A popular Malayalam television program now seeks to use its reach in GCC and India to help migrant workers and their families.

Sivasankaran Pillai was reported missing in Saudi Arabia in 1979. His family in Kerala still have no information of his whereabouts. Radhama Rajappan went missing in Qatar in 1988, and to this day no one knows of her whereabouts. These are some of the cold cases that span several decades.

Hundreds of such stories are the subject of Pravasalokam, a popular Malayalam TV show. In the last 15 years, the program has tracked and found 900 missing persons across the GCC. Most of the referrals are from families living in Kerala.

Rafeek Ravuther, the producer of the show, feels not successful enough.

“Just 900 out of more than 2000 cases we have reported on. A large number are still missing; And it is difficult to not give the family a concrete answer.”

Stories of people gone missing is expressed in popular films and books, including the one Migrant-Rights wrote about, Goat Days.

For Ravuther, it was a series of personal experiences that inspired him, along with his colleagues, to launch Pravasalokam.

“Many of us living in Kerala are directly or indirectly linked to migrants in the Gulf migrants. One of my uncles was stranded in Bombay (now Mumbai) for a long time, waiting for his Gulf visa to come through. My grandma in Cochin was always waiting for him, every night, with supper.”

Many like him disappear into a vacuum of waiting and disappointment. But it was something more drastic that was the catalyst.

“A cousin of mine, who was a civil engineer, committed suicide just two days after joining duty in Muscat. Another cousin who was in a cattle feed factory in Ajman, UAE was missing for four months. Despite my brother working in Gulf Today daily, we could not locate him. I knew there would be hundreds of similar cases elsewhere. These incidents occurred just as I was joining Kairali TV in July 2000, and my program head asked me to do a Program for Migrants.”

“A cousin of mine, who was a civil engineer, committed suicide just two days after joining duty in Muscat. Another cousin who was in a cattle feed factory in Ajman, UAE was missing for four months. Despite my brother working in Gulf Today daily, we could not locate him. I knew there would be hundreds of similar cases elsewhere. These incidents occurred just as I was joining Kairali TV in July 2000, and my program head asked me to do a Program for Migrants.”

The majority of the migrants who go missing are blue collar workers and domestic workers. “Most of them, we find out, were in house arrest conditions, without access to communicate with home. Then, there are also people who ‘run away’ from sponsors, become undocumented and end up in a 'no job-no income' state; they are reluctant to communicate with their family. There are also some who change countries, become alcoholics or have extramarital relationships, and choose to stay incommunicado.”

CIMS

There are 5,687,032 (2012, Ministry of Overseas Indian affairs) Indians living in the GCC. They make up the single largest group of foreign workers in the region. Kerala traditionally has been the primary sending state in India.

Pravasalokam taps into this large diaspora, uses a network of journalists, social workers and the viewers themselves, to track and trace missing persons. Over the years Pravasalokam has evolved into more than just a missing person’s report on television. “With the help of philanthropic viewers, the program is also paying for the education of many missing persons’ children, including those of a housemaid who was later found to have been dead for years in a Gulf country,” says Ravuther.

The team also realised that finding a missing person, or when it’s a cold case, informing a bereaved family, didn’t provide closure.

They realised there was a critical need for financial aid for orphaned families, education support for the children, and assistance to those still stranded; and along side that a campaign to educate migrants and their families, and prevent the dire cases the TV program deals with. Hence, the establishment of Centre for Indian Migrant Studies (CIMS) of which Ravuther is the director. This centre now hopes to provide valuable services for migrants in distress, including financial support and awareness campaigns.

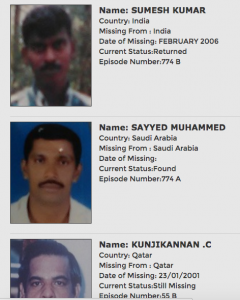

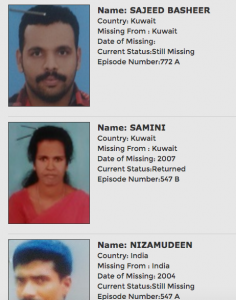

Their website also provides a list of migrant workers who are still missing. Migrant-Rights.org urges citizens and residents in the Gulf countries to have a look at the list, and see how you can help trace the missing.