In early February Qatar’s cabinet approved a draft law on domestic workers, though very little information accompanied the announcement. But a few more details have been revealed in a report submitted to the ILO Governing body. The report will be taken up in the ongoing 329th session in Geneva.

The provisions of the law barely skim the surface of the problem.

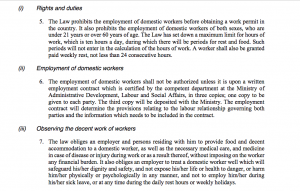

A draft law in 2008 met with several hurdles, particularly over the provision for a weekly off day. The new law includes a weekly 24 hour day of rest. It does not specify how and where the domestic worker will spend it, or about his/her freedom of mobility.

Quite clearly, the Qatari cabinet rushed the law’s approval on February 8, to be able to add it as ‘progress made’ in time for its response to the ILO on February 20. The ILO had initially set March 2017 as the deadline to determine if it would appoint Commission of Inquiry. Following Qatar’s report, there is a request to defer the decision to November 2017, the final decision on which would be taken on 21 March.

Qatar said: “Legislators ensured that the law is in conformity with the provisions of the Domestic Workers Convention, 2011 (No. 189), which relates to the decent work of domestic workers.”

A closer reading of the provisions of the law show that this is not necessarily true.

On a positive note:

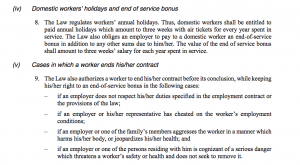

- The law does specify three weeks of annual paid leave, including airline tickets paid by the employer

- Workers are eligible for end of service bonus – three weeks pay for every year of employment

- Even before the law was approved by the cabinet, Qatar had made mandatory that all employment contracts be certified by the Ministry of Administrative Development, Labour and Social Affairs. A total of 42,905 recruitment contracts for migrant domestic workers were certified

However, other details are sketchy at best, with some very glaring oversights and gaps:

- No minimum wage has been stipulated

- The law doesn’t specifically include DWs in the Wage Protection System, though this might be assumed if they come under the purview of the Ministry of Labour

- While employers are responsible for decent accommodation and medical care, there are no specifics on how this will be monitored

- Dispute settlement are subject to the provisions of Law No 14 of 2004 and amendments thereto, including the recently constituted workers’ dispute resolution committees. While this appears on paper as inclusive, it fails to recognise the great isolation in which domestic work is carried out, and that there is no effective inspection mechanism.

The law also doesn’t address the problem of ‘runaways’ or ‘absconding’.

The moment a worker in distress leaves their employer, they can be reported as such, rendering their status illegal in the country. Unless there’s a specific provision addressing this, workers would hesitate to leave an abusive work environment, leave alone file a complaint.

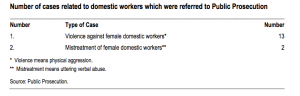

This probably explains the very low number of cases reported to public prosecution. The report mentions only two cases of mistreatment of female domestic workers and 13 cases of violence against female domestic workers, during an unspecified period of time

This probably explains the very low number of cases reported to public prosecution. The report mentions only two cases of mistreatment of female domestic workers and 13 cases of violence against female domestic workers, during an unspecified period of time

When the law comes into force, Qatar would be only the second country in the Gulf, after Kuwait, to have a domestic workers law. It should ensure that it is not merely ticking off a box to deflect attention, but making changes that truly empower and protect domestic workers.

Qatar should learn from the stumblings in Kuwait’s experience, where few of the progressive provisions in the domestic worker’s law have been implemented in the year since its passage.

Editor's note: The decision to defer to November 2017 is not yet final. The text has been edited to reflect this.