Social protection is a universal human right enshrined in many international human rights and labour standards. It ensures access to medical care, health services, and income security, throughout the life cycle, particularly in the event of illness, employment injury, maternity, family responsibilities, unemployment, disability, loss of the family breadwinner, as well as during retirement and old age.

Source: Authors, using figures from ILO (2023)

Over the last century, social protection systems have seen impressive growth. Yet just over half of the global population — more than 4 billion people — still lack access to any social protection benefits.

Globally, migrant workers often lack access to social protection due to both legal and practical restrictions. Lack of adequate and comprehensive social protection means migrant workers often have no option but to continue working — and may be unable to afford healthcare altogether — when sick or pregnant. It can mean they bear the costs of injuries in the workplace, and often leaves them or their families facing financial insecurity when their ability to work is halted by old age, disability, or death.

Social protection in the Gulf region

The challenges of extending social protection to migrant workers are acutely evident in the GCC (Gulf Cooperation Council), where migrants comprise 75 - 95% of the workforce. While social protection for migrant workers in the region was a mounting issue before Covid-19, the pandemic emphasised its urgency. Gaps in social protection systems left many without any income when they were unable to work due to sickness or pandemic restrictions, or having been laid off during company closures.

A key first step in strengthening social protection for migrant workers in the region is to understand the provisions currently available to them:

- What social protection entitlements do migrant workers currently have?

- To what extent can migrant workers access these entitlements in practice?

Drawing on a recent report on National Social Protection Legislation and Legal Frameworks for Migrant Workers in the Gulf Countries – part of an ILO-ODI collaboration aiming to extend social protection to migrant workers through research and policy dialogue – this article explores the first question. A second article later this year will share findings on the second question, based on upcoming research.

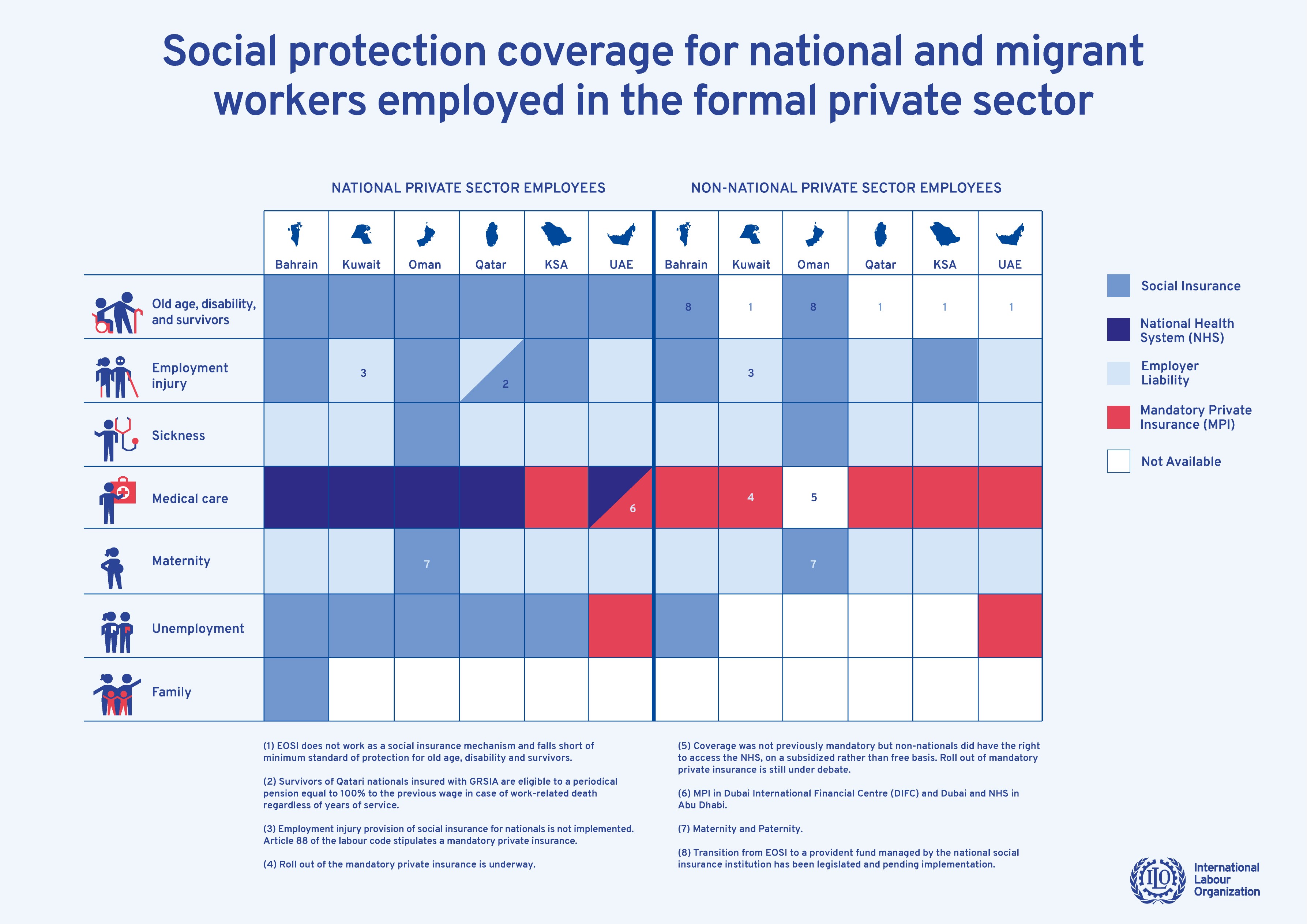

Social protection provisions: public versus private sector

The labour market in the GCC is segmented: the vast majority of GCC citizens are employed in the public sector, whereas most migrants work in the private sector. This informs social protection provisions: public sector jobs are generally better paid with more generous social protection entitlements for citizens, while social protection in the private sector is typically much weaker.

Many provisions for private sector employees rely on ‘employer-liability’ arrangements (as opposed to social insurance systems). Employer liability means that individual employers are directly responsible for paying benefits, for example when a worker gets injured at work or requests to take time off for sickness or pregnancy.

Such arrangements may pressure workers not to take sick or maternity leave, or encourage employer discrimination against recruiting or maintaining contracts with workers with declared conditions. Additionally, small enterprises may struggle with the financial implications, creating an incentive to hire workers informally or reducing compliance with provisions.

More generally, employer-liability provisions are difficult to monitor and enforce. Since the employer individually bears the responsibility for benefits, workers may be left unprotected in case of financial difficulties or bankruptcy. Complaints are often challenging to pursue since the Kafala system dictates that migrant workers must leave the country shortly after the termination of their contract. Furthermore, grievance processes are lengthy and will prove to be expensive if workers were to stay back without a job to fight the case.

Discrimination between migrants and citizens

Alongside these limitations in private sector provisions, social protection provisions are weaker still for migrant workers, since the law often fails to recognise the principle of equal treatment between nationals and non-nationals.

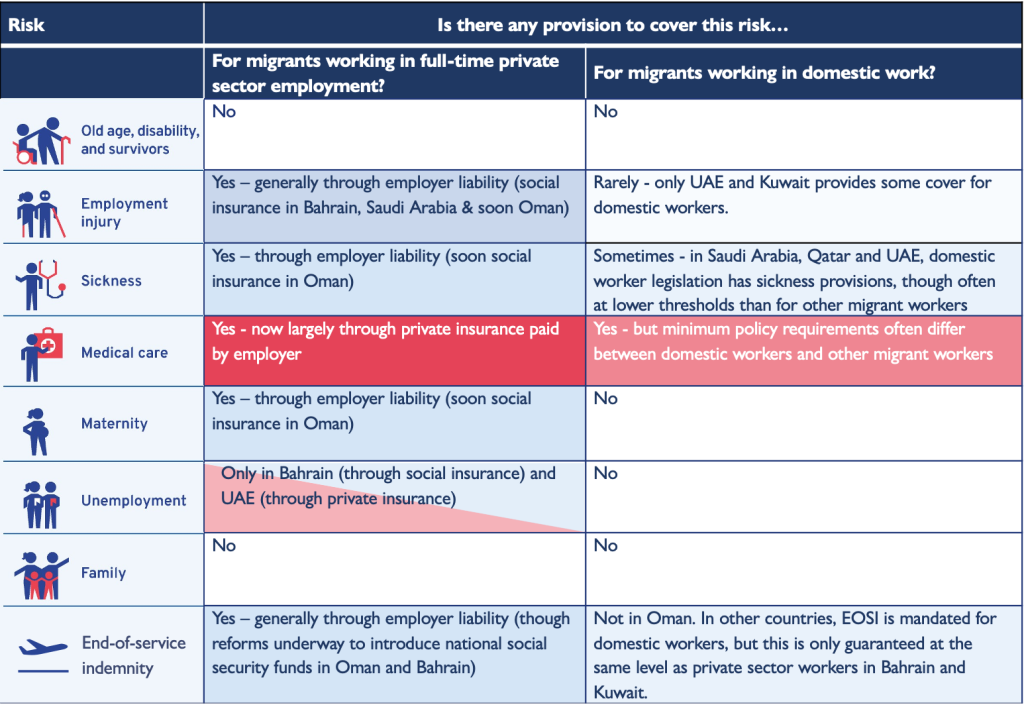

Access to health care for migrant workers is increasingly provided on distinct terms to citizens. In addition, migrants are often excluded from social security rights that fall outside a specific employer-employee relationship. For example, migrants have no rights to family benefits, unemployment benefits (in all cases except Bahrain, and recently the UAE through employee-funded private insurance), as well as old age, disability and survivor’s pensions. Instead, the only widespread entitlement for migrant workers is End-of-Service-Indemnity (EOSI), a lump-sum paid at the end of employment.

Exclusions for certain types of work

There are almost no entitlements for those in part-time, seasonal, casual or self-employed work. It should be noted, however, that in the GCC, workers in the platform (or ‘gig’) economy are typically hired as employees of a company which outsources their labour to digital platforms. They should therefore be covered by the same provisions as other private sector employees, rather than being classified as ‘self-employed’.

Domestic workers have also historically been excluded, though some entitlements have been extended to them over the last decade (discussed below). Those lacking a regular residence or work visa have no rights to social protection, except for emergency healthcare.

Positive developments

Against this challenging backdrop, there are some positive indications of reform.

First, there is some evidence of a shift away from traditional employer-liability provisions, towards the inclusion of migrant workers in national social insurance systems. In Bahrain and Saudi Arabia, migrant workers are in principle legally allowed access to social insurance systems on equal terms with nationals for protection against employment injury – and also unemployment in Bahrain (though access in practice remains very limited). Most recently, Oman passed a law that paves the way for a new model in the region; granting migrant workers access to national social insurance coverage for sickness, maternity and employment injury, on equal terms with citizens.

While migrants continue to be excluded from pension systems, some countries in the region have announced, or are considering, reforms to change End-of-Service Indemnity arrangements so that payments can be made via national social security institutions, as in Bahrain, since 2022 as per Law 14/2022, and in Oman, where the creation of a provident fund to replace the EOSI was enacted in July 2023 and will come into force over the next three years (Decree 52/2023). This should enable greater state oversight and enforcement.

While domestic workers fall outside the scope of the labour law in most GCC countries, the past decade has also seen reforms to develop new legislation for domestic workers, granting them labour protection rights – including some social protection entitlements. This means that in all countries except Oman, domestic workers have the right to health coverage and an End-of-Service Indemnity – and sickness and employment injury benefits in some cases. Even so, the scope, adequacy and financing mechanisms of provisions for domestic workers often fall short of provisions for other workers in the private sector.

Source: Authors, based on ILO (2023)

Growing concerns

While there have been some positive developments in social protection provisions, there are cases that warrant significant concern.

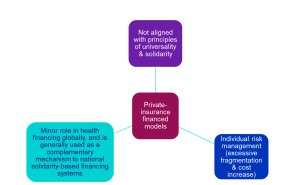

One such trend is the emergence of mandatory private insurance to extend certain forms of protection to migrant workers. This approach risks greater inequity in provisions, increasing costs and exclusion, and failing to deliver on the principles of broad-based solidarity and the role of the State as guarantor of social protection.

With the exception of five UAE emirates, employer-funded health insurance for migrant workers will soon be mandatory for all GCC countries, typically through a private insurance model. In the UAE, all private sector employees are now mandated to pay the full cost of private unemployment insurance. In the Dubai International Financial Centre, End-of-Service-Indemnity arrangements are being replaced by a privately-run mandatory savings scheme.

This adoption of fragmented private-insurance based solutions needs to be reassessed in light of international social security standards, as it risks deepening segmentation in entitlements and access between migrant workers and nationals. Careful monitoring will be required to ensure these solutions do not translate into a decline in quality and yield an increase in out -of pocket payments.

Recommendations

Despite areas of notable progress, many gaps remain in social protection entitlements for migrant workers in the GCC – and some of the measures to fill these gaps are themselves a cause for concern.

Various policy measures are therefore needed to strengthen the legal provisions covering migrant workers in the region, including:

- Further ratification and implementation of conventions and international standards relating to social protection – to date, these remain largely unratified by GCC countries.

- Halt and reverse the concerning trends that have been documented; including where national social protection systems have been further fragmented through private-insurance-based solutions.

- Ongoing adjustments to employer sponsorship arrangements must be paired with effective social protection arrangements to correspond with migrant workers’ increased mobility in the labour market.

- There is a need to determine how migrant workers can be protected against the long-term risks they face when they return from GCC employment – including through stronger social security coordination between countries sending and receiving migrant workers.

In addition, efforts are needed to sustain positive reform trends to:

- Reduce the gap between public and private sector provisions,

- Extend social protection legislation to cover all workers in diverse forms of employment,

- Enhance migrant workers’ inclusion in national social insurance systems,

- Strengthen the role of public social insurance systems based on collective financing from workers and employers as a cornerstone of social security.

- Enhance dialogue between countries of origin and destination to facilitate portability and exportability of benefits.

Of course, policies alone are not sufficient to change the day-to-day experience of migrant workers. To safeguard workers’ rights in a meaningful manner, efforts to extend legal provisions need to be coupled with steps to ensure entitlements are accessible in practice.

Stay tuned for the second article in this series later this year, where we will draw on research with migrant workers and other stakeholders, to explore actual access to entitlements – and the steps needed to improve migrant workers’ effective coverage across the GCC region.