UAE turns a blind eye to rampant abuse of its visit visa; employer-pays model only on paper

With Covid-19-related restrictions on formal recruitment, more and more Nepali migrant workers are going to the UAE on visit visas. Though technically legal under UAE law, Nepal’s government bans workers from travelling on visit visas for the purposes of employment. These migrants often end up paying extortionately high fees for non-existent jobs, with none of the legal protections formally recruited workers are entitled to.

Rabin Naharki, 23, was a bus helper on the Kathmandu-Pokhara route. Before the pandemic snatched his job, Naharki used to save NPR30,000 (approximately US$255) monthly.

His earnings plunged with the outbreak of Covid-19.

“Earning money is possible only when the bus is fully packed with passengers,” said Naharki. “Driving an empty bus doesn’t make money. We need to pay NPR7,000 (US$59) daily to the bus owner. The boss won’t agree to less than that.” Hit hard by the Covid-19 crisis, his employer sold the bus.

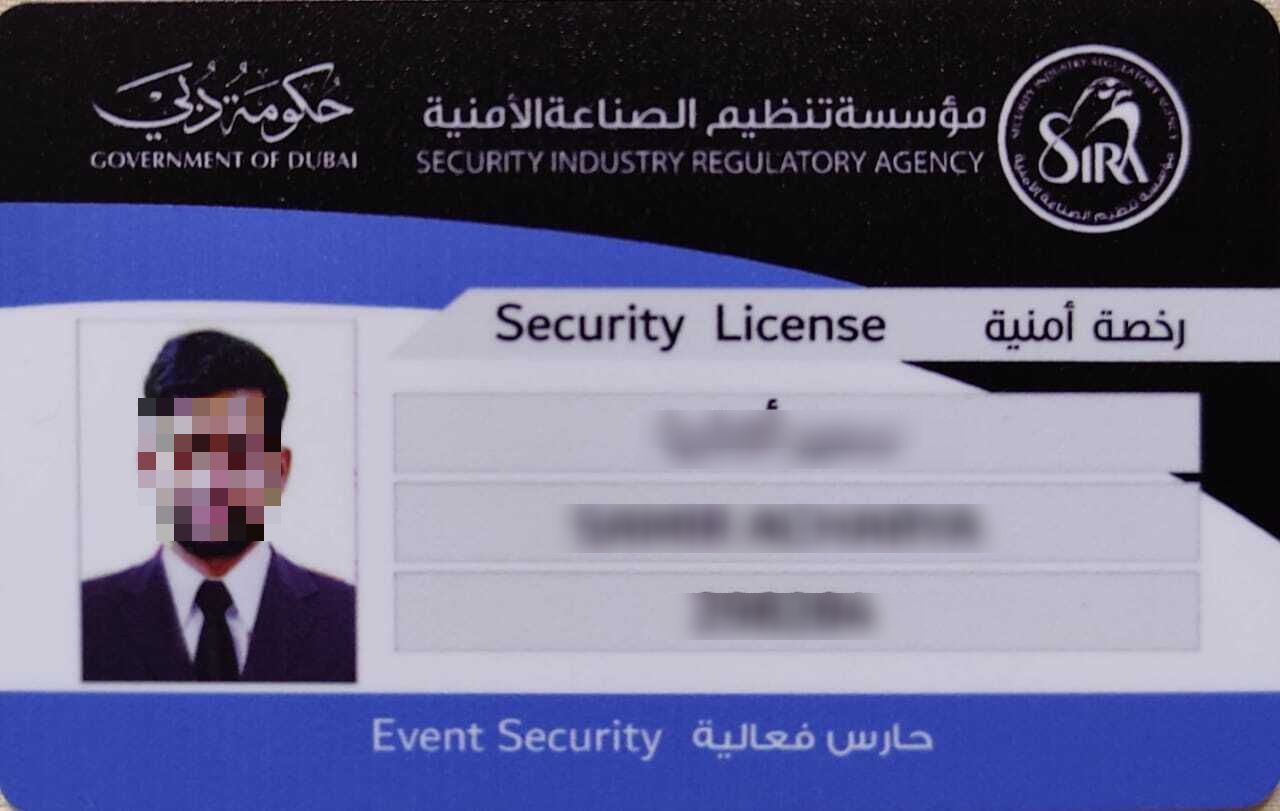

Workers tricked into migrating on a visit visa after paying huge fees, at their accommodation in the UAE (see box below for full story)

Frustrated by the work, he didn’t want to seek another job in the transportation sector. Instead, he set his sights on the UAE. He travelled to Kathmandu, where his sister, who works for a health institution that conducts medical examinations for aspiring migrant workers, helped him get shortlisted for a job. “It’s easier if you have connections. My company has also been finalised, so I’m waiting for an offer letter. I will fly by the end of September,” Nakharki said.

A cleaning company has hired him for a basic salary of AED800 (US$220), and he can earn double wages if he works holidays.

“With tips and overtime, I will earn AED1800. I'm told that I don’t even have to do my own laundry, cook food or work outside. I’ll work in air-conditioned areas. I like this company.”

He seems genuinely excited, but also increasingly wary.

His recruitment agency is now seeking NPR150,000 (US$1278) from him. “The manpower staff told me that the situation is different from what it was earlier, the flight price had been hiked. Because of this, my sister gave me a NPR15,000 discount. I need to pay the rest once my visa is confirmed.”

Naharki borrowed the sum from a money lender. “I will have to pay nine percent interest. I think I will settle my loan in six months, and what I earn during the remaining 14 months will be my savings.”

He declined to divulge the names of either the agency or the cleaning company. “It’s a well-known company. What will happen if I disclose the company name? If the company is defamed, my visa might be cancelled. I will be jobless again.”

Under the labour agreement signed between Nepal and UAE, migrant workers should not pay any recruitment fees. “The labour agreement signed with the UAE respects the employer-pays model,” Gokarna Bista, Nepal’s former labour, employment, and social security minister, stressed. “Employers are fully responsible to abide by the agreement.” (see box)

The reality is far more complicated than the agreement states. Nepali migrants workers are paying hefty fees of NPR150,000 and above. Workers Migrant-Rights.org spoke to say they are willing to pay up to NPR700,000 (US$5950) for jobs as security guards.

Bista admits that migrants are paying increasingly high fees for jobs in the UAE, but what they are promised at home is not what they ultimately receive on arrival as contract substitution is rife, even with checks in place. In a recent example, the Department of Foreign Employment permitted Kalinchowk Manpower Company to recruit workers to EFS Facilities Services based on EFS’ proposal to pay a minimum of AED900. But the offer letter handed over to migrant workers (and reviewed by MR) indicates their basic monthly salary is just AED600.

Recruitment agents in Nepal say most UAE companies have started to charge them a fee for job orders. “They won’t give a work demand letter without us paying AED1500. They aren’t covering flight costs either,” said Rohan Gurung, former president of the Nepal Association of Foreign Employment Agencies. “Workers need to bear these expenses.”

Visit Visa: yet another trap

Though demand for workers is high, migration to the UAE remains restricted. In the aftermath of Covid-19, the UAE limited new work visas to primarily government and semi-government companies, excluding most private companies. According to the Nepali Embassy in Abu Dhabi, government and semi-governmental companies have sought verification of demand letters for 30,000 workers. So far, work permits have only been issued for around 8,500 applicants.

To meet demand, UAE companies have started to recruit locally from migrants seeking to change jobs or those in the country on a visit visa. As a result, Nepali migrant workers have started to travel to the UAE on visit visas in hopes of finding a job and converting it to a work visa. Their recruitment expenses consequently rise exponentially, not to mention the risks involved. While the UAE does allow conversion of visit visas to work visas, Nepal views this mode of migration as irregular and excludes visit visa migrants from the minimal protections their missions extend to workers abroad.

Rajan Prasad Shrestha, executive director of the Foreign Employment Board, said workers going abroad on visit visas will not be able to access any facilities or safeguards provided by Nepal’s migration law.

“If workers going abroad on visit visas are deprived of getting stated salaries and facilities, manpower companies will face action. Deposits posted by manpower companies will be used to reimburse migrant workers’ expenses,” he added. Earlier this year, the Department of Foreign Employment caught two agencies – Nepal Manpower Pvt. Ltd. and Reliance HR Manpower – charging migrants exorbitant fees for visit visas to the UAE. One of the directors was sentenced to one year and six months imprisonment, and fined NPR25,000 by the Foreign Employment Tribunal.

But while some agencies may face penalties, the workers who are hoodwinked remain excluded from protections.

Those migrating on formal labour permits are registered in a welfare fund. The government bears treatment expenses in case of injuries or serious illness, and ensures legal support if needed. The insurance provides up to NPR1.7 million in case of death, and children receive a scholarship up to high school. None of these safeguards are extended to those who migrate on visit visas, even if they later manage to change their status to a work visa.

Nirmala Thapa, an embassy official in UAE, said Nepali migrant workers on visit visas have started to approach the embassy for help. “Those who arrived here on a visit visa are unskilled workers. They cannot compete in the labour market nor can they begin legal cases."

She said the Nepali embassy is holding discussions with large companies to make the recruitment process more transparent.

According to Nepal Association of Foreign Employment Agencies General Secretary Sujit Kumar Shrestha, “At least 50,000 migrant workers have entered the UAE using visit visas. This may benefit the UAE government and companies, but it has caused a huge economic burden for Nepali workers.”

Shrestha said he does not understand why the UAE is not issuing work visas directly as it is, in any case, converting visit visas into work visas once the workers land.

– By Hom Karki

A five-month ordeal |

|

When 25-year-old Rajendra K* flew to the United Arab Emirates (UAE) in March 2021, he dreamt of earning enough money to support his middle-class family living in the Saptari district of Nepal’s southern plain. But five months later, he returned home empty-handed. “I couldn’t even pay back my loan, let alone earn something,” says Rajendra, who had planned to work as a security guard. Instead, he is now stuck with a debt of NPR400,000 (USD$3400). The UAE is the second major destination country, after Qatar, for Nepali workers, according to the 2020 Labor Migration Report by Nepal’s Department of Foreign Employment (DOFE). And about 10% of them are recruited for the security sector. The pandemic put paid to the dreams of many as the UAE paused employment visas for migrant workers in March 2021. But by exploiting the UAE’s visit visa provisions, recruitment agencies in Nepal have continued sending workers to the Gulf country. Agencies, like Link Star Manpower Services Pvt. Ltd. in Kathmandu, lure aspiring migrants with false promises of foreign employment. “Link Star agents promised us jobs as security guards and said the visa type doesn’t affect us. We trusted them,” said Rajendra. Unemployed and desperate for work, Tejendra and his four friends paid NPR250,000 (USD$2,150) each to the agents. Link Star then arranged their paperwork – invitation/sponsorship letter, travel insurance, hotel booking, PCR tests and flights. “We later realised the visit visa doesn’t allow us to work – they (agents) cheated us.” Harka Mani Rai, counsel director of Link Star Manpower, admitted that his company had sent ‘some’ youth for foreign employment on tourist visas. “Our brothers had sent some youths, but we sorted out their cases as the problems occurred,” he said over the phone. Before travelling to the UAE, Link Star agents told them that they would be employed by BDS Security Services and earn AED2260 monthly. “Upon arrival at the Dubai International Airport, our dark days began,” said Satish, one of the four friends who migrated with Rajendra. Satish is still in Dubai. In a series of phone calls from Dubai, Satish and his four friends spoke of hardships, threats, abuses, and slave-like living conditions. He says a Link Star agent – who introduced himself as ‘Sultan’ from Pakistan – picked them up from the airport and took them to a cramped, dusty dormitory in Deira where they stayed for two weeks. “We fifteen people would stay together and sleep on metal bunk beds,” he added. “We hardly had any food to eat and no money to buy more.” None of them was vaccinated. ‘Sultan’ would threaten them not to go outside without his permission, confiscated their passports, and collected US$1,000 from each. For about three weeks, ‘Sultan’ frequently moved them to different places, saying he would put them to work at security companies. “Looking for jobs, we wandered so many places with him,” Satish recalled. “We spent some nights on the streets on an empty belly.” A month after arriving in Dubai, they ran out of money and requested food support from other Nepali worker. While living in a shabby dorm and sustaining themselves on charity, Suraj – another migrant worker from Nepal’s Sunsari district who is now back home – became ill but couldn’t go to the hospital. “I couldn’t even get treatment because I didn’t have health insurance. Nor did I have money,” Suraj said. Fake documents, illegal work Documents obtained by Migrant-Rrights.org indicate that Link Star Manpower and its UAE-based agent then forced the youngsters to work illegally with fake documents. The documents revealed that ‘Sultan’ provided them with fake Security Industry Regulatory Agency (SIRA) licenses. SIRA is a UAE government agency that trains and issues security guard licenses. “We haven’t done any tests or training for the security guards (licenses), but he (Sultan) brought them to us to our room,” Satish said. Sultan had also given them the fake identity cards inscribed with the Bab Al Dahabi Security Services’ logo. Under immense pressure from ‘Sultan’ and Link Star, the five youths worked for a week at Hawk Security Services in Sonapur, according to Suraj. When a month later, the manager discovered they were working under fake ID cards, they were kicked out. Suraj says they also worked at Group-2 Securities in Deira for a few days, but were kicked out again when their two-month visit visa expired in May. None of them received payment for the days they worked. In an audio clip, Group-2 Securities staff are heard saying, “we cannot deploy the ones whose visas already expired…problems will occur later.” Still, Link Star Manpower agents continued to force them to work illegally. In an audio recording of a telephone conversation obtained by MR Harka Mani Rai, of Link Star Manpower, is heard telling the youth, “Do your duty. I won’t do anything for you if you stop working”. Amid immense pressure from the manpower agents and their financial obligations, Suraj says they worked illegally for around two more weeks, but never got paid. Sliver of hope Stranded in Dubai for five months and with expired visas, they asked for help from many people and agencies in Nepal and UAE time and again. Satish sent emails asking for help from the Nepali embassy in UAE, the Nepal Police and its Anti-Human Trafficking Bureau, the Central Investigation Bureau, the Department of Foreign Employment and the Labour Ministry. Nirmala Thapa, the embassy labour counsellor, responded to the email, not offering help, but advising the complainants to “be conscious on time and try to follow legal channels.” The Anti-Human Trafficking Bureau staff suggested they file a written complaint, but did not indicate whether they had begun an investigation based on his plea. None of the others contacted responded. With little hope of support from authorities, the workers posted videos on Facebook in June, begging for help. After the months-long painful struggle, two of them managed to find jobs and convert their visas. Three others returned to Nepal in debt. “After five months, we’ve managed to get out from the nightmare,” said Satish, “But there are other Nepali youths here (in UAE) who have no one to help.” *All names changed By Pramod Acharya |