USD10 billion-worth unauthorized recruitment transactions in 10 years – ILO White Paper

A new ILO white paper – Ways forward in recruitment of low skilled migrant workers in the Asia Arab State corridor – says the recruitment fees paid by workers pre-departure should be viewed as “an ‘extortion’ that has become an acceptable institutionalized business norm in the labour recruitment industry.”

The paper estimates that in the past decade, unauthorized cash transactions have amounted to around US$10billion. “Assuming that the total number of foreign nationals in the GCC workforce is around 13 million and 80 per cent (around 10 million) are from Asian countries where workers pay private recruitment agencies; and assuming each worker pays an average of US$1,000 over and above the actual costs…”

With such huge stakes, it’s little wonder that recruitment agencies in countries of origin push back against any kind of regulation that will limit their ability to extort.

The paper is authored by Dr Ray Jureidini, professor in migration, ethics and human rights at the Center for Islamic Legislation and Ethics (CILE) in the Qatar Faculty of Islamic Studies, Hamad Bin Khalifa University, Doha.

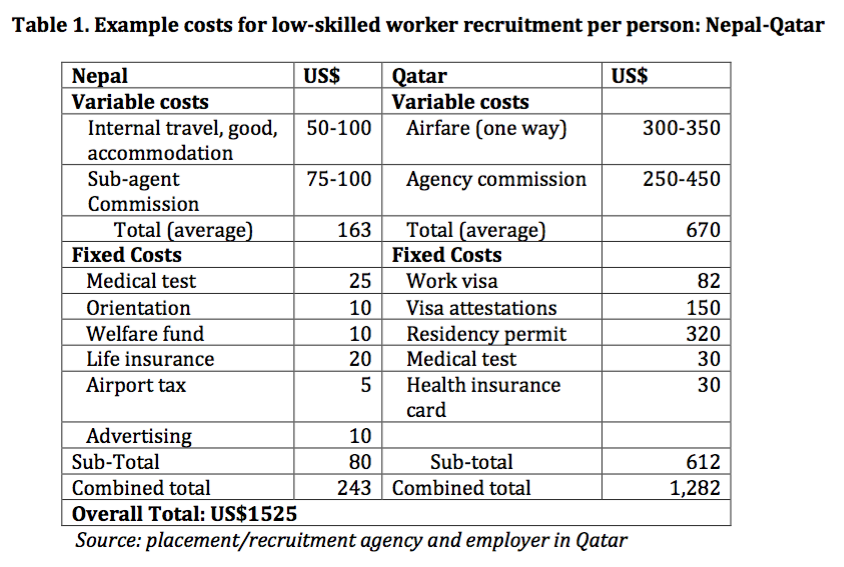

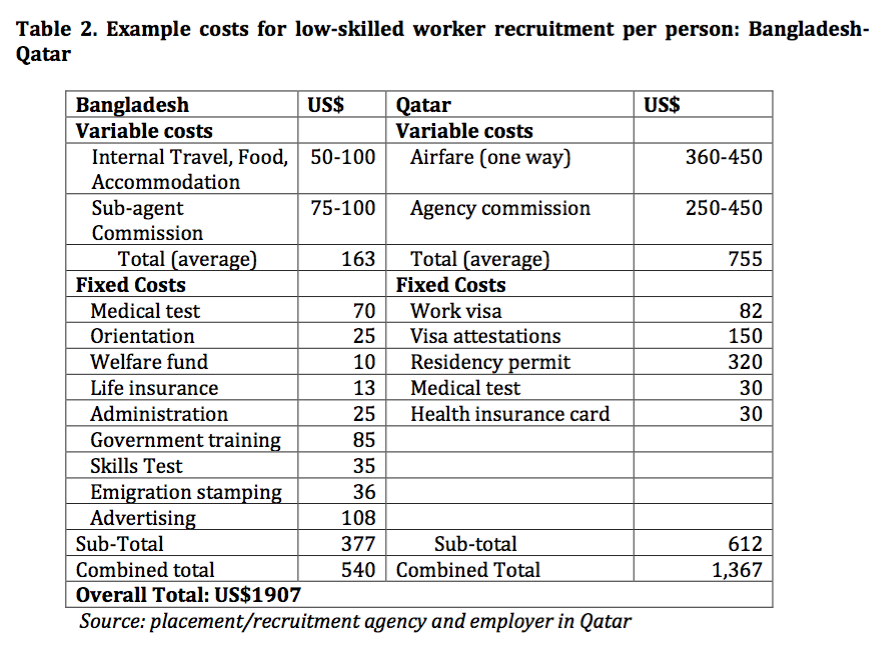

He writes that employers of higher skilled workers cover all recruitment costs, but “lower skilled migrant workers in construction, agriculture and services (including domestic work) pay agencies between US$500 to $5,000, or equivalent to between 1 to 15 months of their earnings abroad.”

And, even when employers pay all recruitment fees and costs, “private recruitment agencies can still charge workers because workers expect to pay.”

The paper highlights some positive developments in the region and suggests a wider adoption of such regulations.

A standard contract has been recently developed by the UAE with extensive articulation of termination conditions.93 Along with new legislation that confers legal contractual status on the letter of offer before departure, the UAE initiative provides uniformity for both origin and destination countries that militates against illegal contract substitution. It is recommended that other Arab states and countries of origin make similar agreements regarding standardized contractual arrangements.

As for countries of origin:

The Philippines, Indonesia and Ethiopia are the only countries where national legislation forces recruitment agencies to be financially liable for any wage discrepancies between what was promised to the migrant worker and what was actually paid, although few migrant workers have the confidence to bring a lawsuit against an agency.

Some important excerpts from the white paper:

First, contractors and subcontractors “outsource” recruitment costs to private recruitment agencies in origin countries as a means to circumvent local labour laws that prohibit workers paying recruitment fees. Second, employing companies save money and increase their competitiveness by not paying for recruitment costs. Third, private recruitment agencies compete internally and internationally to obtain labour supply contracts by providing kickback payments to employing company personnel and placement agencies in the destination countries. The costs of this collusion between the private recruitment agencies, employing companies and placement agencies are passed onto low skilled workers.

Despite local labour laws in Qatar,the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and the UAE that prohibit charging fees to workers, these laws have sometimes been interpreted by employers and recruitment agencies as a prohibition of the deduction of wages for recruitment fees in the destination country. Thus, the fees are taken prior to departure in the origin countries. The exception is the UAE, where the law includes the prohibition of accepting or demanding payment from workers “whether before or after recruitment” (Article 18 of UAE Labour Law No. 8, 1980). ILO Convention 181 (Article 7) stipulates clearly that workers should not pay recruitment fees or costs anywhere.

Project tenders should include a separate detailed transparent ‘Labour Recruitment Cost Analysis’ within the bidding proposal that details variable and fixed costs of recruitment, including labour costs of subcontractors.

Complying with this recommendation would ensure that the intention of tenderers and their subcontractors is to pay for all recruitment fees and costs related to labour, accommodation, recruitment, and training. Labour cost details may be an intermediary step introduced between the technical and commercial evaluation phases, or along with the commercial evaluation. Clearly, labour recruitment costs should not be calculated after a tender has been awarded. If properly documented and audited, unfair recruitment can be more easily detected before the projects are awarded.

Although countries of destination often assume they have no jurisdiction over recruitment practices in labour origin countries, they can demand that fair and ethical requirements are met through the joint liability approach. They can insist that the contract of employment meets the minimum standards, complies with terms agreed upon, protects the employee and includes provisions on the ability to change employer. Joint liability through bilateral agreements should also focus on combating contract substitution and other inconsistencies and that the minimum standards are understood by employers and recruiters on both sides of the migration corridor. Joint liability practices rely heavily on inter governmental cooperation and require commitment from countries of origin and countries of destination equally.