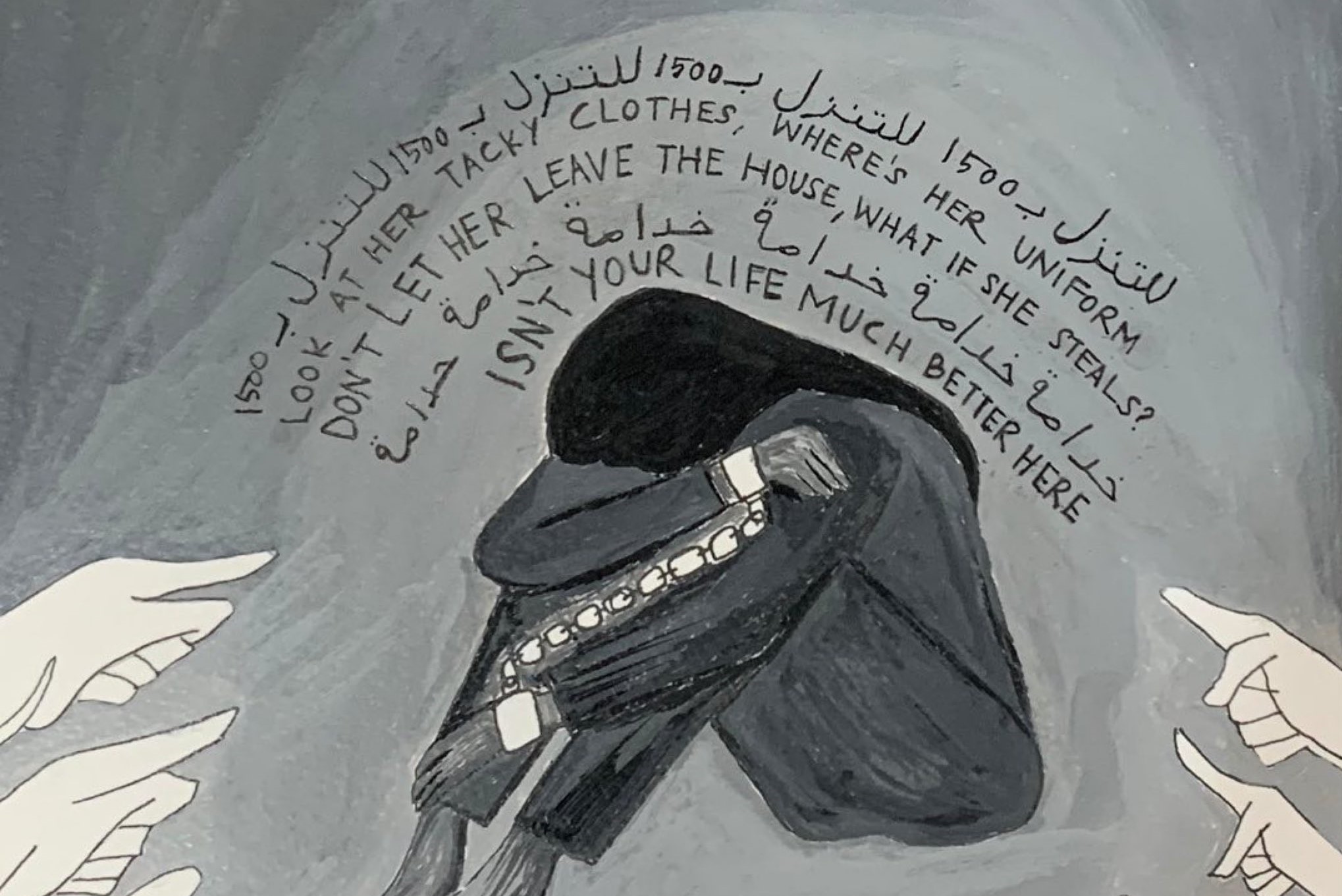

Correct terminology doesn't erase systemic injustices

Saudi Arabia banning the use of 'servant' does little to improve the lot of domestic workers

Saudi Arabia’s labour reforms came into force last month, easing restrictions on some workers’ ability to change jobs and leave the country. While it remains too early to evaluate their impact, the main criticism of the reforms so far has been the exclusion of millions who are not covered by the labour law, most of whom are domestic workers. Moreover, the reforms still maintain barriers, both financial and procedural, to changing jobs and exiting the country. Nonetheless, the government's exaggerated claims have largely been amplified by some international organisations.

In what appears to be an extension of this PR exercise is the recent directive that bans recruitment agencies and employers from using the word “sale” (bey'), “for purchase” (sharaa’), and “concession” (tanazul) when referring to the recruitment or transfer of domestic workers services. The order also bans the word “servant,” khadam and stipulates the use of “domestic worker” (a’mala al manzelia) instead. Recent updates to laws that pertain to domestic workers no longer use the term “servants” either.

According to Okaz, the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Development (MHRSD) issued a similar circular warning recruitment agencies and employers to avoid using advertisements with words or phrases that “violates the dignity of migrant workers, domestic workers and those of similar status.” Publishing personal documents such as identity cards or photographs of workers in such advertisements is now also prohibited.

The circular also stressed that workers should not bear any financial costs for transferring sponsorship and that the consent of the worker is required for transfer.

Local and regional media outlets have adapted their own glossaries accordingly and rushed to heap praise for the directives, without noting the lack of legal protection for domestic workers — as if changing language has suddenly and materially improved working conditions.

Many citizens took to Twitter to point out this issue. One viral tweet read: “I say we focus on important matters such as working hours, vacations, and their rights as a marginalized class, and inshallah, you can call her princess of cleaning for what matters.”

انا اقول نركز في المهم مثل ساعات العمل والاجازات وحقوقهم كفئة مستعبدة، وان شاءالله تسمونها اميرة التنظيف مايهم https://t.co/ZYeSyHFdas

— العنود البقمي (@3nd_m) March 31, 2021

Another account tweeted:

https://twitter.com/kroos_8t/status/1376779744461590529

“Treatment is more important than names. The important thing is to monitor the people that domestic workers work for, otherwise what is the point of naming her a worker while treating her as a slave.”

New terminology cannot extend dignity when the laws that govern domestic workers actually strip them of it. The ban may result in a change in tone in referring to domestic workers in official and quasi-official channels. But for it to percolate to private households and change behaviour will require stronger laws and enforcement; allowing workers to mobilise; and an overhaul of the very nature of the sector, which is now almost exclusively live-in, and on-call, 24x7.

The lack of meaningful legal protections, compounded by the sponsorship system and weak redressal mechanisms, subjects domestic workers to exploitative situations that they cannot easily leave. According to a recent Amnesty International report, several domestic workers in Saudi who were victims of wage theft, harsh working conditions, and physical abuse were unable to transfer jobs or seek redress. Instead, they were taken into custody and transferred to the detention centre.

A Ugandan domestic worker who is currently in Riyadh told Migrant-rights.org that she was forced to work even after her contract ended, and did not receive her due wages. She says her priority is to go back home — not how she is named.

“I have worked with my sponsor for two years when my contract finished they refused to let me go home, they made me stay and work for six months more and didn’t pay all my wages…I went to the police to complain and they took me to this centre.

“I am stuck here for two months now and the employer is not giving back my passport, I just want to go home.”

Unlike regular workers, domestic workers in Saudi still need permission from their sponsors to leave the country. Amnesty International interviewed at least five domestic workers that were detained because they fled abusive employers and had not obtained an exit permit from the sponsor to leave the country.

As is often the case across the region, domestic workers, who are among the least protected and most vulnerable workers, are usually left out of reforms because their work is devalued and invisible. Recent initiatives in Saudi such as the labour reforms, Wage Protection System and the new complaint mechanism on Musaned all exclude domestic workers.

The term servant is indeed derogatory. And it is derogatory because the term does not recognise the labour, agency and dignity of the individual. But changing terminology is only a gimmick if the legal and socio-cultural environment continues to disrespect and disempower workers. Inclusion into labour laws, better redress mechanisms that recognise the unique vulnerabilities of domestic workers (particularly women), reforming the recruitment methods, and holding abusive employers accountable are the pressing needs. Saudi Arabia must address these gaps to ensure its reforms are meaningful.

Photo credit: Ensaniyat Project; https://www.instagram.com/p/CIsSqBOhNlH/