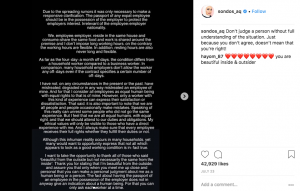

Blogger Sondos Alqattan’s blase tirade against basic rights for domestic workers is the latest video to go viral from Kuwait for the wrong reasons. The Instagram-celebrity posted her criticism of what she assumed was the Philippines’ ‘newly reinforced minimum standards’ such as a day off and right to retain one’s passport. In fact, these minimum standards are codified in the Kuwaiti law. Since her ill-informed rant, she’s been dropped by sponsors, banned from recruiting domestic workers by the Filipino government, and the subject of global censorship. All of which only resulted in her tapping into the publicity and releasing another video to defend her stand, in which she urges discussion of ‘more important issues like botox’ and offers no apology.

When your career is built on clicks, the line between fame and infamy is blurred, and any publicity is good publicity.

Last year, another video filmed by a Kuwaiti employer also attracted global condemnation. In this clip from Snapchat, the woman casually filmed Adesech Sadik, an Ethiopian woman working a domestic worker, clinging to a balcony with one hand without offering any support and then continued to film her after she fell. While the employer (who remains anonymous to this day) claimed that Sadik was attempting to commit suicide, Sadik later said she had been trying to escape the abusive household.

Both videos depict a kind of violence towards domestic workers that is pervasive; at the core of both videos is the casual dehumanisation migrant domestic workers endure in Kuwait, the wider Gulf region, and elsewhere in the world. While Sadik’s video illustrates a more direct effect of these attitudes towards domestic workers, Sondos’ debasing commentary similarly reflects a prevalent mentality which enables terrible acts to be committed towards domestic workers, often with little protest from family members or other observers of abuse. While ‘abuse’ is not limited to physical or sexual violence, Alqattan commentary was particularly chilling as they came just a few months following the discovery of Joanna Demafelis’ body in a freezer in Kuwait. Demafelis was a Filipina working as a domestic worker for a Lebanese-Syrian couple living in Kuwait.

Indeed, Sondos’ perspectives are outrageous because they are so widespread – her feelings are shared by other Kuwaitis, by Kuwaitis authorities, and by the Gulf states at large. Her arguments against a day off echo the GCC’s own condemnation of the Philippines’ minimum standards for domestic workers when it was originally promulgated in 2011. Saudi banned Filipino workers until relenting to the Philippines’ minimum requirements one year later. In 2014, the UAE launched a standard contract for domestic workers that prevented the Philippines embassy from being able to certify contracts and enforce their minimum standards. In 2013, a GCC-wide standard contract for domestic workers failed largely due to disagreements over a weekly day off; in 2014, the region-wide contract was again attempted, in part to circumvent ‘excessive demands from Asian countries’ like the Philippines.

Eventually, the GCC states relented to the Philippines’ minimum standards only because the demand for Filipino domestic workers – perceived to be higher skilled than domestic workers of other nationalities – is so high. Ironically, these beliefs that Filipino workers have superior skills do not translate into a greater valuation of their labour.

The very standards that seem to shock Sondos have been requirements in the standard contract for Filipino domestic workers and Kuwait’s own laws for years. Quite clearly, these standards have not been enforced, with many employers unaware, ambivalent, or, like Sondos, hostile to their existence. They are only now coming back into the spotlight due to a renewed commitment between the Philippines and Kuwait, following yet another viral video involving domestic workers in Kuwait.

In a phone interview to AFP, Alqattan said: “I have the right as a kafil (sponsor) to keep my employee’s passport, and I am responsible for paying a deposit of up to 1,500 dinars (around Dh17,998).” Her follow-up Instagram post which sought to “clarify rumours” echo this failure to understand that Kuwaiti law explicitly does not allow an employer to retain an employee’s passport. Alqattan’s (mis)understanding of the law is no doubt widely shared by other employers. (There are local efforts, in partnership with the government, to publicise the Domestic Workers Law.)

In her series of non-apologies, Alqattan blames Islamophobia for the public outrage against her comments, though many of her critics come from within the region. Sundos’ claims went viral largely due to her public persona, and she has received much condemnation from within Kuwait in particular. Kuwait stands out amongst its GCC counterparts in that it has a strong civil society that does raise issues of human rights, that speaks out against xenophobia and that criticises the government’s migration policies. But it has an equally loud counterpart with significant influence in government and local media. Sondos’ self-victimising concern with the cost of recruitment is one regularly repeated by members of the government. State-sanctioned xenophobia cannot be divorced from efforts to keep working conditions and remuneration especially low for domestic workers and other migrant workers.

Alqattan appears to embody the worst of the 1% tropes; a clearly wealthy individual who seemingly cannot live without domestic help, but cannot bear to pay fairly for it. Of course, the issue at hand is about more than class and finances – to permit domestic workers time off, and to compensate them fairly, is to empower migrants and upset the power dynamic that the kafala system enforces, in part, to control the ‘demographic threat’ and obscure dependency on foreign labour.