On September 2017, the Labour Market Regulatory Authority (LMRA) announced that all recruitment agencies in Bahrain must adopt a new mandatory contract for domestic workers from 1 October 2017 onwards. Under the new contract, employers seeking to hire a domestic worker must declare, among other things, the nature of the job, work and rest hours and weekly days off.

While Bahrain is the last GCC country save Oman to implement a standard contract, it was the first and only country in the region to partially incorporate domestic workers into its labour law.

Still, Bahrain’s regulations do not comply with the International Labour Organisation’s (ILO) domestic worker standards. Domestic workers remain excluded from critical protections, such as a fixed minimum wage, limits on working hours, mandatory rest hours or weekly days off. Domestic workers are particularly vulnerable to excessive working hours, with many working up to 19-hours a day and with no rest day.

The LMRA’s chief executive hailed the new contract as a “radical” solution to address the abusive practices domestic workers face. But while the contract clarifies some obligations of employers and recruitment agents, it falls short of giving domestic workers fair and equal legal protection.

According to the latest available figures, the total number of domestic workers in Bahrain in 2017 reached 100,058, of which 76,249 are women.

New contract requires employers to clarify working conditions

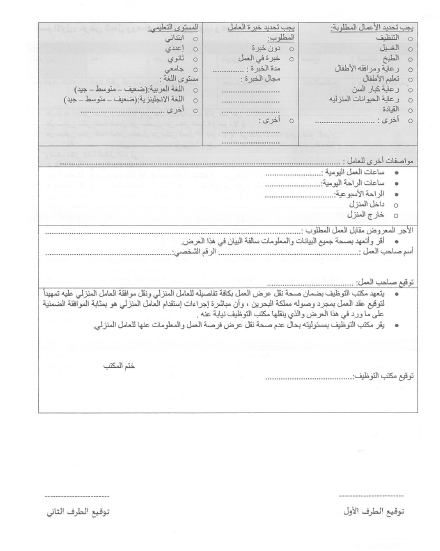

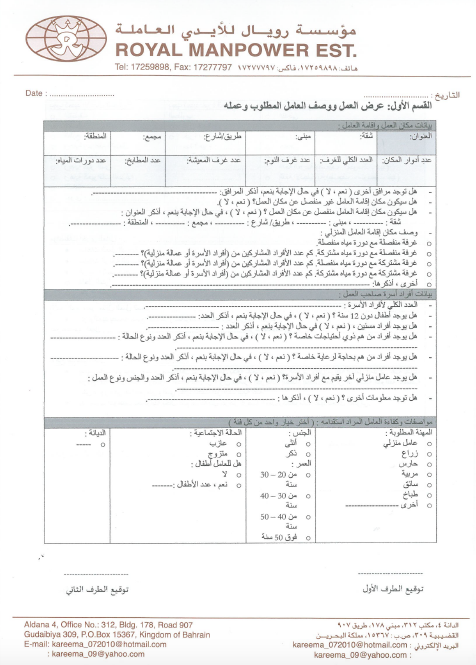

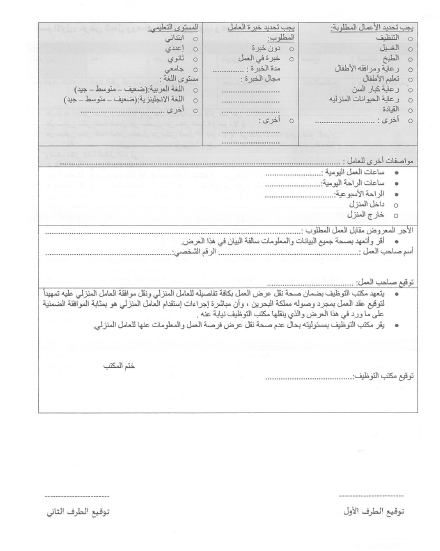

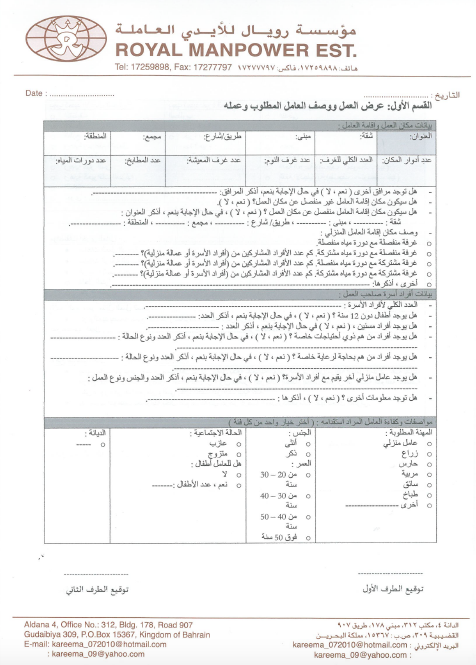

The first section of the contract specifies the number of daily working and rest hours, and weekly off day, whether the day off is spent indoors or out, and wages. It also includes details of the employer’s residence, information about the employer’s family members, and the nature of the job – such as whether it involves cleaning, cooking or caring for elderly people.

A template of the first section of the new domestic worker contract received from a recruitment agency In Bahrain

A template of the first section of the new domestic worker contract received from a recruitment agency In Bahrain

A template of the first section of the new domestic worker contract received from a recruitment agency In Bahrain

A template of the first section of the new domestic worker contract received from a recruitment agency In Bahrain

When the employer has filled out the first section of the contract, the recruitment agency then sends the details to a designated domestic worker or to an affiliated agency abroad, where the worker can then reject or accept the job contract while still in his or her home country. This is a positive step towards ensuring domestic workers are aware of the nature of the work, the living and working environment, and their salary.

However, the responsibility to translate the contract and inform the domestic worker of all details of the job offer lies solely with the recruitment agencies, still leaving opportunity to misinform and deceive the domestic workers about the terms and conditions of the job.

More transparency, but no new protections

The new contract does not lay out any new mandatory working conditions. It remains up to the employer to determine the working hours, minimum wage, and rest time – factors which should be regulated by law. The absence of a maximum working hours mandatory rest time is a gross diversion from the provisions of part seven of Bahrain’s labour law, which does not apply to domestic workers, which stipulates a maximum daily limit of eight working hours.

Domestic workers are slated to be included in the recently announced Wage Protection System, which will be implemented gradually starting in May 2018.

Enforcement Mechanism needed

The primary value of the unified contract is therefore in informing prospective workers of the conditions they are to expect, a hugely important step in reducing recruitment deception, contract substitution, and exploitation. However, the lack of enforcement mechanisms renders the purpose of the contact largely ineffective. Inspectors have no real authority to inspect private homes, and the contract doesn’t fall under the provisions of Bahrain’s labour law on Labour Inspection and Judicial Powers.

Part Sixteen Labour Inspection and Judicial Powers

Article (177): Officers who are delegated by the Minister to undertake inspection duties and ensure the enforcement of the provisions of this Law and orders issued for its implementation shall have access to the worksites, examine the records related to workers and seek the necessary information, data and documents to undertake inspection duties.

Enforcement mechanisms are essential, considering that domestic workers face many difficulties in self-reporting abuse or breach of contract. Most of them are confined to their employers’ homes (which the contract permits) and fear retaliation by the employer. Language barriers and lack of knowledge about workers’ rights and laws further restrict their ability to report abuse.

Karim Radhi of the General Federation of Bahrain Trade Unions (GFBTU) also called for “stronger implementation measures including monitoring of places where domestic workers are employed. “

While the unified contract is a step forward unless the limitations outlined above are addressed it remains more than an unenforceable job offer than any “radical” solution to the situation of the domestic workers in Bahrain.