Back in 2013, Kuwaiti authorities announced for the first time their “experiment” to segregate hospitals in order to “decrease pressure on health facilities.” During those three years, the health ministry, with the help of media, popularized a discourse to support their claims; in the past year, many networks and newspapers created polls to depict the project as democratic and supported by most citizens. This included blaming expats, who make up two-thirds of the population, for long waits in hospitals and clinics. The media blamed migrants, despite the fact that Kuwait’s parliament and politicians have publicly and regularly criticized the government for failing to reform or meaningfully expand health services since the 1970's – with the exception of under-construction Jaber hospital, which will be “for Kuwaitis Only.”

Kuwait’s Health Minister Dr. Ali al-Obaidi, a doctor and a graduate of the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland, continues to deny the discriminatory nature of the new project. Though he stressed in a TV interview that the new hospital would only be for citizens, he argues segregation is only a "regulatory measure” that aims to “offer best care for Kuwaitis.”

The latest update on the segregation project came earlier this month when the Fatwa and Legislative department approved a plan to “set an independent health care system for expats.” State discourse manipulates the true nature of this project, calling the segregated health system merely “independent.” The plan is to establish a public shareholding company named the Health Insurance Hospital Company, comprising of a partnership between the managing company and investor, the state of Kuwait, and citizen shareholders. This company will build health facilities from scratch which, according to Kuwaiti authorities, would be responsible for the country’s 1.8 million migrants (which is in actuality, closer to 3 million) – a disastrous plan that we refute here in detail.

Previous and Proposed Healthcare Reforms

[tweetable] In 1999, Kuwait terminated free healthcare for non-Kuwaitis, including both the expatriate and stateless population of the country.[/tweetable] Back then, there was no private healthcare sector so non-Kuwaitis were charged per visit and for each test or surgery. In 2006, expatriates were required to purchase annual health care plans for KD 50 in order to renew their residency permits. However, this cost covers no medical services, and expatriates still had to pay for every visit, test, surgery, and medication.

The plan to segregate health services was first introduced as an “experiment” in June 2013, when Jahra hospital reserved morning visits exclusively for citizens “when all staff is available.” Expats could only visit in the evening, though citizens were allowed to come in at any time. The experiment then expanded to three hospitals and 15 clinics, with “priority for Kuwaitis” signs posted. Some medics and NGOs were critical of the decision, but their voices were lost among the masses and the complicit role of local media.

In reality, the new plan does not aim to serve citizens or regulate expats, but rather to “activate the partnership between private and public sectors,” according to a statement made by the health minister made earlier this month. When this project is implemented, expats’ health insurance will see a 200% surge, tripling to not less than KD 150 (490$)- for a basic plan which does not include advanced care.

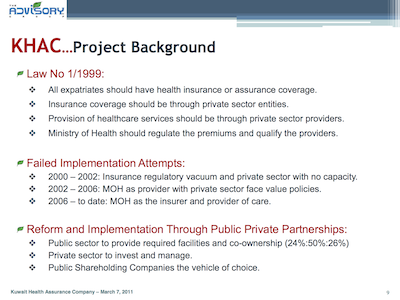

During this investigation, Migrant-Rights.org obtained a copy of the draft proposal made by “The Advisory Group Management Ltd” (TAG), a private company managed by Ahmed M. Nsouli and Juliana M. Shawa (who both have profiles on the Panama offshore leaks). The company’s website is “under construction” but describes itself as a “regional healthcare consulting company on its Linkedin page. Being the ‘first and most experienced healthcare consulting firm in the region’, TAG is a ‘boutique’ firm which does not have a website, does very little marketing, and works by referral only.” In November 2012, TAG sponsored a three-day fair named “Future Health” to promote its project, asking the medical community to “capitalize on Kuwait’s healthcare delivery and infrastructure projects.” The program included a keynote by a “senior representative” from the Health Ministry.

TAG proposed to establish “an integrated, for-profit, world-class health system to manage the care of [the] vast majority of expatriates in Kuwait.” According to the leaked proposal, the “Health Insurance Hospital Company” was originally named “Kuwait Assurance Company – KHAC.” At KWD 318 million ($1055 million), the company would be the largest public offering in Kuwait’s history, “developing and selling its own health plans to target market.”

KHAC Executive Brief Presentation 07-03-2011 divides expats into six categories: 1) dependent of Kuwaitis 2) Stateless 3) public sector employees 4) agriculture and fisheries workers 5) domestic workers 6) all others expats. TAG locates the sixth category as the target group, accounting for 62% of expats (1.5 m) which leaves the other categories out of the plan. TAG hopes that this company will become “a new model that will be emulated throughout the region.”

According to this plan, the company estimates its eligible market size to be 1,832,937 KD in 2017 and 2,236,959 KD in 2024. The capital needed for this company was proposed at 349 million KD. The income expected is between 28 million in 2017 and 72 million in 2023. The state would lease three land plots to the company’s hospitals. The annual “premium” rates charged to expats will be 150 KD in 2017, and will increase to 190 in 2023. Those rates are subject to increases if inflation rates exceed 6%. Health plans will be automatically linked to residency renewal.

But what would those services really offer? The plan proposes three hospitals in three different regions, with a bed capacity of 240, 712, and 340. This accounts to 1292 beds for 1.5 million expats (the target market) or an estimated 2-6 beds for every 10,000 expats. Those facilities will employ 648 physicians and 2919 technicians and nurses. While bed capacity may not necessarily reflect services offered, this number is far below the 2.92 global average. Further, Kuwaiti medics opposed to the project note the new facilities will not offer surgeries, treatment for chronic diseases, therapy for mental issues, or medication, without extra charge.

Kuwaiti Doctors Criticize the Plan

Back in 2011, a group of Kuwaiti doctors under the name of The Health Care Reform Advisory Group (HCRAG) were the first to reveal this project. They tried to organize public talks and discussions, asking experts and journalists to speak against the project, which is “doomed to failure.” The group is no longer active and their website (http://www.q8health.org/health-reform/) is no longer accessible. However, Migrant-Rights.org previously obtained a statement from the group when the project was still a proposal:

"Kuwait's plan to create a separate health system for expatriates will introduce a physical barrier to the already existing behavioral and financial obstacles suffered by the nation's most destitute populations. Evidently, this concept does not stem from existing health policy evidence. Rather it has been formulated by policy-makers seeking a rapid, "band-aid" solution to the nationals' concerns over overcrowding in healthcare facilities. Segregation of health services is already seen in Kuwait. Separations are enforced in primary care clinics and in certain intensive care units. The proposed for-profit health maintenance organization (HMO) also introduces an unsuccessful model based on the free market approach. In our poorly regulated environment, and based on past experience with healthcare privatization, we anticipate abuses, which will further negatively impact the customers of this system. Contrary to the way this has been marketed by its proponents, this scheme is in obvious violation of basic human rights, is not financially viable, and will not result in high quality services. Our group, the Health Care Reform Advisory Group (HCRAG), proposes an alternative, more comprehensive and equitable reform agenda endorsed by international experts and based on global evidence and recommendations by leading health agencies."

The exclusion from essential social services is just one among many of Kuwait’s attempts to squeeze the most profit out of its expatriate labour, while providing few rights and protections. The Minister of Electricity and Water recently said expats will not be given the “privilege” (reserved for citizens) to pay their overdue bills in installments; those who fail to pay in full will have their services disconnected immediately. In the past few years, Kuwaiti municipality have ensured that expats are unable to rent housing from Kuwaitis under the banner of “protecting morality and family values,” while in reality striving for profits in the real estate sector; migrants often rent from homeowners because these houses are usually rent-stabilized, more affordable, and closer to their work areas than the ‘bachelor’ apartment buildings marketed by real estate developers.

Further, the Minister of Labor and Social Affairs Hind al-Subaih promises to limit the residency period allowed for expat, and parliament members have proposed a plan to tax expats. Kuwait’s deportation campaigns registered the most extreme measures in recent years, with migrants deported for political statements, traffic violations, barbecuing in public, harassment, and other absurd reasons. Just this month, the Ministry of Interior said it will not renew the residencies of 100,000 domestic workers who hold driving licences “as they cause traffic.” Kuwait’s migration management is unabashedly shifting from a system that lends to migrant’s exploitation, to a system that very directly exacts this exploitation, capitalizing on their income and wellness.