With one death every day, Saudi Arabia holds the dubious distinction of having the highest mortality rates amongst Nepali workers. With the lack of investigation into the underlying causes of death and stark indifference of authorities, there seems to be little hope for change.

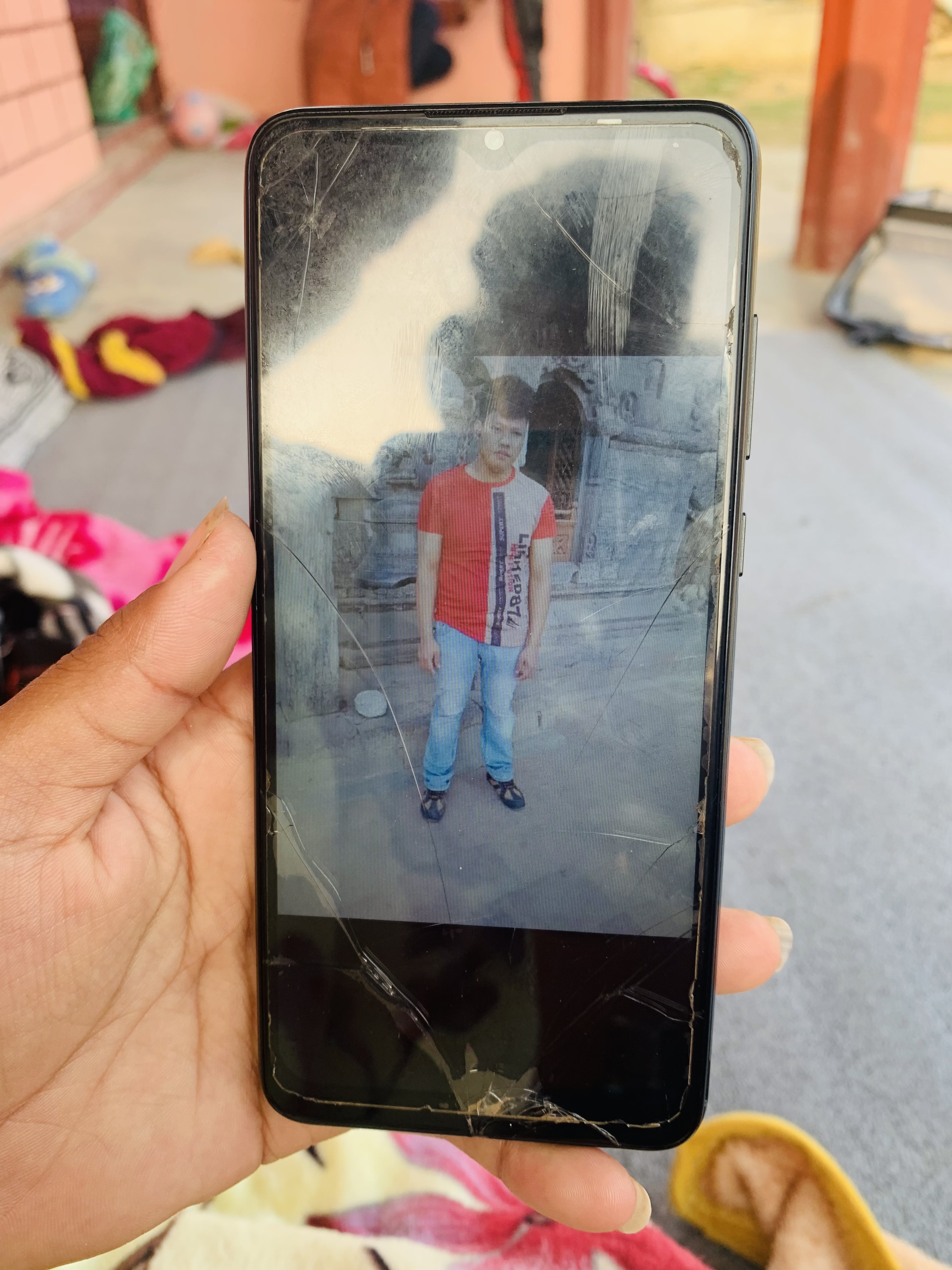

Every evening for several weeks, 27-year-old Dipak Sinjali called his pregnant wife, Kalpana, from a small room in Saudi Arabia, and asked about her health. The two spoke joyously to each other, thrilled that their first baby would be arriving soon. Though living apart was difficult, the regular video calls helped temper the loneliness Kaplana endured in their remote hometown nestled in Nepal's mountains. Now, the wait is over – their baby girl has arrived, but her dad is not here to welcome her.

A week before his daughter’s birth, Dipak returned home in a coffin.

On the morning of November 16, 2021, just 43 days before his daughter’s birth, Dipak was found dead in his bed in the port city of Jizan, in southwest Saudi Arabia. “Had he been alive, he would have been so happy today to see his daughter,” says Kalpana, sitting on the plastic floor mat at her sister’s home in Nepal’s Kapilvastu district. Dipak wanted to come home during her delivery, but not even a year had passed since his last vacation in Nepal, so it was difficult for him to take leave again.

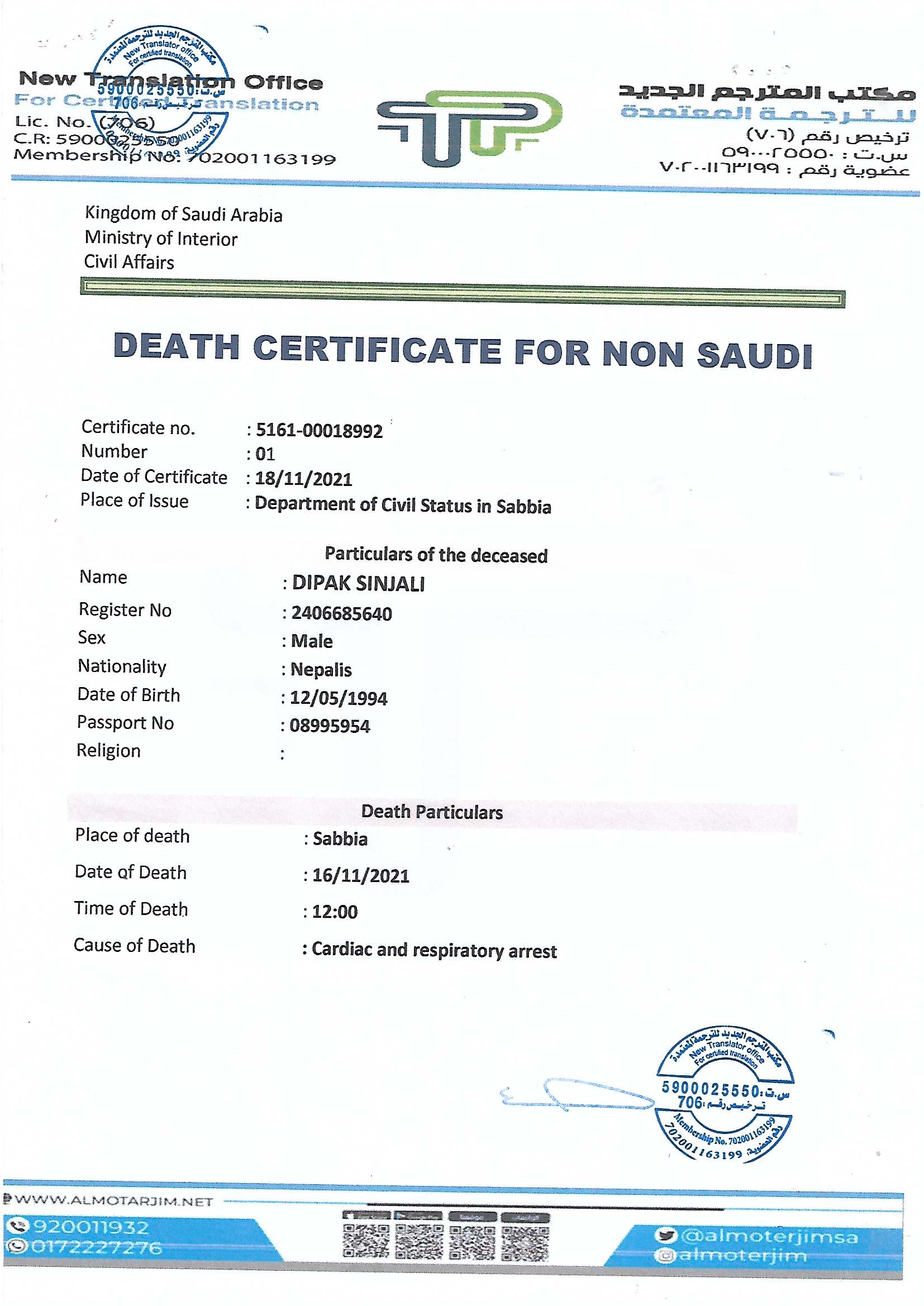

Dipak was a cook at a hotel in Jizan. However, he had gone to Saudi to work as a labourer for Nayarah Trading Est. through Emasco Nepal Pvt. Ltd. in Kathmandu, according to his employment permit. Saudi Arabia’s Ministry of Interior Civil Affairs attributed his death to “cardio and respiratory arrest.” But his family finds it hard to believe. “He had no health issues. I have no idea what happened to him suddenly,” Kalpana says, doubting the circumstances of his demise. But she is aware that his work was not easy. “He would say that he was exposed to heat all the time. I had seen him sweating in the kitchen during the video calls,” she recalls.

As the newborn cries and the sister feeds her milk with a sippy cup, 24-year-old Kalpana, who had lost consciousness for eight hours when she first heard about her husband’s death, looks vacant and gazes up at the sky. “He was so eager to meet her baby. But he was not so lucky, neither are we.”

Kalpana and her newborn are not the only ones in Nepal who are “abhagi” — unlucky — having lost their loved ones overseas. In a previous report, Migrant-Rights.org investigated the high rate of unexplained deaths of Nepali workers in Qatar. As mentioned in that report, the mortality rates in Saudi Arabia are far higher. At least 2,280 Nepali migrant workers have died in the kingdom in the decade ending 15 July 2021, according to Nepal’s Foreign Employment Board (FEB).

The actual number of deaths is likely higher since the FEB’s data only include those whose families have received compensation after death. And, in order to get compensation, a worker must have died within the contract period. Their data also does not include the deaths of undocumented workers or those who migrated via irregular channels. This not only means that the deaths are under-reported, but also that thousands of dependents are left in financial despair, struggling to afford education, healthcare, and even basic survival.

For example, Kalpana, already struggling with postpartum issues, is at a loss as to how she will take care of her daughter. “I don’t know how I can raise and educate her alone,” she says, gently laying down the month-old baby. Her husband, Dipak, who dropped out of school in grade eight due to financial hardship, wanted to see their child well-educated. Fulfilling that dream is now a more difficult task with no source of income. As a cook, Dipak would earn up to SR2,000 per month.

According to FEB data for the fiscal year 2020-2021, the highest number of Nepali migrant worker deaths were reported in Saudi Arabia — a total of 368, or at least one death every day. More than a quarter of these deaths were classified as “natural,” whereas 18% died due to various diseases, including Covid-19. Deaths related to traffic accidents and suicides account for 14% and 12%, respectively. Four per cent of cases involved heart attack and cardiac arrest. In the past decade, over one-third (772) of the total deaths (2,281) of Nepali migrant workers in Saudi Arabia were categorised as “natural.”

“Natural death cases in Saudi Arabia are unnaturally high,” says Anurag Devkota, a human rights advocate who works at the Law and Policy Forum for Social Justice. “It’s a unique and alarming situation there in Saudi; we really need to investigate it. While ‘cardiac arrest’ and ‘heart attack’ are leading ‘causes’ of deaths in other Gulf nations and Malaysia, such a high number of natural deaths in Saudi Arabia appears suspicious,” he added.

The Embassy of Nepal in Saudi Arabia did not respond to MR’s data requests. But the documents issued by the embassy were found to have categorised cause of death as “natural,” even if a worker died for different reasons. Dipak Sinjali’s death is classified as “natural” by the embassy, but he died of “acute cardiorespiratory arrest” according to the medical report issued by the Saudi authority. Bikau Ray, 54, from Mahottari district of Nepal died of “heart and breath failure" in April 2021, according to his death certificate, but his death was classified as “natural” by the embassy.

The reasons cited on death certificates do not shed light on the actual causes. And without understanding the causes, little can be done to prevent these deaths.

“It’s not clear whether Saudi authorities tend to attribute the deaths as ‘natural’ or whether it is the Nepali embassy that mismatched the data,” says Devakota. “Very little research has been done in Saudi since there is minimal access.”

The Nepal government is aware of the increasing number of ‘natural’ deaths in Saudi. “But we cannot do anything since the Saudi government does the investigations. We must rely on the reports received from the Nepali embassy,” admits Rajan Prasad Shrestha, executive director of the FEB.

But he thinks that many of those “natural deaths” are related to the environment, more precisely the high temperature. “Because Nepali workers are not aware of the safety tips such as drinking plenty of fluids and avoiding air conditioning immediately after working in searing heat,” he added.

Uneducated, Unaware and “Unskilled”

For over a year and a half, 43-year-old Islam Pakhiya Budhu has been unable to work without assistance. In a rural village at the Indo-Nepal border of Nawalpur district, Islam spends days and nights lying on the bed in a dingy room of his small brick-walled house. On a stifling hot day in the first week of July 2020, he was working outside, painting the walls at the Riyadh metro station. He suddenly felt uneasy as his body heated up. He took a short break and went back to work again. The next day, his health worsened, and he was taken to a hospital.

“Now, my hands and legs don’t move; the brain also doesn’t function properly,” says Islam, overwhelmed and emotional. He gets disoriented often during the conversation. Islam had undergone surgeries of head and heart while hospitalised for three months at the Mouwasat Hospital in Riyadh, but things did not improve as expected. He returned to Nepal in November 2020.

“He spent his youth there but got paralysed at the end of the day,” his wife Hasina bemoans, helping him put on a woolly hat on a gloomy winter day in Nawalpur. “We are ruined.”

Islam had spent 18 years in Saudi. In that period, he worked for several companies – sometimes as loading labour, sometimes as a scaffolder. In the last eight years, he worked only at the same company in Riyadh where his job was to paint and plaster. With the money he saved over the years, Islam built a tiny house for his 13-member family in Nepal. But he became disabled before he could put the finishing touches — the plastering and painting — on his own home.

“I had a dream to paint this house myself,” he looks defeated.

Now, he is worried about his children’s future. “How can I look after them as I struggle for my own life,” he worries, caressing his school-uniformed little son and daughter, who had just returned from the playground.

With the hope of improving his health, his wife Hasina takes him to a hospital in India every week, but her hopes are shattered every time. “No signs of improvement seen. We are poor people; please try to help,” she says, showing the piles of medical bills. “We don’t have money for his treatment anymore.”

According to his foreign employment permit, in 2018, Islam was hired by K.M.AL-Hammam Est. for Contracting to work as a labourer and his salary was stated as SR 1,500. But he would only receive SR1,200.

In fact, there may be thousands of Nepali migrant workers like Islam in both origin and destination countries. More than 20,000 Nepali workers in the GCC have been forced to leave their job after being disabled, injured, or sick in 2017-2018 alone, according to the 2020 Labor Migration Report.

While lack of awareness amongst workers must be addressed, the onus of ensuring their health and safety, including putting into place stringent occupational safety and health standards, lies with the employer and the governments at destination.

FEB director Din Bandhu Subedi is aware that Nepali migrant workers’ conditions in Saudi are the most dire of all Gulf nations and says the FEB is trying to improve the situation.

“The ones in trouble are mostly uneducated, unaware, and unskilled migrant workers,” he said. “Many of them would not have sustained injuries or suffer from sickness if they were aware of simple stuff such as workplace safety measures or traffic rules.” They may not be fully aware of potential health risks of working in high temperatures – or any risk-prone working conditions – or visit doctors in a timely manner when a complication occurs, he added.

For example, no one took Islam to the hospital, or even suggested he go, on the day he complained of chest pains and numbing on the left side of his body. When he did go to the hospital the next day, he was diagnosed with cerebral infarction, according to his medical report. Cerebral infarction is also known as ischemic stroke, which occurs as a result of disrupted blood flow and restricted oxygen supply to the brain. In his coronary angiogram, a procedure that uses X-ray imaging to see the heart’s blood vessel, he was diagnosed with “[severe] mitral stenosis.” “I went to the hospital the next day; we didn’t take it seriously at first,” Islam says.

Aiming to protect migrant workers, the FEB has revised the curriculum of pre-departure orientation training in 2021. “I believe the new inputs in the mandatory training curriculum would help minimise the deaths, injuries, and illness,” says Rajan Prasad Shrestha, board executive director. “The curriculum includes information on both physical and mental health. It has country-specific information, too.”

While lack of awareness amongst workers must be addressed, the onus of ensuring their health and safety, including putting into place stringent occupational safety and health standards, must lie with the employer and the governments at destination. Saudi’s own OSH laws also require employers to bear this responsibility.

Human rights activists also question the effectiveness of such training and curriculum as hundreds of deaths are still reported every year. “There have been some positive changes in the curriculum, but I am afraid the training institutes would implement it effectively,” says Rameshwar Nepal, a human rights defender who is the Nepal director of Equidem, an organisation that works for human and labour rights. “Because I don’t think we have sufficient skilled trainers and infrastructures to conduct sophisticated training.”

A more up-to-date and focused curriculum certainly helps, but he added that its practical and mandatory implementation is essential to avert deaths and injuries.

In the past ten fiscal years, more than 587 (26% of total deaths in that period) workers died in traffic accidents in Saudi Arabia, 208 (9%) workers committed suicide, and 161 (7%) were killed in workplace accidents. Some of which, Rameshwar thinks, could have been prevented if workers had been well informed about road crossing rules, workplace safety measures, or ways of coping with mental stress.

Phagu Dhami Tharu, 72, at the premises of the Foreign Employment Board to request to repatriate his son Kishor Kumar Dhami’s dead body, who died in Saudi Arabia about five months before.

Phagu Dhami Tharu, 72, at the premises of the Foreign Employment Board to request to repatriate his son Kishor Kumar Dhami’s dead body, who died in Saudi Arabia about five months before.

Islam Pakhiya’ family – wife Hasina Khatun (left), mother Johara Khatun (right), and younger son Ayan Pathan and daughter Nagma Khatun in the front.

Phagu Dhami Tharu, 72, at the premises of the Foreign Employment Board to request to repatriate his son Kishor Kumar Dhami’s dead body, who died in Saudi Arabia about five months before.

Waiting for the son

For almost five months, Phagu Dhami Tharu, 72, has been desperately waiting for his son’s body to return. Phagu has pleaded with Nepal’s local and federal government officials to bring his son’s body back from Saudi.

But his wait continues.

“I want to see my son one last time,” a grieving Phagu says. Despite his age, he travelled to Kathmandu from the southern Bara district, to make a request to the director at the FEB. “I know I won’t see him alive, but please help; I can’t leave him abandoned there.”

But director Din Bandhu Subedi says, swiftly, he “cannot do anything” as the case is under investigation.

Phagu’s elder son Kishor Kumar Dhami used to work as a tile fixer in Tabuk, in northwestern Saudi. The 40-year-old was the father of five daughters and the sole income earner of a family of 14. In September 2021, Kishor Kumar was found hanging in a room at the labour camp. It is not clear whether it was a suicide or a murder. But just a day before his death, he called his wife, Surya Devi, and said he would be coming home in two weeks. The next day, she learned about her husband’s death from another Nepali migrant worker in Saudi.

While Surya and other family members are restless in their hometown, Phagu is wandering the streets of Kathmandu, a blue mask on his wrinkled chin, pleading with officials to bring back the remains of his son.

“Do you know, what is the situation of my son’s body?” Phagu asks the Board director.

“Don’t worry; the body must be preserved in ice,” Din Bandhu replies in earnest.

Kishor Kumar’s family wants a proper investigation into the death and to seek compensation, but now, their priority is to bring his body back.

“The case is being investigated by the Saudi police, so we don’t know when we can repatriate,” Din Bandhu explains to Phagu. “The process for compensation will begin then.”

Phagu still has a little hope to see his son, albeit dead, but he worries about his granddaughters. “How can she [Kishor’s wife] raise those kids alone? How can she conduct her daughters’ wedding – you know well, we have to give dowry for each, and we don’t have money,” he says.

The story of Phagu’s family is tragically common in Nepal, where one-third of GDP comes from remittances.

The process of repatriation is much longer in Saudi than in other countries, prolonging pains in the family. “In the case of natural deaths, it takes around a month,” Din Bandhu says, “but it takes even longer in the cases of suicide, murder, and accident because it requires thorough investigation.”

According to Bandhu, obtaining clearance letters from Saudi police, labour court, and the hiring company is often a protracted process. The Nepali embassy cannot issue a no-objection certificate (NOC) to repatriate remains unless all clearances are made.

“FEB, the embassy in Riyadh and consulate office in Jeddah coordinate to provide services for workers to rescue and repatriate, but it’s still challenging to do it quickly because of an overwhelming number of deaths in such a big country,” he added.

There are about 400,000 Nepalis in Saudi Arabia, dispersed across the country. And two-third of the workers work in the so-called unskilled sectors such as cleaning, laundry, labour, loading, packaging, shipping, etc. Driving and machine operating is the second primary occupation constituting 13% of the Nepali workforce in the Kingdom, followed by service and sales industry at 9%, according to the 2020 Labor Migration Report.

“Problems are prevalent in every sector, but the worst of it is in service, hospitality, and construction sectors,” says Rameshwar Nepal. “The situation of domestic workers could be worse too, but we cannot say it definitively as we have limited access and resources.” Nepal has banned domestic worker deployment to Saudi since 2017, but many workers still travel through undocumented routes.

Amid the rising complaints from workers in distress, the consulate general in Jeddah had reportedly identified vulnerable labour camps with a high incidence of casualties and deaths. Neither the embassy in Riyadh nor the consulate in Jeddah provided the information about those camps and their locations to MR.

But FEB executive director Rajan says that he has received more reports of deaths, injuries, and other work-related cases from Riyadh, Jeddah, and Dammam. “Probably because there are more workers, especially in construction,” he added.

Yam Bahadur has not received any compensation after his son’s death from the company yet. When he talked to the company representative and Nepali embassy in Riyadh, they did not give a clear answer.

Struggles of the stranded

For more than six months, Sagar BK, 29, has been trying to return to Nepal from Dammam, Saudi Arabia. But he does not have his passport with him. Nearly five years ago, when he went to Saudi for the first time, he handed over his passport to the sponsor (kafeel). “Now I want to return home, but my employer won’t give the passport back,” says Sagar from Dammam. “And my iqama [residence permit] has not been renewed for the last three years.” Nor is his employer willing to give him an exit permit. Technically, an employer-issued exit permit is no longer required, however, processes to exit the country still depend on the employer not interfering with the request.

According to his employment contract, he was hired by the Saud Al Falah Al-Sahli Transport Est. as a truck driver, and his salary is SR2,000. But he had been receiving only SR 1,200, which the company also stopped paying three months ago. Sagar had gone to Saudi through New World Overseas Service Pvt. Ltd. in Kathmandu.

“I am helpless; I don’t have money; I haven’t got my salary for three months,” he says. “I have begged for help from many people but to no avail.”

In Nepal, his wife Basanti is also desperately seeking help for him. She visited the Chitwan district office of the Safer Migration Project (SaMi) – a bilateral initiative between the government of Nepal and Switzerland which provides support for migrant workers.

But Sagar is still stuck in Saudi. His colleagues Krishna Bishwokarma and Dipendra BK have been stranded, too. They have been staying in a parking lot in Dammam for a few days, waiting for help.

When Sagar left home, his son was just one and a half years old. Now he is six and repeatedly asks where his dad is and when he can meet him. Please help him return,” Basanti pleads. “My son and I want to meet him.”

Sagar and his colleagues have already requested the Nepali embassy for help. “But the embassy suggested we reach out to the labour office in Khafji,” says Krishna. “We went there too, but, that didn’t work either.”

The Nepali Embassy in Riyadh did not reply to Migrant-Rights.org’s inquiries about these workers’ issues.

Nepali workers in the Kingdom have been subject to a range of human and labour rights violations such as passport confiscation, wage theft, expired iqamas, forceful terminations, squalid working conditions, contract substitutions, according to SaMi officials.

“Violations and abuses among Nepali migrant workers in Saudi are not new,” says Nabin Shishir BK, a counsellor at the Migration Resource Center of the Safer Migration Project, Nepal. “But it looks like the situation has been exacerbated with the Covid-19 pandemic. Because we have got more complaints of forced labour, nonpayment, deduction in wages in recent months.”

Rameshwar agrees. “Workers’ troubles compounded as some employers have taken the pandemic as an opportunity to exploit the labourers,” he says.

In March 2021, Saudi announced reforms to the Kafala system, which allowed migrant workers to change jobs without their employer’s consent after one year of employment, expiry of their contract, or under other limited conditions.

However, the reports of abuse of workers under the kafala system continue, says Rameshwar. “It could have done better to some workers at individual levels, but the situation largely remains the same.”

Another challenge is the lack of bilateral agreement between Nepal and Saudi Arabia, according to the FEB executive director Rajan. “Nepali workers’ issues must be addressed at the government level. Efforts have been made to do the agreement, but I don’t know why it’s delayed.”

Despite the myriad challenges in the destination, low-income and unemployed Nepali workers are compelled to work abroad. Dipak Sinjali’s dad Yam Bahadur, 48, had seen his son’s “untimely” death in Jizan. He remembers how horrifying it was to see his only son’s sudden death at age 27. “I came home with his dead body. “Honestly, I don’t want to go back,” he said. “But what would I do stay here? I have no job. I have no other source of income.”

Yam Bahadur has not received any compensation from the company for his son’s death. He says neither the company representative nor the Nepali embassy in Riyadh has given him a clear answer yet.

Two months after his son’s demise, Yam Bahadur decided to fly to Saudi again, where he worked as a shepherd. “I already spent 14 years in the desert with sheep and goats. I don’t know how many years I will have to stay there. Because I have a debt of NPR1,200,000. And now, I am the one to pay it back,” he says.