Reports from Nepal reveal an increasing misuse of the project or short-term visas to bypass Qatar Visa Centre (QVC) procedures. Several civil society activists have raised concern over workers being duped with false contracts. The Nepali government does not approve short-term or project visas or contracts, nor does it make it mandatory that workers only process contracts through the QVC, leaving open regulatory gaps that can lead to severe exploitation.

According to HR procurement officers in Qatar, Qatari law does allow for project visas that do not require the due diligence compulsory for regular employment contracts under the Ministry of Administrative Development, Labour and Social Affairs (ADLSA). One officer, who prefers to remain unnamed, said that these visas were in fact allocated directly by the Ministry of Interior, and did not need the approval of ADLSA. “They bypass QVC procedures, and on arrival in Qatar will have to go through medical and fingerprinting alone. These visas are almost all issued for the completion of urgent World Cup projects. But there are others who misuse it, even for regular contracts.”

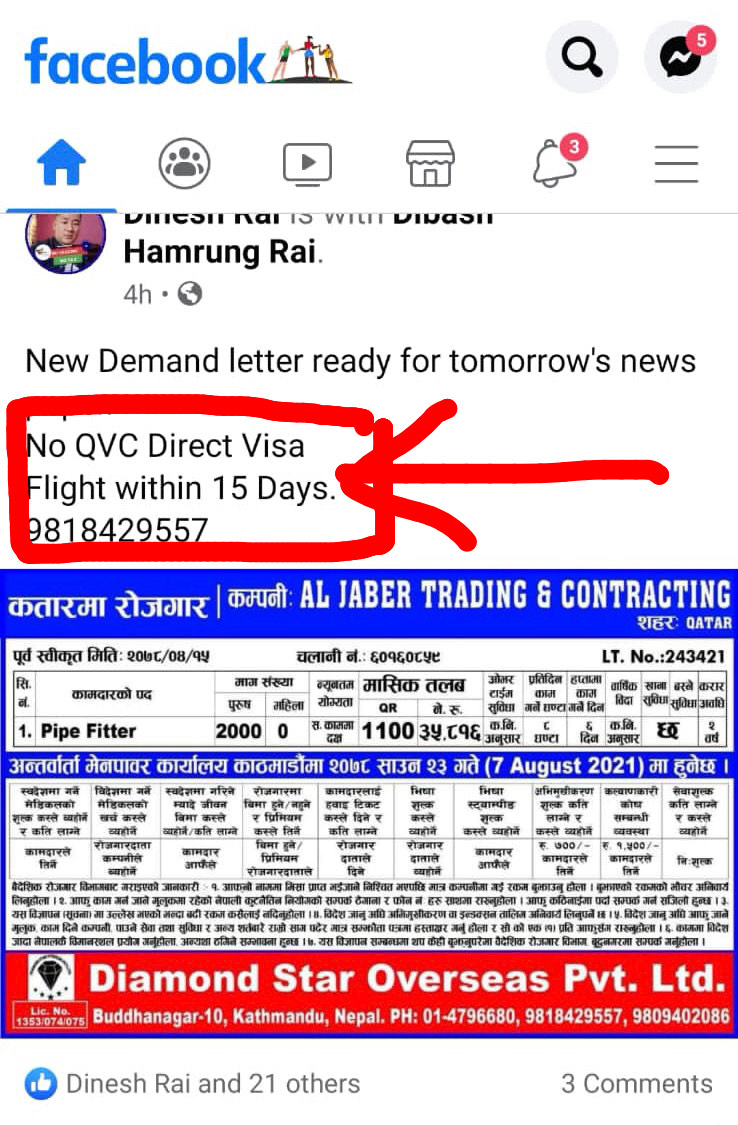

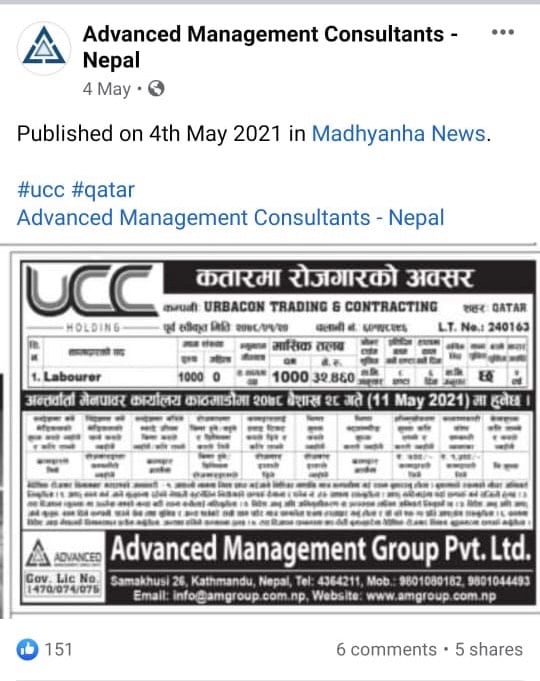

Migrant worker rights specialist Andy Hall has recorded evidence of this practice for several months now. All of the cases he has monitored involve recruitment by major Qatari contracting companies working on FIFA World Cup 2022 projects like Urbacon Trading & Contracting Company (UCC), Al Jaber, and Galfar Al Misnad (working on Al Bayt Stadium).

Hall points out that the advertisements for the recruitment of 65 labourers in Qatar (photo above) do not comply with the Supreme Committee for Delivery and Legacy’s (SC) ethical recruitment standards, as contained in chapter six of its Worker Welfare Standards.

Al Jaber Engineering, one other contractor of SC, has also allegedly failed to comply with the World Cup organiser’s recruitment standards. Workers are allegedly paying between NPR175,000 and 225,000 (USD 1500-1900) to obtain these jobs and visas, says Hall.

It is not yet clear who pays for quarantine on arrival in Qatar, but in order to comply with SC standards, this cost should also be covered by their employers, he stresses.

According to advocates in Nepal, the last 18 months of the pandemic have devastated the economy because of the drop in remittances, with new recruitment coming to a standstill and workers in the Gulf losing jobs. The desperate situation has led to even more corruption in the recruitment sector, with demand well short of supply. (We previously reported on the problems surrounding vaccine passports).

Qatar Visa Centres are supposed to streamline the recruitment process, though its role is restricted to the last mile of the process, i.e., the signing of the employment contract, medical and fingerprinting, the costs of which are paid by the employer at the destination. The QVCs are not involved in the actual recruitment process itself. However, they can potentially prevent contract substitution, a rampant problem, where workers sign a contract with better terms at home and sign another on arrival. QVCs ensure that the visa signed at origin is the one submitted at destination. Yet, the misuse of short term or project visas poses a new challenge to the system’s already limited scope of authority.