Dropping Dead

Qatar’s death certificates for migrant workers are a template for denial

|

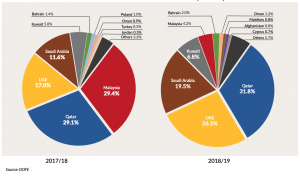

Roughly 230,000 Nepali migrant workers headed to the GCC states in 2018/19 alone, with the majority concentrated in Qatar, the UAE, and Saudi. Qatar was the top destination for Nepali migrant workers, employing roughly 30% of all incoming Nepali workers abroad in the same period. This report focuses on Qatar for reasons of access, and it is critical to underscore that Nepal’s 2020 Labour Report indicates that high rates of unexplained deaths have occurred in several destination countries, and most notably in Saudi Arabia. |

“This will be my last time working in this country,” Sukram Tharu said to his wife Rita on a video call from Qatar on a Friday night in April 2020. Before going to bed, he promised, “I will return home after a year and stay with you.”

But his promise will never be realised. Later that night, Sukram had suddenly complained of sharp pain in his chest. His fellow workers immediately called an ambulance, but it was already too late. He took his last breath in a cramped room in one of the wealthiest countries on earth – Qatar.

Qatar’s Public Health Department attributed his death to “acute heart failure due to natural causes.” But his wife is befuddled by his strange demise. “Just a few hours earlier, I saw him totally fine,” Rita said. “I don’t understand what happened to him. How could he die that way?”

To her knowledge, Sukram, 35, had no health ailments. Nor was he taking any medication. He was medically “fit” and did not have heart disease either, according to his pre-departure medical examination report.

After the death of the family’s sole breadwinner, their 13-year-old son dropped out of school. He began working as a labourer in his hometown in the Bardiya district of Nepal.

“Our other two – a daughter and a younger son – go to primary school, but I have trouble providing for them as I have no money,” said Rita, struggling to maintain her composure. “We had a dream of staying together in our newly built home. But he will never come back,” she added, with a choke in her voice.

Despite working in Qatar for more than six years, Sukram’s wife has not received any compensation from the employer. Nor has she received clarity as to the actual cause of Sukram’s death, as no post-mortem was conducted.

And it’s not only Sukram’s death that is mired in doubt.

CASE STUDIES |

|

An increasing number of Nepali migrant workers’ deaths in Qatar, and other destination countries have gone unexplained in recent years, with both Nepal and destination governments neglecting to ascertain the underlying causes.

Based on the deceased workers’ medical records, employment contracts, photographs, travel documents, and the testimonies from victims’ families, Migrant-Rights.org’s investigation reveals a grim picture of untimely and unexplained deaths. The deaths of young, medically “fit” migrant workers, often raise no questions, are categorised as ‘natural causes,’ and cases are closed without attempts to understand the causes to prevent similar deaths.

The documents MR reviewed indicate that Qatar’s Public Health Department issued death certificates without carrying out any investigations to identify the real cause of death, even though these workers were in their 20s and 30s and certified healthy, in mandatory pre-departure tests, at the time of migration.

Notification of deaths is also a haphazard process, with neither the employer nor the embassy efficient, or the first, in contacting next of kin. Instead, when workers who otherwise speak to their families almost daily cease communication for a few days the families then call the co-workers to enquire — and that phone call is often how they find out about the passing of a loved one.

Between 2008 and 2019, a total of at least 1,095 Nepali migrant workers died in Qatar, which is nearly one-third of the total deaths that occurred across the Gulf countries, according to Nepal’s Foreign Employment Board, the government entity responsible for the welfare of migrant workers.

“The actual figure of workers’ deaths must be at least higher than they reported because it only incorporates the deaths of workers whose families received compensation,” said Yubraj Nepal, a co-founder of the Center for Migration and International Relations (CMIR), a non-profit organisation established by returnee migrant workers. “And the Board’s data excludes the deaths of undocumented workers because they cannot apply for the compensation as per Nepali law.”

CASE STUDIES |

|

The Nepali Embassy in Qatar that tracks all deaths did not provide the data but did respond via email to MR that they were currently processing the repatriation of three bodies.

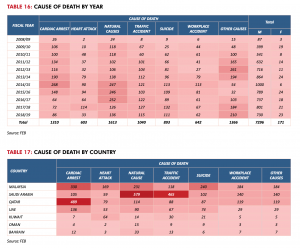

Although the figures shared by different organisations on workers’ deaths vary slightly, they all indicate that the majority died of “cardiac arrest,” “heart failure,” and “natural cause” – terms that describe the “terminal event” or manner of death but do not specify the underlying cause.

In a recent report, Amnesty International accused Qatari authorities of having “failed to properly investigate” workers’ deaths, thereby making it difficult to determine the underlying causes of deaths, and “precluding any assessment of whether they are work-related.”

“For medical professionals, what triggers cardiac arrest or heart failure is important,” said Dr Megnath Dhimal, the senior research officer at the Nepal Health Research Council (NHRC). “Saying ‘due to natural causes’ literally doesn’t mean anything.”

In Qatar’s case, it could be related to working conditions, or it could even be a result of extreme heat stress as labourers work in high temperatures without drinking enough water, he added.

Some of the workers themselves had reported heat stress at their workplace before they died. Sukram, who worked on oil rig maintenance in Qatar, often told his wife that he had to work in the blazing heat. “He would say that his job was difficult, but he had to do it as he had no alternative,” Rita said.

Gangaram Mandal, 34, from the Saptari district of south-eastern Nepal, also worked under the scorching sun at a construction site. In July 2020, he died in his sleep. The death certificate, predictably, states “heart failure [due to] natural cause,” but his family members suspect he was worked to death.

“His health was excellent, and he had never taken any medicine related to the heart,” according to Laduwati Devi Mandal, Gangraram’s wife. “But I know he would work throughout the day in Qatar, no matter if it was sweltering hot.”

A 2019 International Labor Organisation (ILO) report has also found that migrant labourers working outdoors in Qatar are exposed to “high” or “extreme” heat stress levels. The study revealed that one-third of the workers interviewed experienced dehydration and hyperthermia at some point.

CASE STUDIES |

|

‘Cardiac arrest’: Number one cause

Over a phone conversation just a day before his death, Mohammad Salauddin, 24, told his wife that he was planning to return home soon. His wife Madina Khatun recounted her last talk with her husband, sitting on the porch of a shabby wooden house in the Saptari district of Nepal.

“He seemed very excited, hoping to meet his daughter for the first time. But now it will never happen,” she looked at the only photo of her husband on her mobile, tears streamed down her cheeks.

Salauddin’s death left Madina a widow at 22, with a two-year-old daughter who has never met her father and a predatory debt that she has no idea how to pay off. “It’s our misfortune that he won’t be with us anymore,” said Khatun, who lived with him only for six months.

With no source of income at home, Salauddin had gone to Qatar with the hope of earning a decent salary, leaving behind his pregnant wife. In August 2018, he began working as a cleaning labourer. Three years later, he died. The death certificate states “Cardiac arrest” as the cause of death. This is difficult for the family to accept.

“He had never reported any health issues, never fallen sick. He was strongly built and young. I don’t think he could die of a heart problem,” said Salauddin’s mother Nunu Khatun, sobbing.

Among the documents that Salauddin’s family received along with his corpse, there is no post-mortem report.

Nepal’s Foreign Employment Act is silent on the investigation of Nepalis’ death abroad, while Nepal’s Criminal Procedure Code does not clearly describe whether its provisions regarding post-mortem apply to migrant worker cases. Nepal’s existing laws lack clarity over how to conduct post-mortem or autopsy, or any investigation whatsoever into deaths of migrant workers abroad. The Code states, in case of homicide, suicide and unusual situations, the investigation authority shall immediately go to the place where the corpse is located, examine the corpse, and send it to a doctor for postmortem.

“However, to my knowledge, there is no example of conducting an autopsy of the migrant workers in Nepal who died abroad,” said Anurag Devkota, a human rights advocate who works at Law and Policy Forum for Social Justice.

“Cardiac arrest” was the leading cause of death reported among Nepali migrant workers in Qatar between 2008 and 2019, accounting for 45% (489 workers) of total Nepali deaths in the country, according to Nepal’s Labor Migration Report. In 2019, a study by a group of climatologists and cardiologists examined the link between Nepali workers deaths and heat exposure in Qatar. They concluded that heatstroke was a likely cause of cardiovascular fatalities.

And though ‘cardiac arrests’ occurring in accommodation comprise a significant percentage of worker deaths, these are not classified as workplace fatalities and therefore are neither investigated nor compensated. However, Article 3 of the ILO’s Violence and Harassment Convention (C190) redefines the workplace to include “places where the worker is paid, takes a rest break or a meal, or uses sanitary, washing and changing facilities” and “employer-provided accommodation.” Still, the recently released ILO report on occupational injuries in Qatar (see box below) does not include these deaths in its analysis.

Mohammad Salauddin’s wife Madina Khatun (left), two-year-old daughter (middle) and mother Nunu Khatun (right)

Mohammad Salauddin’s wife Madina Khatun holds up a photo of her deceased husband. His mother, Nunu Khatun (right)

Gangaram Mandal’s daughter Baby Kumari, 19, with father’s photo frame and his younger daughter Pratima Kumari (green t-shirt) and wife Laduwati Devi Mandal.

Mohammad Salauddin’s wife Madina Khatun (left), two-year-old daughter (middle) and mother Nunu Khatun (right)

Neither compensation nor communication

While bereaved families in Nepal are struggling to survive in the absence of breadwinners, the reluctance of Qatari authorities to investigate deaths also deflects from their responsibility to pay compensation.

When deaths are attributed to ‘natural causes’ or otherwise deemed unrelated to work, employers in Qatar are not obliged to pay compensation, said Barun Ghimire, a human rights lawyer and the program manager of the Law and Policy Forum for Social Justice, an organisation that works on migrant rights issues.

Nor are they obliged to conduct post-mortems in the case of ‘natural deaths,’ unless the death is related to crime (see sidebar on autopsy laws). The refusal to pay compensation has dire consequences.

For example, despite losing his life in 2021 working in a foreign land, the family of Rajlal Pasman, 40, has not received any compensation yet. Rajlal’s wife Palki Devi received just NPR 312,000 (US$2,605) from Qatar after her husband’s demise, but it was only his unpaid salary and end of service benefits.

“He was the only one employed in the family of five,” said Gaya Pasman, brother of Rajlal. “Now, how can she repay the (NPR350,000) loan and continue her children’s education? How can she fund her daughters’ wedding?”

Palki Devi heard that she could claim compensation. But she hesitated to try as someone told her there is a lengthy and cumbersome bureaucratic procedure that one has to go through.

Most often, the victims’ families are illiterate, and from remote villages. They simply do not know the procedures and are unable to prepare the paperwork, said Barun.

“Bringing the dead body to the home itself is a big deal for them. Who cares about their compensation?”

If any worker who has migrated abroad dies for any reason during the contract period, or no later than one year of the end of contract, the closest heir to the deceased may receive NPR 700,000 (US$5,900) from the government upon the examination of the application, according to the Foreign Employment Rules of Nepal.

But the family of Rajendra Prasad Mandal, 47, received no compensation – neither from Qatar nor in Nepal. “I don’t know why we didn’t get money,” said Rajendra’s son Ramsagar. “We don’t know what we need to do. No one helped us.”

And for the families of undocumented workers, getting compensation is only a dream.

They are not entitled to any financial assistance from the government because the Foreign Employment Act does not recognise those who go abroad via unofficial channels or those with expired work permits. And the Foreign Employment Rules are silent as to how to compensate their families.

“This creates troubles for the ones who reached abroad in pursuit of foreign employment via unofficial routes,” said Yubraj Nepal of the Center for Migration and International Relations. “Whether documented or undocumented, they have contributed to the nation through remittances, but the law discriminates against them.”

The families say they were not informed about the deaths of their loved ones in a timely manner, let alone able to receive compensation in a straightforward way. None interviewed during this reporting were informed of their kin’s death by the employer or Nepali embassy.

“I heard about my brother’s death only after five days when his friend called us,” said Gaya Pasman, brother to Rajlal, whose body was brought back to Nepal nearly three weeks after his death. (Repatriations normally take four to five days, according to the FEB, unless further investigation is required due to a murder or other crime).

With both information and repatriation of the body often delayed, the family's pain compounds. Family members usually get information from fellow workers or the media, instead of via any official channels, said Barun.

“The bereaved family has the right to know about the deaths immediately, and their body must return at earliest, but there is no proper chain of communication.”

Turning a deaf ear

Last year, the Supreme Court of Nepal issued a mandamus order requiring the Ministry of Labor, Employment, and Social Security to conduct a compulsory post-mortem of the migrant workers whose deaths were categorised as “sudden” or “natural.”

The court also asked Nepali state agencies – the Ministry of Labour, Department of Foreign Employment, and Foreign Employment Promotion Board – to abide by the provisions of the law regarding the minimisation of the risk of migrant workers’ death and their insurance, compensation, health examination, and pre-departure orientation, and repatriation.

“Even after the court order, things have not changed.” confessed lawyer Barun. “Young and healthy migrant workers continued to die and be abused.”

Note: Four of the seven companies mentioned in the case studies were contacted on their publicly available emails for comments. No response was received. There was no contact information for the other three.

12/16/2021: This post was updated to reflect legislative changes.

ILO’s Qatar OSH report: Gaps in data collection identified, but no concrete measures on prevention of deathsA report released by ILO Qatar Office in November 2021, drawing on data from the recently established Unified Registry for Workplace Injury Prevention in Qatar (WURQ), maintained that it was “currently not possible to safely present a categorical figure on the number of occupational injuries and fatalities” in the country. Data for 2020 reveal that 50 fatalities were attributed to occupational injuries, and that there were 506 severe occupational injuries, with an average of 42.2 severe injuries per month. Severe occupational injuries were most commonly caused by falls, followed by road traffic injuries, falling objects and machinery. WURQ reports that of the 50 deaths, 30 occurred pre-hospital (60%), and 20 occurred in hospital (40%). Most fatalities resulted from falls and road traffic injuries, and most occurred in the worksite. The ILO’s definition of occupational injury is: “any personal injury, disease or death resulting from an occupational accident”; and an occupational accident as an “unanticipated and unplanned occurrence[s] including acts of violence resulting from and in connection with work which cause one or more workers to incur a personal injury, disease or death”. According to Qatar’s Labour Law No. 14 of 2004 occupational injuries are: “…accident happening to the worker during the performance of his [or her] work or by reason thereof or during the period of commuting to and from his [or her] workplace, provided that there is no stoppage, lagging behind, or deviation from the normal route of commuting to and from the workplace.” |