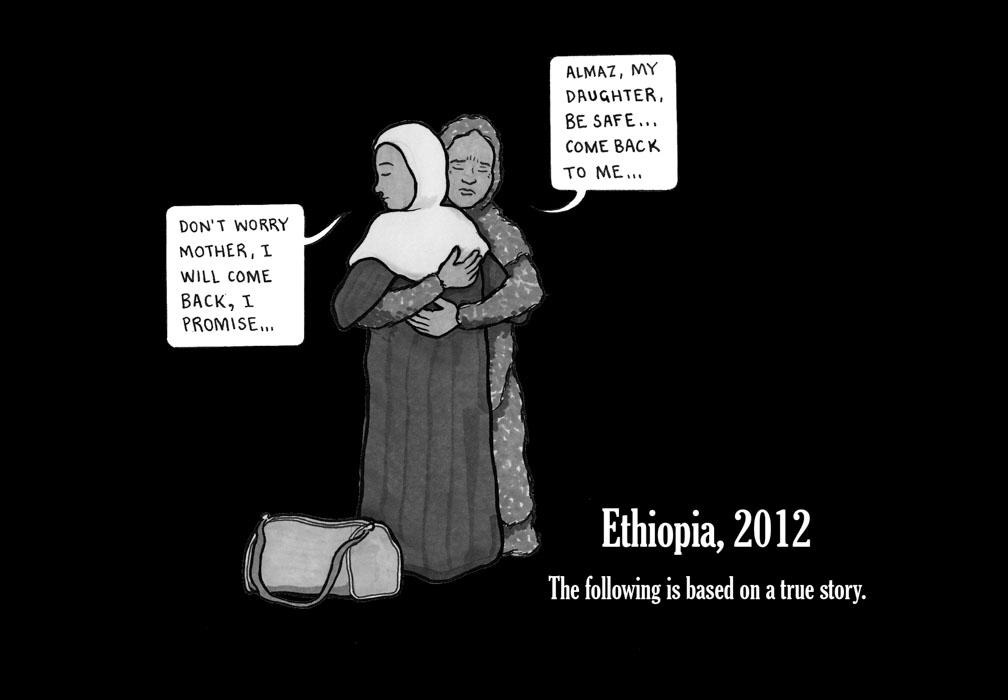

In “Almaz. A story of Migrant Labour” PositiveNegatives visualizes the real and all too common experiences of migrant domestic workers (MDW) in Saudi Arabia; based on the account of a former Ethiopian domestic worker. The main character, Almaz endures a spectrum of physical and emotional abuses that encapsulates MDW's isolation and vulnerability to malicious employers. The illustrations creatively and critically amplify the often invisible narratives of the millions of MDWs in Saudi and wider Gulf region.

The following essay featured on PositiveNegatives.org provides further context into the plight of domestic workers in the wider Gulf region:

The story visualized in 'Almaz' is that of thousands of domestic workers in Saudi Arabia and the wider Gulf region. Globally, domestic work is often an ‘invisible’ industry, taking place in the unregulated, private sphere of the home and subject to few labor protections.

As this comic strip illustrates, the vulnerability of domestic workers begins at home, with unscrupulous brokers and recruitment agents offering false promises of working conditions and wages while charging workers illegal placement fees. Some workers are very aware of the risks and trials compatriots have faced in the region, but the prospect of higher wages than could be found at home means they’re willing to take this risk.

The particular plight of domestic workers in Saudi Arabia and the wider Gulf region owes in part to the sponsorship or Kafala system, which renders workers disproportionately dependent on their employers. One common practice is for employers to confiscate identity documents and refuse to release workers from their contracts, leaving little choice for discontent workers but to escape. On July 5th of this year, a young African domestic worker committed suicide in a Saudi domestic workers’ shelter (read: detention center) after her sponsor refused to allow her to return home.

Other common working conditions include 10-hour+ working days with few breaks, no days off, confinement to the house, and delayed or unpaid wages. Domestic workers in Saudi Arabia work an average of 63.7 hours a week, the second highest rate in the world. Many domestic workers also suffer physical, verbal and sexual abuse from their employers and the employers’ extended family.

Though of course not all employers are abusive, domestic workers remain at the mercy of their employers’ kindness rather than protected by legislation. With the recent exception of Bahrain, domestic workers are excluded from national labor laws, instead they are only provided meager protection through patchy declarations, unequal bilateral agreements, and wanting unified contracts.

Many of these regulations suffer from poor enforcement due in part to an unwillingness to regulate the private sphere of the home – most domestic workers are required to live in their employers house, and are confined to the house even during their “free time”. Some workers also have restricted access to private communication, impeding their ability to seek help in case of distress.

Ethiopian domestic workers, particularly in Saudi Arabia and Kuwait face another layer of vulnerability; extreme racism. Though Ethiopian domestic workers were eagerly pursued by Saudi Arabia in 2012, following breakdowns in agreements with Asian countries accused of demanding unreasonable protections for their workers. Saudi authorities perceived Ethiopian and other African migrant-sending countries as pliable, publicly announcing it would begin recruiting workers from these countries to punish those that challenged them.

However, in July 2013, Saudi Arabia imposed a ban on the recruitment of Ethiopian domestic workers and 40,000 visas for Ethiopian migrant workers were cancelled, and a moratorium levied until a “study on the threat” of Ethiopian workers is completed. The move was accompanied by an almost fanatically xenophobic discourse that depicted Ethiopians as heartless, cruel, and criminal dregs of society. This discourse, perpetuated by the authorities, the media, and the public, inflamed the late 2013 crackdown on ‘irregular’ workers, which led to the deportation of over 100,000 Ethiopian migrants.

The comic strip below explores the trajectory that far too many domestic workers endure, depicting the systematic lack of protection for workers throughout the recruitment and migration cycle. This story amplifies the hundreds of stories silenced and the experiences of countless workers made invisible.