In the second series of reports from Uttar Pradesh, India, we look at the high dependence on unlicensed agents and the 'hundi' network, despite the rather obvious perils.

In village after village, home after home, it’s the same story; a community of shared distress and deja vu; and no one fighting back or holding accountable the agents who are painted in shades of black and grey.

Noor Allam went to Jeddah when he was just 19, in 2005. He went on an Umrah visa and stayed on irregularly for four years.

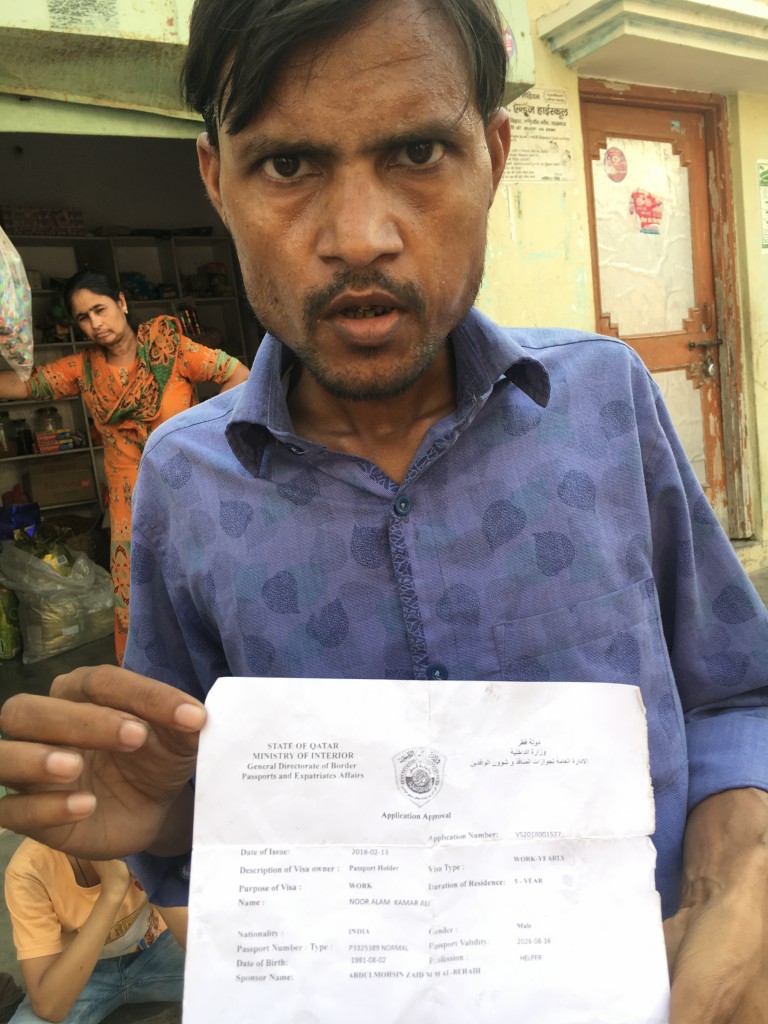

“Now I want to go to Qatar. I have paid 40,000 to Asif (the agent) already, and now have to pay another 45,000.” – Noor Allam

“I was doing zari work for a Yemeni’s workshop… he said he was Saudi. I got 1200 riyals and the work hours was long. I would have stayed on but got caught by the police and I am now blacklisted.”

He tried going to Dubai, again irregularly, and his passport was damaged.

“Now I want to go to Qatar,” he says, holding up his entry visa. He didn’t have much time at that point to pay the agent the final amount. “I have paid 40,000 to Asif (the agent) already, and now have to pay another 45,000.”

Noor, like the rest of the people we speak to, has little awareness of what the regular migration process looks like or any interest in finding out more about it, as they don’t trust the government or the system.

The reason, in theory at least, is that a neighbour or relative who is an ‘agent’ can be held more accountable than an office in a strange town. Even if the agent often takes no responsibility. Like when Abdul Wahabi’s brother Mohammed Tayif returned from Mecca after three months, having endured severe hardships without food or money. The agent, 150,000 rupees richer thanks to Tayif, shrugged it away saying, “It’s your kismet, what can I do.”

Tayif was supposed to do zari work in a home business, but ended up doing household work for an abusive kafeel, and fought to come back. Now he has a five-year ban slapped on him, and his wife has lost all the jewellery pledged to raise recruitment fees.

The stories, repetitive; the hardships, uniform.

They refuse to believe that you can migrate without getting into debt. Justifiably so… while on paper that’s a possibility, the sheer size of the country, the extreme poverty of the state they come from, and the marginalisation (both forced and self-inflicted) makes it impossible to navigate the system without falling prey to false promises and fraudulent agents.

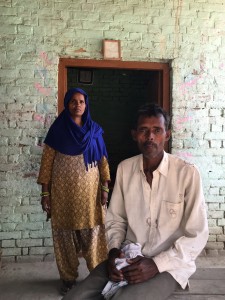

Buddhu and Amina have four sons. Sacks of onions and other fresh produce are stacked up on one side of the verandah that leads to their home. The family buys vegetables wholesale from the nearest town and retail it in their small village. It’s barely enough to make ends meet.

They still managed to muster more than Rs200,000 to send one son to Dubai and the other to Kuwait. Both earning less than expected and the latter subject to abuse and ill-treatment by the ‘madam’ of the house where he works as a driver.

Yet, there are no two ways about where the sons would rather work. “Everyone in the ‘mohalla’ (community) goes to Dubai or Jeddah.”

As we sit on the raised verandah of Amina’s home, many from the ‘mohalla’ drop in to offer their stories.

The storytelling is abruptly interrupted as a young man from the neighbourhood walks up to Amina’s home and demands an identity card. “Anyone can print a business card. How do we know who you are? How can we trust you?”

We could well be the government poking its nose where it doesn’t belong, he insinuates, adding as an afterthought, ‘or an agent’.

Nisar’s mother had borrowed money from neighbours to send him abroad and is overwhelmed with the laundry list of problems in front of her.

Amina apologetically offers the ‘best sweets from Mumbai’ to make up for what she saw as an inhospitable interruption.

A short drive from there, in Gadi village, Nisar Alam and his mother are trying to make a plan for their future. The 21-year-old went to Ras Al Khaimah with the promise of a job in a juice shop.

His mother is beside herself. “I paid Rs85,000. He was supposed to make more (money)… pay that back, get his sisters married”

Nisar says he did know till he reached the Lucknow airport that he was going to the UAE on a tourist visa. Taju, the agent, had shared no information with him until that point.

“There was one more person with me at the airport. Same story. When we reached Ras Al Khaimah we were kept in a room. The agent took everything from us.”

“Even the sweets I sent him… it went bad,” the mother chips in.

Nisar and the other person shared a room with Taju’s brother and his friends. “Taju’s brother works there. He was supposed to find a job. And we had to pay for all our food. I only had 100dhs with me. I would get one roti and eat it over two days.”

The family fought with the agent and made sure he paid for Nisar’s ticket back, and he returned in less than a month. The rest of the money, according to Taju, went into expenses and cannot be returned.

Nisar’s mother had borrowed money from neighbours and is overwhelmed with the laundry list of problems in front of her. “I have to pay them back. I have to get two daughters married. And Nisar… what will happen to him?”

“The hundi-wallahs (brokers) work out of small rooms all over the country (Saudi). All day, every day, they just sit there collecting money from people working there.”

In defence of the ‘agent’

She is inconsolable, and her neighbours see it. Yet, another thirty or so went to the UAE with Taju’s ‘help’ in the last few months – all on tourist visas and with the promise of a non-existent job.

Buddhu and Amina have four sons, two of whom are in the Gulf. The family had to raise over Rs200,000 that they could ill-afford

Many were now being returned.

Taju’s phone number is on everyone’s contact list.

A quick call and a quicker dismissal of the problem follows.

“I have nothing to do with all this. Alika Travels (in Lucknow) gives visa and contract, I only help those I know well. I don’t make money. He (Nisar) didn’t want to work. It’s not my problem. My brother also went on a tourist visa nearly two years ago, and he is employed and makes money. He does zari work. Nisar could have worked, he didn’t want to,” Taju says, over a phone call. “I paid for my brother too. 70,000. How else can you go abroad? These people…”

Mohammed Imran has some sympathy for Taju and his likes.

Imran lives is Seepahiya village, and has a brick home and runs a small grocery store. Relative affluence in an otherwise decrepit street.

“You can’t blame the agent. Everyone knows very well how they are going, what visa… it’s common knowledge. Agents are not ‘cheating’.”

According to him, when someone doesn’t like the job or are frightened in the new place, they say the agent cheated.

“He (the agent) takes money because that is his business. You go because you want to earn more money and you know the risks. There’s one guy here (in his village) complaining about being a shepherd. But that’s his visa, no? I met so many in Saudi too, who came like this.”

Shan E Ilahi agrees with some of this argument. There are close to 300 unregistered agents in UP alone, he estimates.

Shan runs a travel agency in a crowded market, in the heart of Lucknow. His office is tucked away behind a row of shops selling colourful, embroidered suits and sarees. He used to send workers regularly to Saudi and UAE, but now is waiting for registration of his business as per new regulations. Meanwhile, he provides travel services for tourism and pilgrimage.

“A local candidate will trust a local agent. Even if they are unlicensed. I am paying a lot to be registered, still, the workers will go through those middlemen who mislead them. The workers going from UP are all unskilled and uneducated.”

This is probably why even those who eventually reach out to a registered agent have to go through an illegal one. And probably why the government-run UP Financial Corporation, which also does overseas recruitment, has not to date made a single placement.

Shan is entrenched in both the community that migrates and the network that helps migration. And now, he is the person a cheated returnee or potential migrant goes to.

On his desk is a tall pile of folders. Cases he has helped register at various police stations, seeking justice for those taken for a ride by the rogue agents.

This doesn’t make him particularly popular, as it disrupts an established business model, so cases are filed against him as well. “None of which has been proven,” his father, a thus-far silent observer, says proudly.

The dirty underbelly

The irregular migration process demands the cunning and ingenuity of many.

“You can’t blame the agent. Everyone knows very well how they are going, what visa… it’s common knowledge.” – Mohammed Imran

Saudi now is clamping down on those who overstay the Hajj and Umrah visa, and the agent is blacklisted. A new obstacle means a new innovation in smuggling and trafficking.

Shan explains what’s common knowledge in the market. Those with an ECR passport cannot exit the country without going through the due process.

“But here’s the catch, the visa has to be stamped by the Saudi embassy here, but the employer doesn’t have to attest the contract with the Indian embassy. So there are chemicals that are used to remove this visa carefully, and workers are sent to Dubai on a tourist visa. In Dubai, the Saudi visa is stuck back on the passport.”

At every step, there’s a possibility for exposure and penalisation. Of the worker, not the agent.

Imran is something of an expert on the irregular migration process. He lays bare the workings of the migration underbelly, especially in Saudi, where the sheer size of the country allows people to hide in plain sight of the law.

He went to Saudi in 2011 on a tourist visa. “Fully aware… the free visa was too expensive, and this was only Rs65,000. Tailoring and embroidery workshops are really popular in Saudi, so I found a job and stayed for 22 months. I wanted to go and stay as long as possible. When they announced the amnesty in 2013, I came back.”

The first year he was an unpaid apprentice, with food and lodging covered. “The following year, I could earn even 1200 riyals a month if there were good orders. There’s an Indian businessman from Sitapur who runs his empire there in Saudi. The kafeel had visas that he distributed to smaller businesses. In the unit I worked in there were 20 of us. Not even one on a proper visa. None of us was paid monthly salary. We could get 50 riyals one day, 200 another, and nothing at all some days.”

The ‘Hundi’

Because of the haphazard payments and the lack of documents, the workers were all dependent on the ‘hundi’ or ‘hawala’ system. A hugely popular way of moving money, especially in the South Asian communities, and one that the government pushes back hard against.

There are no official currency conversion rates, promissory notes, or receipts, just trust and fervent prayers.

“When I had enough riyals I would go to a broker. He will say this amounts to 20,000 or 30,000 rupees and that’s all… They would say the day after we will give it to your family in Bareti or Seepahiya or whatever the village is. We will call our family. And as promised someone will be at the doorstep, with the money, on the promised day.”

Imran’s thinks he might have sent 100000 or 115000 but is not sure how much he lost in conversion and fees.

“The hundi-wallahs (brokers) work out of small rooms all over the country (Saudi). All day, every day, they just sit there collecting money from people working there. He has a network all over Uttar Pradesh too.”

Most of those who use this service may be undocumented workers. But there are also those whose families may be illiterate, don’t know how to go to Western Union or a bank, and feel this is simpler.

“Everyone knows about the hundi there, just as they know about all the illegal workers in the sweatshops. An open secret that officials turn a blind eye to.”

When the amnesty was announced Imran escaped from his room and surrendered.

His post-migration plans did not pan out, and he wants to go back.

“Agent says if I have a high school certificate then I can get an ECNR (Emigration Check Not Required) passport. Easier to go then. I will wait and go the proper way. Other people’s experience does not matter. You have to be hit bad and experience all that yourself before you change your methods.”

Previous: Migration in the times of distrust

Next: Building Trust: Two steps forward, one step back