In 2013, Migrant-Rights.org will roll out a new initiative to produce an innovative analysis of the state of migrant rights in the Gulf and wider Middle East. The following assessment of migrant rights in 2012 is a primarily qualitative evaluation, but nonetheless provides critical insight into the current status of migrants rights and establishes a benchmark for the next year.

In 2012, GAMCA policies were one of the most salient issues amongst Migrant Rights readers. Prospective migrant workers are required to undergo medical testing from GAMCA approved facilities, which operate by GCC-devised standards. According to these guidelines, individuals recovered from TB - who are medically healthy and pose zero risk to others - are banned from employment in the Gulf. Migrant Rights received almost weekly correspondence from prospective workers unduly disadvantaged by these policies, many of whom were further agitated by medical centers' poor or misleading services. Unfortunately, few international organizations were willing to publicly condemn GAMCA's discriminatory practices. GAMCA's policies consequently remain in effect, largely unchallenged by any influential actors or institutions.

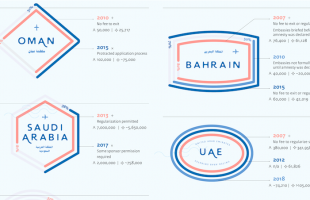

Nonetheless, legislation (or commitments to past legislation) are generally poor indicators of the actual conditions migrants face. The International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of their Families and the ILO convention on Decent Work for Domestic Workers still remain either unratified or unimplemented throughout the region. Furthermore, at the Abu Dhabi Dialogue II in Manila, a summit intended to resolve labor issues between sending and receiving nations, Gulf nations pressed to keep domestic worker regulation out of negotiations. Additionally, promises by Saudi Arabia and Lebanon to abolish the sponsorship (kafala or kafil) system, perhaps the region's single most repressive institution affecting migrants, still remain in the inchoate (and unpromising) stages. Similarly, commitments to implement labor reform from the UAE, Qatar, Kuwait, and Bahrain remain entirely unpursued or effectively unenforced. In the event that labor legislation is actually passed into law, the absence of effective enforcement mechanisms renders their intent impotent.

The failure of public or legislative commitments to impact migrant welfare is evident in that laborers continued to experience harsh, unsafe working conditions: A Pricewaterhousecoopers report on the UAE's Saadiyat islands project illustrated the consequences of insufficient and under-enforced regulations; exorbitant fees, illegal salary deductions, and substandard housing conditions comprised enduring transgressions in one of the nation's most high-profile projects - casting little hope for laborers toiling in the nation's less scrutinized endeavors. In Bahrain, 10 Bangladeshis were killed in a fire that struck an uninspected makeshift labor camp and a Pakistani window cleaner fell 17 floors to his death because he was not provided with (mandated) safety harness equipment. The Bahraini government eschewed responsibility for either case because the migrants were considered illegal. Although none of the men had entered the country illegally, the inflexible sponsorship system - which Bahrain had promised to reform in 2009 - prevented the men from legally extending their employment visas or supplementing their contemporary employment. In Saudi Arabia, two Pakistani and Egyptian laborers fell from two separate structures they were building. These anecdotes comprise only a small handful of the labor abuse cases reported in media, which furthermore represent an unknown fraction of the actual number of incidents. Nonetheless, these transgressions evidence the invariable reality of labor practices in the region.

Similarly, the absence of meaningful protective legislation has sustained the abuse and exploitation of domestic workers. This year, two separate instances of brutal video coverage provided a glimpse into this harrowing reality: the shocking public abuse of Alem Deschesa, who later committed suicide, and the Lebanese authorities’ violent arrest of another domestic worker. Documentation of abuse, suicide, and financial exploitation constantly frequented Migrant Rights's twitter feed and monthly roundups; the disturbing reports of forced prostitution, captivity, slavery, torture and murder represented only a fraction of the violence committed against domestic workers. Furthermore, Migrant Rights tweeted over 60 cases of suicide this past year. This number, though astonishing, is likely an underestimation. Migrant Rights did not tweet every story of suicide, particularly as many such cases do not receive press coverage.

Moreover, domestic workers continued to be denied the right to basic self-autonomy. No relationships are allowed outside of marriage, under the pretense of cultural sensitivity. Domestic workers still have few means to redress issues with their employers, enabling abusive conditions to compound over time and eventually lead to absconsion or suicide. Furthermore, absconding workers are still criminalized, rendering physical escape a particularly daunting and dangerous endeavor. Worker's own consulates are unreliable in their ability to provide workers with aid or prompt repatriation. Consequently, many workers are forced to endure abuse for an indefinite and isolated period of time.

Overall, few, if any, positive developments for domestic workers emerged this year. Sending countries including Nepal and Indonesia implemented reactive bans to nations determined "particularly dangerous," which in turn prompted receiving states to pledge reactive reforms. Even in the case of signed agreements, reforms are still exceedingly slow to implement - as of yet, no real impact can be discerned from any of the bans concluded this year. In most cases, bans were reversed prior to the full actualization of these commitments.

Similarly, though a few judicial verdicts in the UAE and Saudi Arabia sided with domestic workers, these rulings must be contextualized by the reality most domestic workers experience: most cases are never even registered with the government because of the absence of domestic labor regulations (domestic workers are still excluded from the regulations that govern laborers) or an effective enforcement system. Some cases may have individually positive outcomes, even though the employer's punishment is often incommensurate with the crime, but they reflect the indolent, reactive attitudes of Gulf authorities. Such isolated resolutions do not encompass actual solutions capable of addressing the endemic violations perpetrated by the region's broken labor system.

Furthermore, recruitment agencies also continue to operate without significant regulation. Agencies and employment offices contribute significantly to the exploitation and deception of migrant workers. Many charge exorbitant or illegal fees, and mislead migrants regarding the terms of employment. Sending and receiving governments not only fail to take accountability for these exploitative practices, but furthermore delegate agencies with the responsibility of monitoring workers. For example, UAE officials indicated agencies must ensure employers pay migrants according to the minimum wage and provide them with adequate living spaces. Yet, essentially no mechanism exists to monitor recruitment agencies to ensure these duties are fulfilled. As a result, domestic workers in the UAE continue to be underpaid. Similar conditions permeate the region, and similarly reflect the reality of sending nations’ lax governance, though some states have begun to crackdown on agencies in isolated incidents. In response to this enduring government oversight, Ethiopian citizens began to develop a unique private sector solution which may serve as an example for other sending nations.

Some positive and critical discussion of migrant rights did take place in Gulf narratives, though they were often overshadowed by bigoted and misleading features. Still, the increased frequency of these reports that recognize the basic rights of workers in Gulf and other Arab papers is a critical advancement in the perception of migrant workers. Furthermore, civil society activism took off this year, in the form of powerful PSAs and public demonstrations. Though primarily originating in Lebanon, their messages have far reaching impacts across the region, and the potential to inspire similar activism in other nations.

The new year will likely be marred by the same empty promises and pervasively abusive practices. But if similar civil society activism spreads through the region, meaningful change can be initiated from the civic level and prompt government reform to follow suit. Migrant Rights will continue to promote the humanization of migrant workers alongside our audiences in the Middle East and across the globe.