Rideshare platforms in Qatar: Big business, poor ethics

Uber and Careem make it easy to violate the labour rights of their drivers

When you land at the Hamad International Airport in Doha, chances are you'll open your Uber (or Uber-acquired Careem) app and book yourself a ride to your destination. Your Uber driver – say Derek from Kenya or Bader from Pakistan – may be local enough, having spent a few years in the country. But all drivers will be Asian or African migrants from developing countries struggling with unemployment, who, as a result, provide a steady source of cheap labour to Qatar and other GCC states.

Unlike the Uber driver (or Careem captain) in their home countries, Derek and Bader do not quite enjoy the independence these app platforms promise. In Qatar, Uber requires that the drivers be sponsored by a limousine company and that their vehicles also be registered under a limousine company.

In fact, the drivers are exploited twice over – by being excluded from any labour protections by Uber and Careem, whose main relationship is with the limousine company, and denied the labour protections that technically exist by law, as a sponsored employee in Qatar. They end up working 80 to 90 hours a week in order to save money after meeting expenses — they pay an exorbitant 25% of all fares to the app, and another bunch of fees that add up to a few thousand riyals annually, to their kafeel.

The migrant drivers are unlikely to own their vehicles and even those who own vehicles, usually through mortgages paid to the sponsor, will have to pay a fee to their sponsoring limousine company, since Uber’s terms stipulate that the drivers in Qatar must be associated with a limousine company. The terms are different in Dubai and Abu Dhabi but just as exploitative – showing pragmatic flexibility in ensuring profits, but in complete denial of the price drivers pay for that. [see sidebar 1]

In an article on the gig economy, UAE-based law firm Al Tamimi & Co draws attention to a lack of flexibility in GCC legal regimes that do not accommodate different business models and points out that not only are the Uber and Careem models in the region different from other jurisdictions but that “the individuals (such as the drivers of the Uber cars) are entitled to the same statutory protections as all other employees in the UAE.” In practice, these protections do not exist, either in the UAE or elsewhere in the GCC.

For countries like Qatar, where public transport systems are still in a nascent stage, there is an extremely high dependence on privately-owned vehicles and taxi services. About a decade ago, ‘orange’ taxis which were owned either by the drivers or their sponsors were the main public transport facility were discontinued. Drivers were given the option to u join the fleet operated by the state-owned Mowasalat, which operates the Karwa taxi service. Karwa also franchises its services to businesses and has an app service similar to Uber or Careem. However, the familiarity of a global app steers most people, residents and visitors included, towards Uber.

Profit without accountability

Migrant-Rights.Org interviewed dozens of drivers from Nepal, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Kenya and Ghana, both individually and as informal groups, and their experiences are strikingly similar. The drivers all work in grey areas of the labour law, having the appearance of complete autonomy over the terms of their employment, though in reality, remaining inextricably linked to their sponsor.

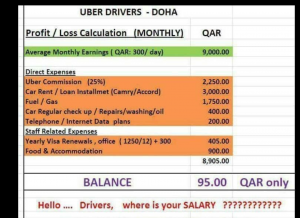

There is general grouse against the apps for being extractive. In 2017, hundreds of Uber drivers in Qatar protested price cuts that made it even more difficult for them to break even. More recently, Uber drivers have been registering their concerns in private WhatsApp groups and Facebook pages. One Facebook page calculates the costs incurred by the drivers, showing the paltry amount they are left with at the end of the month. [see image]

One group interviewed by MR, all employed with different limousine companies but from the same country of origin, said they did not mind paying the sponsor the visa or car rental fees, but that paying such a steep commission to Uber and Careem seemed unfair. “Because when we are in trouble they don’t help us, we still have to go to our sponsor.”

What they pay to their sponsor varies. Those who own their cars do not pay the rental fee but pay a monthly fee of QR300 to QR500 (US$80-US$140) in order to use the limousine company sticker. Those who rent their cars from the limousine company pay a daily rental of QR90 upwards (depending on the make of the car), paying between QR3000 and QR4000 (US$825 to US$1100) a month.

Both categories of drivers bear all costs of vehicle insurance, maintenance, fuel, visa renewal, and health card, with annual costs adding up to QR3000 or more. This amount excludes the refundable deposit paid to the sponsor and recruitment fees paid. The deposit is used to trick the wage protection system (WPS). Drivers pay a refundable deposit of around QR1800 (US$495) to the sponsor. This amount is deposited and withdrawn monthly by the employer, in the WPS account linked to the driver’s work permit. None of the drivers we spoke to had access to the bank card or the money.

One Facebook page calculates the costs incurred by the drivers, showing the paltry amount they are left with at the end of the month.

Technically, the drivers registered with Uber/Careem are not independent drivers but sponsored employees governed by the labour law of Qatar. However, articles of the law are selectively implemented. The driver’s work permit is linked to their residence permit, both under the sponsor, and they still need the sponsor to sign off on a job change or to renew their residence and work permit. The sponsor’s legal and contractual obligation to accommodation, food, minimum wage, health care, and end-of-service benefits are unmet, merely words on paper.

Derek first came to Qatar from Kenya six years ago. He had worked for Karwa taxi previously and is now employed by a private limousine company, using the Uber and Careem apps to solicit clients. He says everyone employed by the limousine company receives a contract in compliance with the format prescribed by the Ministry of Labour. Allowances for accommodation, food, and basic pay are mentioned. However, in practice, none of this is provided. “But we earn more than we would with a regular job. The problem is when things go wrong. Like during Covid... we had to struggle. Some limousine companies waived rental fees, but some of my friends work for companies that made them pay after the business picked up. We had to move into cramped accommodation and struggled to survive.”

The entire gig arrangement is clearly in violation of the labour law but no one is complaining, as the drivers earn more this way than if they were to be hired in a regular manner, albeit they work long hours, without off days or any benefits. The government, businesses, and the gig platforms are complicit in maintaining and keeping silent about this status quo. After all, when there is so little respect for the basic rights of workers in general, that they are likely to earn more than the QR1000 minimum wage appears to justify profiting from even more exploitation.

Derek’s compatriot, Kevin, says his sponsor provides accommodation and a vehicle, but charges QR500 for the former and close to QR3000 a month for the latter. Kevin, who has been in Qatar since 2019, says it’s still lucrative for him, that he enjoys the flexibility of his work hours, and that there are days when he makes as much as QR400 or QR500 (US$110-140). “But on average, it is QR250 (US$70) a day if I work for 12 or 13 hours. Of course, 25% of that will be taken by Uber,” he says.

While the majority of drivers seem resigned to the arrangement, not all were aware of it at the time of recruitment, and many paid hefty recruitment fees back home. Derek remembers paying about USD$1000 in recruitment fees when he first arrived. “That’s the average amount even now. Some drivers know that they will have to work on a commission basis and won’t receive a regular salary, and they take that calculated risk, but many are blindsided once they arrive, as they expect their contract to be respected.”

According to Derek and other drivers MR spoke to, even if workers are shocked at first, in the long run, they still make more than the paltry minimum wage. But that does come at a steep price. “We never take an off day. We have no family here. So we keep working and working, at least that way we can make more money. What is there to do even if we take off, everything here is expensive. So we work every day, for 12 or 14 hours, switching between Uber and Careem apps. But we also take breaks whenever we like. We don’t have to stick to a schedule,” says Sanjay, who moved to Qatar from Nepal in 2018, having paid roughly US$800 in recruitment fees.

When things go bad

The autonomy of work is welcome as long as business is good, but when things go south, like it did during the early months of the pandemic, the drivers take a huge hit.

“See if we get a fever or stomach pain we can take rest for a day and make it up with extra hours later in the month. Corona was different. We didn’t know when it would end. Even when things were bad, Uber and Careem didn’t reduce their commission. Even some of our sponsors reduced the rent we have to pay for the cars. But those companies kept deducting 25%,” Sanjay says. (In January 2022, Careem announced that it was slashing fares and reducing its commission to 20%.)

Bader moved to Qatar just before the pandemic in late 2019. He had worked in Saudi Arabia for several years but had to go back to Peshawar, Pakistan, as he had problems with his sponsor. “I used to have a big American car. A GMC. There is a lot of money to be made in intercity travel in Saudi because the country is so big. But then things became difficult, and I had to move. From my village there are lots of people in Qatar so I decided to come here, and paid QR9000 (US$2500) to cover all costs.”

Bader was under the impression he would be able to buy his own car and only pay the sponsorship fees, as he had done in Saudi. “I paid so much to come here only on those conditions. Then my kafeel said I have to pay car rent to them every month and can only use their car. I pay nearly QR4000 every month. If I had bought the car it would have been an investment, now it’s just money I am losing.”

He says not all limousine companies are bad. “I have brought so many of my family and friends from my village here. They work for better companies. But my sponsor is not even allowing me to change jobs. He says I have to finish three years before I can do that.”

The job market for drivers is growing steadily and is likely to hit a peak closer to the World Cup end of the year. Though the number of registered limousine companies is not publicly available, an aggregate of different business directories shows around 150 in operation. This is set to grow, with more drivers being recruited into the sector. Job boards on social media are flush with advertisements by limousine companies for Uber drivers. None of these advertisements is transparent with the terms of employment.

Migrant-Rights.Org reached out to both Uber and Careem requesting a response to a set of questions [see sidebar], but only the latter responded.

“Careem provides a marketplace for both GCC nationals and non-GCC nationals to work as Captains. We have created earning opportunities for over two million Captains across the region.

Some of our Captains own their vehicles while others rent them from fleet owners. Careem does not take fees from fleet owners or deduct sponsor fees from Captains. We do provide in-ride insurance that covers both our Captains and our customers.”

A follow-up question as to what the insurance entails remained unanswered.

Baker Khundakji a spokesperson for the International Transport Workers’ Federation (ITF), in a comment to MR, pointed out that Qatar and the UAE were among the only parts of the world where rideshare drivers are actually employed because the independent contractor model is not permitted in this sector. “However, rather than working directly for Uber, drivers are hired by a taxi fleet company and seconded to Uber. As the ‘economic employer’ in this kind of relationship, it is important to hold platforms jointly responsible for the health and welfare of rideshare drivers. This is especially true given the precarious status of an entirely migrant workforce. The responsibility for decent working conditions cannot be outsourced,” she added.

The ITF also advocates for the full application of their Gig Economy Employer Principles in the region and called on major platforms like Uber to join this process. The principles include that employment status must be correctly classified and disguised employment relationships must end. On the contrary, in the GCC, Uber thrives under misclassification and the disguise of employment relationships.

Other key principles of ITF are freedom of association, living wages, fair digital contracts, and most importantly access to social protections like healthcare, insurance and other benefits. The labour laws of Qatar (and other GCC) countries have relevant provisions covering most of this. But it is denied to Uber drivers because of the nature of the mutually beneficial contract between the ridesharing platform and the business owner, which withholds these rights from the drivers.

Valerio De Stefano, of the International Labour Organisation, says that by using terms such as ‘gigs’, ‘rides’, or ‘tasks’, the jobs are not designated as work nor the employees as workers, indicating “a sort of parallel dimension in which labour protection and employment regulation are assumed not to apply by default.”

The gig economy “may enable workers to benefit from job opportunities that they might not be able to access otherwise and on a flexible schedule” and assumes “to equate the undisputable flexibility the gig-economy generally affords to businesses.”

However, in general, it disguises the employment relationship and introduces non-standard forms of employment that reduce the responsibility of the business and increases the burden on the worker. In the Gulf region, in particular, it takes on a more vicious form, where the gamut of exploitative provisions of the Kafala system are amplified, with none of the labour law’s minimum protections.