Amnesty exposes extreme abuse on World Cup sites; ILO gives Qatar one more year to clean up its act

Two recent reports have highlighted the systemic violation of migrant workers’ rights under Qatar’s labour management system.In its latest report, Amnesty International spotlights unregulated sub-contractors who go rogue.

The International Labor Organization (ILO), while recognising efforts taken to end forced labor, noted that the reforms have not gone far enough to end forced labour, and gave Qatar a year to set it right. The new sponsorship law comes into effect from December 2016, but the changes announced last year fail to live up to Qatar’s promises.

If the ILO sees no progress, Qatar will be subjected to a commission of inquiry, which is the ILO’s highest level investigative procedure, and is launched when a member state is accused of persistent violations and refusal to address them.

Here is a quick over of the ILO and Amnesty findings:

ILO: Complaint concerning non-observance by Qatar of the Forced Labour Convention, 1930 (No. 29), and the Labour Inspection Convention, 1947 (No. 81), made by delegates to the 103rd Session (2014) of the International Labour Conference under article 26 of the ILO Constitution.

With respect to living conditions, the tripartite delegation was able to see in the Sailiya Workers’ Accommodation that their accommodation does not satisfy by far the minimum standards, with most accommodation housing ten to 12 workers per small room, unhygienic and poor kitchen and sanitary facilities. These workers were not aware of nor did they benefit from the electronic payment of wages through the establishment of the newly established WPS.

...the tripartite delegation observes that the ILO Committee of Experts on the Application of Conventions and Recommendations noted, in its most recent observation of December 2015 on the application by the Government of Qatar of Convention No. 29, that a number of provisions of Law No. 21 still places restrictions on the possibility of workers to leave the country or to change employers and would prevent workers who might be victims of abusive practices from freeing themselves from these situations. The tripartite delegation considers that further information on the effects of Law No. 21 under its implementation stage is needed to assess the effects of the measures in place, and it is important that the implementing regulations be clear.

The ILO also took note of Qatar’s deliberate exclusion of domestic workers from its labor law, and domestic workers’ continued isolation and vulnerability, with no solution in sight.

The tripartite delegation took note that migrant domestic workers are regulated by the provisions of the national civil law and criminal law, since they are excluded from the scope of both the Labour Law of 2004 and Law No. 4 of 2009 regulating the kafala system. Moreover, Law No. 21 of 2015 will not apply to them once it enters into force in December 2016. A draft bill on migrant workers has been pending since 2012 but there is no time frame for its adoption. Given that the system of employment of migrant domestic workers could place the workers concerned in a situation of increased vulnerability and in light of their large number in Qatar, the tripartite delegation considers it essential that prompt and effective action be taken to protect them in law and in practice without delay.

The tripartite delegation did acknowledge recent measures taken to improve domestic worker conditions, but the impact of the new laws could be evaluated only after it’s implemented.

You can read the full report ILO Qatar.

The Khalifa International Stadium in Aspire Zone is being refurbished for the World Cup. Photo courtesy Amnesty International

Amnesty International

Amnesty International has investigated migrant worker abuses over the last several years.

Qatar: The Dark Side of Migration, a spotlight on construction sector ahead of the world cup in November 2013; ‘My Sleep is My Break’ in April 2014 highlighting the extreme exploitation and abuse of migrant domestic workers; and No Extra Time: How Qatar is still failing on workers’ rights ahead of the World Cup in Nov 2014.

In its latest report, released 31 March 2016, The Ugly Side of a Beautiful Game Amnesty International highlights the narrow application of worker welfare standards that adopted by organisations including the Supreme Committee for Delivery and Legacy (SC) and Qatar Foundation.

The report found that the standards do not go far enough to cover sub-contractors.

Highlights from the report:

In 2015 Amnesty International identified more than 100 migrant workers employed on the Khalifa Stadium who were being subjected to human rights abuses by the companies for which they worked. The organization also found that the labour rights of migrant workers involved in landscaping green spaces in the Aspire Zone surrounding Khalifa Stadium were being abused by their employer.

Many of the migrant workers who spoke to Amnesty International reported arriving in Qatar to find that the terms and conditions of their work were different from those that they had been promised by recruiters in their home country. The main form of deception that workers reported was with regard to salary. All but six of the 234 men interviewed told Amnesty International that, on arrival in Qatar, they learned that their salaries would be lower than the amount they were promised. Deceptive recruitment practices increase workers’ vulnerability to trafficking for labour exploitation and forced labour. Having paid fees and, in many cases, taken on debt to move to Qatar they felt they had no option but to accept the lower salaries, although many were then left in very difficult situations, struggling to repay loans with less money than expected.

As far as Amnesty International is aware none of the workers whose cases are documented in this report brought a complaint to the authorities about the human rights abuses they were experiencing. Amnesty International raised the abuses at Khalifa Stadium and the Aspire Zone with the Government of Qatar, in writing. The government’s response did not address any of the specific abuses, despite the fact that several of the cases involved breaches of Qatar’s laws.

[...] there are some fundamental problems with the Supreme Committee’s approach to monitoring and enforcing the Workers’ Welfare Standards, as demonstrated by the abuses discovered on the Khalifa Stadium project. Firstly, although the Standards are supposed to apply to all companies and workers on World Cup projects, the Supreme Committee has focused on compliance by the main contractors. This approach ignores the evidence that migrant workers’ rights are generally at greater risk when they are working for small sub-contractors and labour supply companies. Some of the most egregious abuses that Amnesty International documented on Khalifa Stadium were perpetrated by labour supply companies that the Supreme Committee did not even know were involved with the Project.

The report also says the men seeking assistance were threatened, and the workers were fearful of being fired and sent back home without their dues.

The Amnesty report highlights one of the main problems facing Qatar’s labor market – the warehousing and deployment of workers, to various sites, such that no one main contractor is responsible for their well being, and the main clients often absolve themselves of any responsibility.

Hundreds of labour supply companies operate in Qatar, often bringing in migrant workers solely for the purpose of sub-contracting out their labour to other companies. Having brought migrant workers into Qatar small labour supply companies (also described as “manpower companies”) are frequently unable, or unwilling, to ensure migrant workers are paid on time or provided with documents that require the payment of a fee, such as residency permits. They can also be unwilling to let workers they view as an “investment” leave the country.

Key recommendations include:

- Increase the monitoring of the arrival of workers in Qatar, so that when workers arrive their contract is checked by government officials in the presence of their employer and the worker, to confirm that the terms and conditions are what the worker has been promised prior to leaving his or her home country.

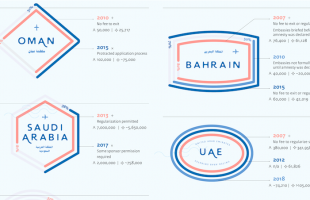

(Qatar has said it would introduce an electronic contract system, but unlike in the UAE, it would not be mandatory for all companies to adopt.)

- Adopt regulations setting out the safeguards which a labour supply company must have in place before sponsoring any migrant workers, ensure that these regulations are enforced, including through monitoring and regular inspections of labour supply companies.

- Apply the Supreme Committee Workers’ Welfare Standards to all businesses involved in World Cup projects, regardless of their size or the length of their contract.

Qatar’s response to Amnesty’s report predictably mentions the Wage Protection System, increased labor inspections, and the blacklisting of violating companies: 1800 inspections of recruitment companies; 375 new labor inspectors; 56,000 inspections in 2015; and 923 companies banned from operation in Qatar.

The SC in its response said it "respectfully rejects AI's statement that SC has 'failed'. We have always stated that time is required to continuously improve the situation, and we believe our core stakeholders will support us on this journey."

While the above-mentioned reforms indeed represented progress one or two years ago – and were recognized as such by Amnesty and the ILO – they can no longer be considered progress; they were then touted as the first of more expansive labor reforms – as intermediary steps towards a fundamental overhaul to the Kafala system. Instead, these limited measures seem to have become what many observers feared: pageantry in the face of public scrutiny, rather than a meaningful commitment to improving migrant worker conditions.

Full response of Qatar, SC and FIFA here.