Forced evictions: Kuwait’s dehumanising campaign targets male migrants

Across the Gulf, discriminatory campaigns target low-income male migrant workers living in shared dwellings. In Kuwait, the recent “Be Assured” campaign has left hundreds of low-income male migrants homeless and in miserable conditions.

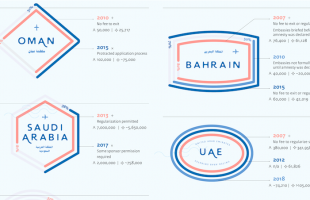

(image source: nabd.com)

Kuwait’s “Be Assured” campaign is the government’s latest concerted effort to marginalise lower-income migrant workers. The campaign, which ran from July 1 2019 until the end of August, evicted unaccompanied male migrant workers – often erroneously referred to as “bachelors” – from residential neighbourhoods. Authorities also shut off water and electricity to force workers out of accommodations.

The Kuwaiti government installed 124 billboards across the country to promote the campaign and encourage nationals to use a dedicated hotline to report ‘bachelors’ in residential areas.

According to the Kuwait Municipality’s public relations department, authorities evicted unaccompanied migrant workers from 119 houses and cut off electricity from 120 homes in July. In August, unaccompanied migrant workers living in 175 homes were evicted and electricity was cut off in 144 properties. By the campaign’s end, authorities issued warnings to more than 500 properties for violations.

Evicted workers were not provided with any housing alternatives, and little consideration has been given to their plight.

Migrant-rights.org spoke to two migrant workers affected by the eviction campaign. Shakil and Fazal, from the Indian state of Jammu and Kashmir respectively, had lived alongside 50 other workers in a three-story building in Jleeb Al-Shuyoukh, a neighbourhood densely populated by labourers, for the past five years.

Shakal, Fazal, and the 50 other migrants are now homeless.

Shakil and Fazal told MR that they were unaware of the reason for their eviction; all they knew was that the ministry came and disconnected the electricity without notice. They called the Kuwaiti owner of the building, who told them the electricity would be restored shortly, as soon as he paid a fine. It’s now been over two weeks.

Life for the men has been miserable since they’ve been forced from their homes. They are currently staying with acquaintances and friends nearby.

Discriminatory policies fuel further discrimination

The "Be Assured" campaign and Kuwait's ongoing efforts to remove "bachelors" from residential areas ignores the fact that low-income migrant workers often have little choice but to live in shared dwellings, given the lack of affordable housing options in the country. Under the labour law, only employers working for government contracts and those employing workers in remote areas are required to provide adequate accommodation and transportation services. Employers who do not provide suitable accommodation must pay workers an allowance in lieu, according to Kuwait's Ministerial Decision number 199 of 2010. This allowance must equal at least 25% of the worker’s wages if they are paid the minimum wage, or 15% of worker’s wages if they are paid more.

Kuwait’s private sector minimum wage is set at KD75 (~ USD250) per month. Minimum wage workers are therefore provided KD18.75 (~USD60) to rent a place. Consequently, the only housing options affordable and practically available to them are these packed rooms in “bachelor” accommodations. Workers whose employers do not provide any housing stipend at all face even more challenges in finding a place to live.

These high living costs and low wages also make it difficult for lower-income migrant workers to bring their families to Kuwait, and the minimum wage required to sponsor family visas make it impossible. Contradicting its efforts to reduce the “bachelor” population, Kuwait doubled the minimum wage requirement between 2016 and 2019. Only migrants who earn KD500 (USD1650) per month can sponsor their wives or children.

Migrants constitute 70% of Kuwait’s total population, and 70% of migrants are male. Yet, their long history in the country and their majority participation in the economy has not translated into an open, inclusive society; the Kafala system’s politics of exclusion, along with spatial segregation policies, has instead created hostility and friction, and many citizens do not want to live next to low-income migrants.

Many migrant workers live in remote labour camps or in temporary housing near project sites. In the city, however, male migrants often live in shared dwellings. This practice emerged over the past few decades as the migrant population grew, and as Kuwaiti nationals moved out of the city proper and rented out their old houses to migrant workers.

More recently, renting out informal, shared migrant accommodation has become a lucrative business for Kuwaitis, as only nationals are allowed to own property. These accommodations include buildings constructed specifically to rent out to migrants, properties developed during the 2000s boom, as well as old, converted houses. Some landlords partition rooms to fit more migrants and maximise their profits. While initially these rentals were concentrated in Jleeb Al-Shuyoukh and Khaitan, they have expanded to other residential areas such as Fahaheel, Sabahiya, Andalusia, Salmiya and Dasma.

In her study of Kuwait’s urban transformation and social relations, Farah Al-Nakib notes “After 1950, affluence, suburbanisation, functional zoning, the privatisation of public space, and the lack of people’s participation in the making of their spatial surroundings all contributed to the erosion of Kuwait’s historic diversity. The country’s demographic diversity remained and in fact increased, but interactions between people of different backgrounds became restricted under new conditions of social exclusion and spatial segregation”.

In 1992, Kuwait enacted Law No. 125, which prohibits “bachelors” from living in residential areas and ordered any such residents to leave within six months. However, the law has been poorly implemented primarily due to bureaucratic overlap, with several different government institutions responsible for its enforcement.

Furthermore, the sanctity of private property in Kuwait is legally entrenched; authorities cannot enter a building without the owner’s permission except in special circumstances. Consequently, properties illegally rented to migrant workers often were not inspected.

Authorities also simply lacked the will to enforce the law, because rentals generated profit for nationals.

But with an increase in complaints from citizens over the past few years, Kuwait established “The Committee for Minimising Bachelors Living in Private Residential Areas” to address “the phenomenon” of low-income male migrants who are unaccompanied by their families.

As a result, Kuwaiti authorities have more strictly implemented Law No. 125, and have also proposed a number of additional measures to reduce the presence of unaccompanied migrant workers in residential areas.

Planned labour cities in the country's margins

Kuwait plans to build six labour cities in the distant urban periphery to house “bachelor” workers who will be removed from residential areas in ongoing efforts. The labour cities will be distributed across the country’s six governorates, with the first planned for South Jahra, and will accommodate 20,000 to 40,000 migrant workers. The cities are a public-private initiative, and construction is expected to start by the end of 2019.

Accommodation that is affordable, decent, and well-regulated is critical, but location is also important; the planned cities are far from city centres, distancing migrants not only from their workplaces, but also from the government offices, embassies, and community groups they rely on in times of distress.

During the 2016 eviction campaign, one Arab migrant told Al Hurra news: "if you provide a decent alternative, a place that is connected well, that for example takes you 30 minutes to get to work, we would go there." Another Asian migrant said, "My work place is close, my accommodation is close, why take me far away? this is really a problem.”

The forced segregation of low-income migrant workers also further marginalises them from society; migrants are being removed from “residential areas” though they are indeed residents, not merely workers.

Indifferent and lazy media reports feed into racism

The issue of “bachelors” in Kuwait reemerges in public discourse and media alongside anxieties about “demographic imbalance”. Local media reports on the “Be Assured” campaign mostly lack any perspective from the affected migrant workers, instead parroting the dehumanising and racist remarks made by authorities.

Commenting on the Jleeb Al-Shuyoukh area, Kuwait’s Municipal Council member and head of Ahmadi governorate committee, Fuhaid Al-Muwaizri, told Kuwait Times that “the area is considered a haven for lawbreakers and residency violators, and has piles of trash, insects and rodents, with an absence of health and educational awareness among its Asian communities.”

Earlier this year, Kuwait’s Arab Times ran an article headlined “Exodus of Expat families, more bachelors gives rise to ‘sexual harassment’ against kids”, which blames the increase of child sexual abuse on migrant men who live alone, despite there being no publicly available evidence to support this claim.

Local and migrant families may have some legitimate concerns with male-dominated communities, but racist, stereotypical rhetoric does not invite just solutions. The issue of migrant labour accommodation is much more complex and deserves a constructive discussion on the safety and quality of housing, the importance of family reunification, and the contribution of migrants.

Rhetoric in Kuwait today stands in sharp contrast with its past cosmopolitan port city culture; authorities fuel discord with discriminatory remarks and discriminatory policies, ruthlessly betraying the migrants who make-up the majority of their workforce. Kuwait has an obligation to ensure migrants have access to suitable living conditions and enjoy freedom from discrimination.