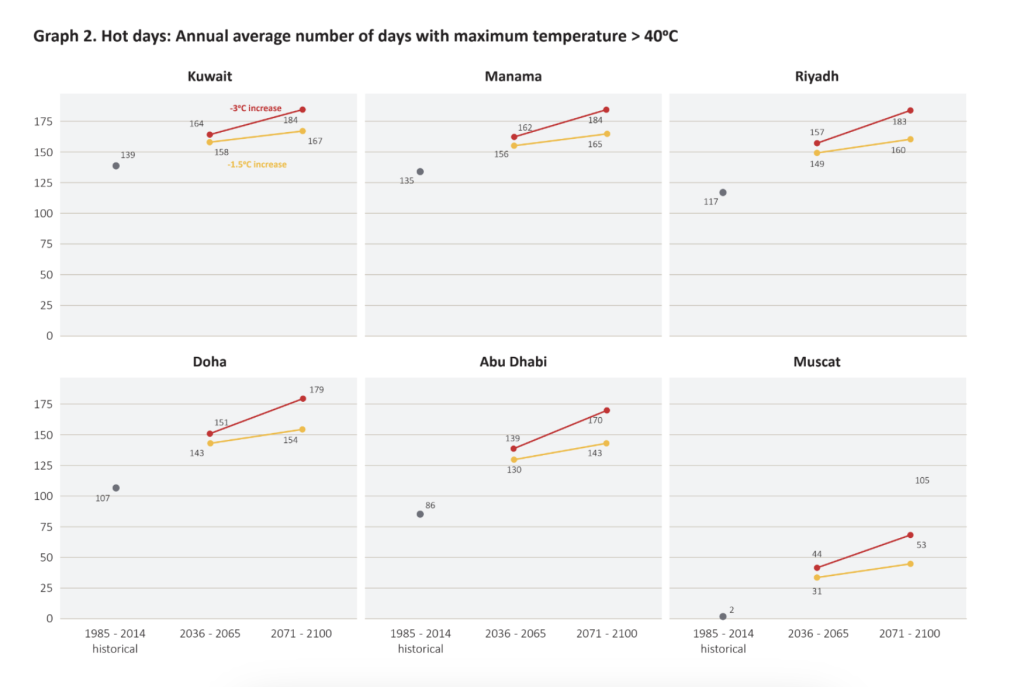

Vital Signs commissioned Barrak Alahmad of the Department of Environmental Health at Harvard University and Dominic Royé of the Foundation for Climate Research to analyse climate data from the Gulf, drawing on the latest state-of-the-art climate projection models. Their analysis is a brutal demonstration of how the climate crisis will intensify Gulf temperatures. If global temperatures rise by 1.5℃, the number of days in which air temperature in the UAE’s capital, Abu Dhabi, exceeds 40℃ will go up by 51% by 2050. Under a 3℃ scenario by the end of the century, the number of days at +40℃ will increase by an extraordinary 98%, while in Kuwait, Bahrain and Saudi Arabia temperatures will exceed 40℃ on 180 out of 365 days.

Alahmad told Vital Signs that even under more optimistic mitigation scenarios, the region is set to see a marked increase in heat-related deaths: “These conditions could seriously disrupt human societies in ways we are just beginning to understand”.

The UAE will this year host COP28, the global gathering of states to try to address the climate emergency. The irony is profound. The UAE, after all, offers the least protection of any Gulf state, banning work in extreme heat for just 232.5 hours in a year. Oman and Kuwait ban work from 1 June to 31 August from 11 a.m to 4 p.m., and 12.30 p.m to 3.30 p.m. respectively. In Saudi Arabia, the work ban operates from 12 p.m. to 3 pm from 15 June to 15 September, while in Bahrain restrictions do not begin until 1 July, when work is banned between 12 pm and 4 pm, until 31 August. UAE’s prohibited working hours amount to less than half of the hours banned in Qatar. In 2021, cleaners and security guards at the Dubai Expo centre, which will host the COP28 conference, told the Associated Press of 70-hour weeks in the withering sun. One Kenyan security guard told the AP: “Work, sleep, work, sleep. There’s no freedom… You just need to try to survive one day to another.” When the Expo 2020 opened in October, well after the end of the UAE’s summer working hours ban, tourists fainted from the heat.

As COP host, the UAE is under tremendous pressure, not least because it has appointed Sultan Ahmed Al-Jaber, head of its national oil company (ADNOC) as COP president, and because it has pledged an aggressive expansion of oil and gas production, 90% of which would have to remain in the ground to meet the net-zero scenario set out by the International Energy Agency. All of this, critics say, raises doubts about the credibility of the UAE state’s commitments to stop what the UN Secretary General has termed “global boiling”. When COP negotiators arrive in Dubai later this year, they will have further grounds for scepticism about whether their hosts are truly serious about tackling extreme heat, as they see workers toiling outside in conditions that – even in the relatively cooler month of November – they would likely not wish to venture into without the comfort of air conditioning.

Update 31 August 2023: Bahrain’s midday ban starts from the 1st of July and not 15 July, a correction is made to reflect this fact.