My father is not a statistic

The son of a migrant worker writes about the fragility of migration and how the pandemic has affected his family

Standing under an Acacia tree in front of his taxi in Abu Dhabi, my father was on a video call with my mother, trying his best to convince her that everything would be okay. But my mother was not. She looked tense. She has been the finest coordinator of our family for the past 25 years; this was the first time she has not received any remittance. In March 2020, when COVID-19 hit the world, the UAE government announced a nationwide lockdown, and my father had to quarantine in his dormitory. Overnight he became unemployed. Not knowing if we were ever going to see my father again, if he would win this fight against this invisible enemy, was the beginning of the economic and psychological toll of the pandemic on our family.

Flashback to 2003. Dozens of villagers had gathered in front of our house one evening to welcome my father. It was a very common scenario in my village during those days, every time somebody returned from abroad, a large crowd gathered to greet him. It was like a festival, though I still do not understand why everyone was so happy. Maybe they knew they would receive a gift – chocolates, body soap and sometimes even a torchlight.

"...he was a voice through the landline phone and messages in audio cassettes; the words in his letters."

I grew up in a lower-middle-class family of migrant workers. At the age of 22, my father was one of the first in our extended family to migrate to the Gulf. Since then, overseas migration has become part of our DNA. Around 90% of my relatives are migrant workers, most of them in Gulf countries. I grew up listening to their struggles, economic successes, and sometimes their ruined career. There were tales of how middlemen cheated, obtained fake medical fitness certificates, how 'free visa' turned my uncle into an alien in the desert. I saw many of my neighbours go abroad with a visit visa, knowing that soon they would lose everything and be detained. But they were ready to play the gamble. I saw my aunt crying when her husband was thrown into jail in Saudi Arabia. Then there was my cousin, who never had the chance to see his father's last breath. And there goes my father who left us for Saudi Arabia when I was four months old and returned to Bangladesh when I was five years old. That was probably his third trip to Saudi Arabia.

I still remember that day when I first met my father. Until then, he was a voice through the landline phone and messages in audio cassettes; the words in his letters. I felt shy when he hugged me. To be honest, I did not feel any emotional connection with my father. The dozens of toys he brought me made me happier than seeing him for the first time.

Growing up without his direct supervision was hard, especially for my mother. But that was the sacrifice we had to make. Because my extended family of nine depended on my father's income. During his migration cycle, he hardly could save any money for the future or an emergency like the pandemic.

Fast forward to 2019, I was at the airport with my father, an overseas migrant worker for more than 32 years, leaving his family one more time for Abu Dhabi. We did not exchange many words, but tears. I promised my father this would be his last trip. Since I started a new part-time job, I assured my father now we could both pay off our debt. This would take two years; after that, he would not have to work anymore, I told him. My father waved goodbye. I saw a tired man leaving, without any dreams left for himself, a man who sacrificed his golden age for his family, who always found happiness among us.

But COVID-19 changed everything. This pandemic showed us how vulnerable the migrant workers and us, their families, were. There is a general idea in our society that migrants are very well off, and as the family of a migrant worker we also faced this social pressure to appear so. The pandemic made it worse. Nobody saw the silent tears of my mother, nobody will ever understand why my father couldn’t save money for an emergency like this, though he earned a lot. Nobody will know why a university topper like me had to pause my study.

I have never seen my father this hapless. He was in lockdown for months, sometimes passing his days on an empty stomach. The food provided by the company was hard to eat. Because he has diabetes and other chronic diseases, I used to send medicine from Bangladesh. But with the closure of air travel, I no longer could. My father was forced to buy medicine locally, at a high cost. Soon his savings were gone. In the dormitory there was little space for exercise, his health started to deteriorate. Every time the phone rang I was prepared for the worst news. I know very well at this age my father cannot bear the pain of Coronavirus.

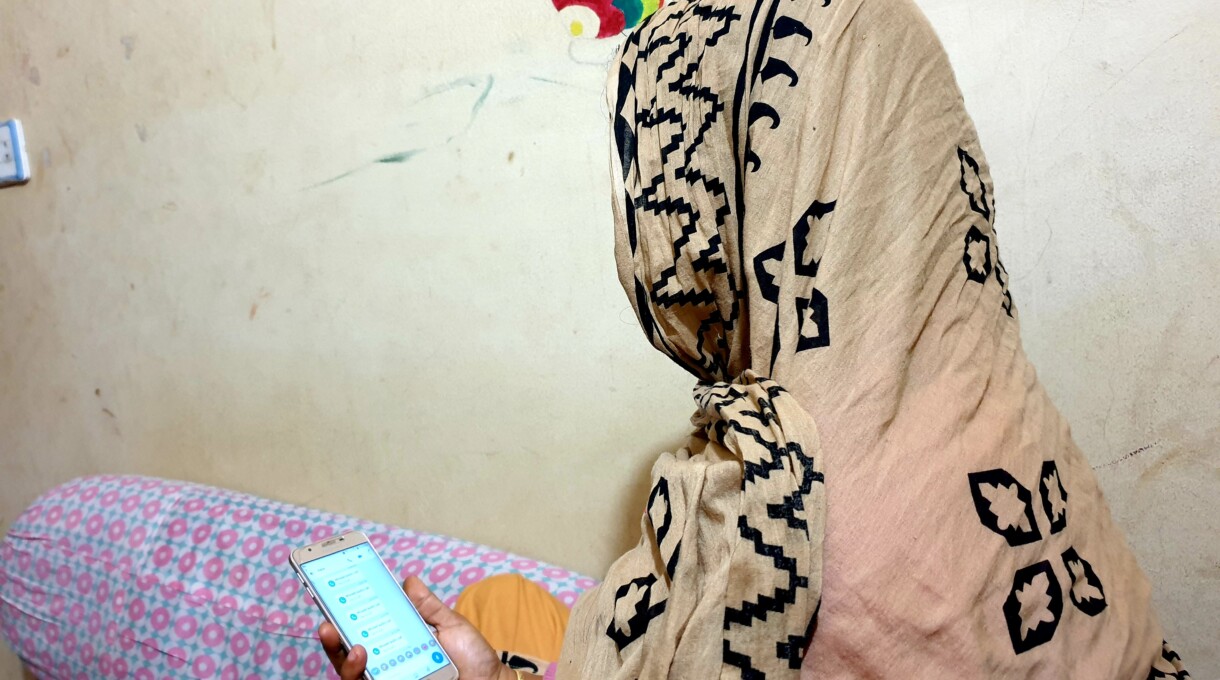

Above: For the first time in 25 years, the family received no remittance. Mosharaf's mother then started gardening on their rooftop to meet their food needs; Top: Waiting for a call from her husband.

One day, my father sent pictures of his food. I could not stop my tears. As soon as the UAE government partially lifted the lockdown, my father hopelessly started roaming around Abu Dhabi with his taxi hoping that he could earn some money. But there were few passengers. Since the lockdown has eased, my father spends around sixteen hours a day in the driving seat. If he cannot earn more than AED6,000 in a month for the company, he gets nothing. For ten months now my family has received no money from him. As a result, I had to pause my postgraduate study and start a full-time job.

In the middle of all this chaos, the company started terminating people. The first victims were those who had low revenues and health complications. My father met both criteria. Every day I heard that some of his colleagues were called by HR. “Why are they doing this to us? There were no people on the streets. People are avoiding public transportation. We are taking all the risk but if there is no passenger, how is it our fault,” my father asked. I had no answer.

This is not just about my father and our family. During the pandemic, almost all of my migrant relatives lost their income. I still remember a text from my cousin, who is working in Qatar: "How can I pay the debt? I hope I can bring an end to this pain. I cannot handle the pressure anymore." I received a similar text on Facebook from another migrant worker, who could not return to Saudi Arabia due to suspended flights. In my village, local shops were hit hard due to the low flow of remittances. Many of the shops are owned by returnee migrant workers and their main customers are migrant families. A number of my relatives could not fly back to their countries of employment because their visa had expired. They all are facing an uncertain future. After losing their jobs overseas, they are now struggling to survive in Bangladesh.

"I have realised my absent father may not be able to tell me how to live. But he lived a life and showed me what life is."

My work at Ovibashi Karmi Unnayan Program (OKUP), a community-based migrants' organization in Bangladesh, has given me the opportunity to meet hundreds of migrant workers across Bangladesh. I have seen the same emptiness and loneliness in their eyes that I see in my father's.

These migrant workers sacrifice everything for their family. Their remittance becomes the cornerstone of the economy. And we keep expecting more from them without providing them with any real support. I have documented 500+ cases of returnee migrant workers whose rights were violated. I witnessed how these returnees have gone through hell during their migration cycle. They work in extremely dire conditions that are not suitable for human beings, become the victim of wage theft, and get duped at the hands of their employers, recruiting agents, middlemen.

This is accepted as normal. Project after project implemented, paper after paper published, seminar after seminar organised, but the situation remains the same. To the stakeholders, next time before designing a programme for migrant workers, my humble request is to talk to them – not just through FGD, KII, Survey, but a real heart-to-heart conversation.

I am not an expert on this issue, but it seems migrant workers like my father will be only measured by the amount of money they remit. I wish it were not so. I wish the stakeholders would do a better job of protecting the rights and dignity of millions of migrant workers across the world. I can say these migrants do not want much, they just want to work in a dignified environment where their rights will be respected.

Despite all the negativity, COVID-19 brought my father very close to my heart. I have realised my absent father may not be able to tell me how to live. But he lived a life and showed me what life is. These days when somebody asks what my greatest fear is, I say, "I hope my father does not turn into a statistic."