Stories of Origin is a series that explores the lived experiences of both returning and potential migrants and their families. This is the second of a three-part piece on migrant fishermen from southern India. In the first part we spoke to families left behind in a village in the deep south of India.

In 2014, Sashikumar and his crew were detained by Iran when their Qatar-licensed boat crossed the border. For three months they were stranded in the Kish island. Migrant-Rights.org advocated for their release and helped repatriate them.

It’s been 18 months since his release when we sit down with his wife, Sheela, in a tiny house down a narrow street lined with stacks of drying fish. When we last spoke to Sashikumar, on his release, he and Sheela were expecting their first child.

A teary-eyed Sheela explains the stress of those months resulted in a still birth. “After 10 years I finally got pregnant… and then.”

Sashi’s story is not a strange one for the village. He first went to Qatar 20 years ago to secure a future for his family. To get his sisters married first, and then to set up his own family.

Sakunthala, of the NGO National Domestic Workers Federation (NDWF), works with the families of fish workers. She says the women of the community were all highly educated, unlike the men. Yet, they preferred to marry within the community. Huge dowries are doled out by the women, and the men in turn promise a lifestyle that they can ill-afford.

Father Churchill agrees. “These men who stay out for long periods of time indulge their wives, build comfortable homes; the few days they are on shore they want to experience luxury that offsets their trials in the rough seas.”

That’s just one minor reason why 60% of men in the Kanyakumari district migrate, Sakunthala says. “Only then (when they migrate) is there any economic development. They have to fend for themselves, as the government provides no support. Fishing yields just Rs150-200 per day. From there (the GCC), they can send upto Rs. 30,000 to 40,000 a month.Good season even Rs100,000.”

Yet, there is very little awareness. “They don’t even carry passport copy with them. Families don’t have copies of their paper. When they are arrested on land in trouble it’s a struggle to get paperwork done.” Currently, the NDWF is conducting a campaign to educate fishermen and their families on this.

There are also attempts now to impart financial literacy to prevent fishermen from being trapped into circular migration just to pay off debts.

Sheela, a seamstress, supplements the family income. Would she prefer it if Sashi stayed back in India?

“He is traumatised. He owned a boat and was deep sea fishing when it broke and no one helped him. Finally as he clung to a raft, fighting for his life, a merchant navy ship rescued him. He is scared now to go to these seas,” she waves towards the ocean that we can hear but not see, beyond the walls of her house.

“Wait, I will give him a missed call and he will call back. He wants to talk to you. Ask him.”

The phone rings soon enough. An Iran number flashes across the screen. Months after he returned, in February 2015, he went abroad again. This time to Iran. A gentleman helped him when they were detained in Kish island, and offered him a job.

Husbands of Sheela (right) and Anthonyamma were employed in Qatar and arrested in Iran. The men had no choice but to re-migrate even after the ordeal.

Benjamin spent three months in detention in Iran. He feels there's no safe way of running the 'trade'.

Husbands of Sheela (right) and Anthonyamma were employed in Qatar and arrested in Iran. The men had no choice but to re-migrate even after the ordeal.

Kish, a resort and a jail

“It’s a ‘super’ island,” laughs Benjamin.

He was one of the Ajman detainees. His wife fills in the gaps of his narration, every time he paused to shake his head, as if to say ‘never again.’

He migrated to the Gulf only in July 2015 after paying rupees 35,000. He recounts the trauma they set sail to on 15 November.

“There were five boats, mine was owned by a Sharjah sponsor. We worked in Ajman. Other four had an Ajman kafeel. We used to go near Iran border often, because the Arabi gets angry by our low catch, and would push us.

“We were all anchored in an island off UAE coast due to high winds. During that time the captain of one of the other boats told us that his kafeel had paid the coast guards. So we all went into Iranian waters. That’s where the trade is really good. Good harvest of fish,” he says, and explains how the crew functions at sea.

The captain remains on the boat. Every boat has about three rafts. The crew usually get on the rafts, with their nets, to look for a catch. Once they get a good enough catch, the nets are pulled on to the boat. The captain and the crew communicate on wireless.

On 1 December they set out to fish.

“Our captain contacted us on the wireless and told us they were caught. He asked us to cut the nets and run away. The coast guard managed to catch up. They caught 49 of us then. We were on 8 boats. Three escaped.”

So the coast guards were not bribed?

“I don’t think it’s true that the CG was bribed. It was more to encourage us to go without fear.”

For three long months he and his compatriots survived on bare rations, living on their boats anchored off Kish island.

Unnecessary criminalisation

Given the geopolitics of the Gulf region, fishermen being arrested is never just about crossing borders.

“During this time, an Iran launch was caught with ganja in UAE. Iran negotiated, asking UAE to release that boat in exchange for the 5 boats we were on. Dubai said nothing could be done as this was a ganja case. We were told we couldn’t depend on negotiation and sought the help of the embassy through Sister Valarmathi (of NDWF).”

On 3 March, he and the 48 other Indians were repatriated.

Sister Valarmathi’s rough estimate is that around 70-80 fishermen have been arrested so far in 2016 alone, of whom about 10-15 still await release or resolution.

Father Churchill bemoans the lack of influence Indian embassies have in the countries of destination. “How can workers land in a country and the embassy there not even be aware. When fishermen go missing the government doesn’t even know until we write to them. When fishermen are arrested or detained in neighbouring countries, it is not reported to Indian authorities. Captain doesn’t want to inform them. They prefer going to the sponsor directly. Neither they (the Embassy) respect Indians, nor are they respected by others.”

He also feels strongly that fishermen, even if they cross borders, should not be criminalised. “And when you do find a fisherman violating your borders you need to have a speedy trial. They cannot afford to be arrested and without an earning for weeks and months, as they don’t receive a set salary.”

He understands that the GCC states and Iran wish to guard their stock either for conservation or economic reasons, and hence suggests: “Countries in the GCC need to have a treaty on this, on the lines of IOTC which will extend some protection to fishermen.”

He also feels that the Indian government should be involved in it in some capacity as its citizens are in the crosshairs.

Benjamin says they can’t go to work depending on the ‘Dubai’ seas alone. The problem is, even if the catch is good in Iran, the economy isn’t. Everyone comes to UAE to sell the fish.

[tweetable]“We didn’t realise the risks before going to Dubai. Having gone there, we had no choice [/tweetable] but to work at all costs. The travel agents play the role of recruitment agents and send people without any proper training.”

He accepts that each person has a different experience. The more seasoned kafeels with larger fleets have better practices, he says.

Would you like to go back?

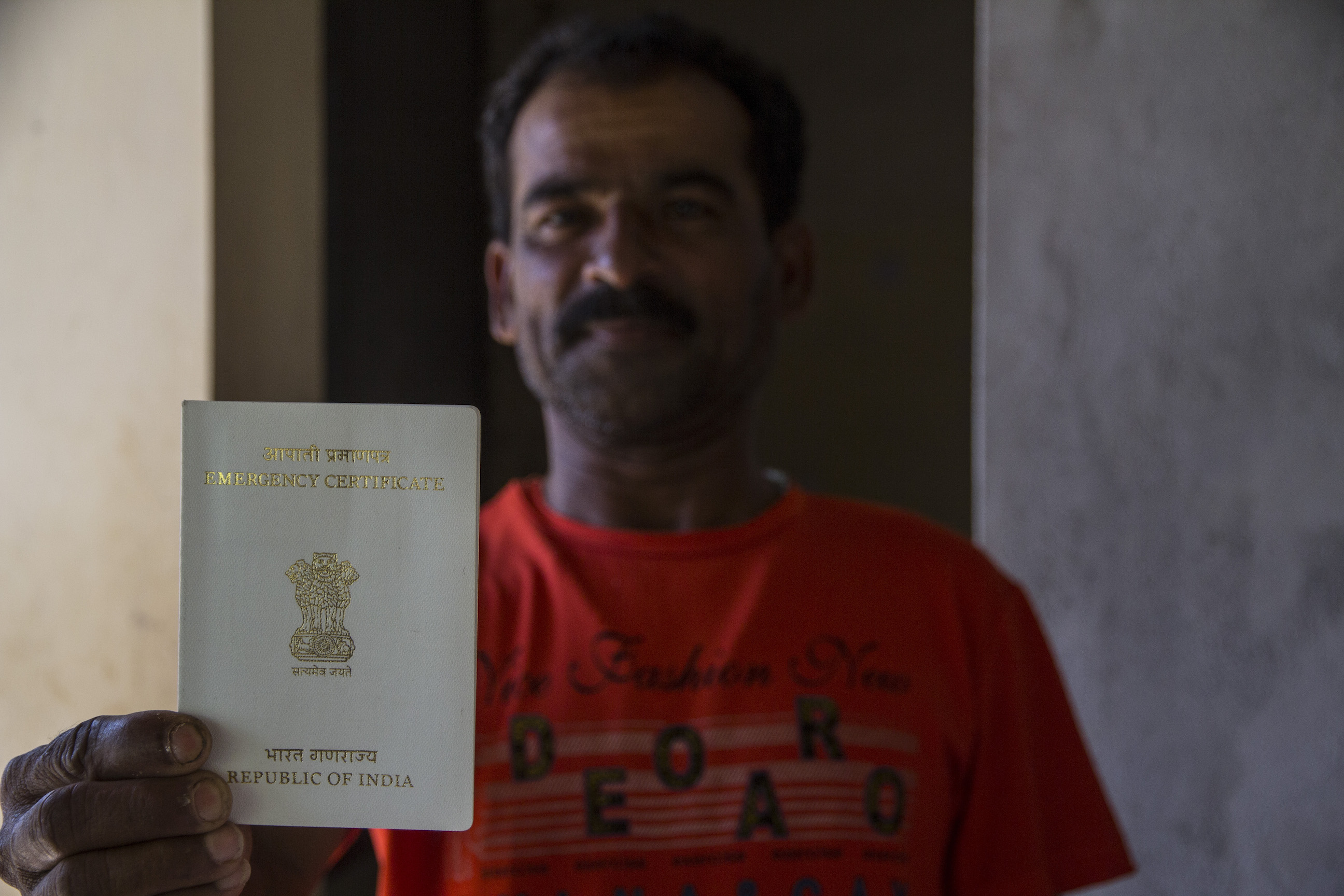

“No. I don’t even have a passport. Only the white passport,” he holds up the emergency, bleached version of the blue Indian passport.

![Image relating to [Stories of Origin] High skills, low value: Indifferent Governments on both ends of migration](https://www.migrant-rights.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/harb2-1024x683-310x200.jpg)

![Image relating to [Stories of Origin] Life after arrests](https://www.migrant-rights.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/benj1-1024x683-1-1024x460.jpg)