Religious and caste affiliations don’t give space for fight for labour rights in the GCC

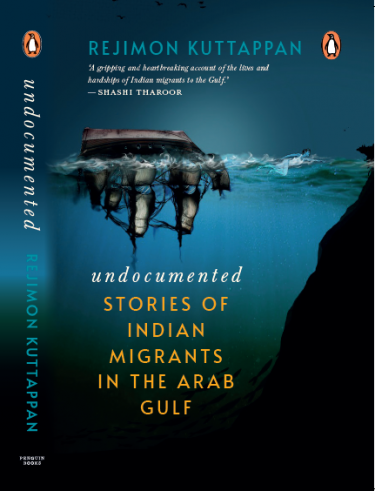

A Q&A with the author of Undocumented: Stories of Indian Migrants in the Arab Gulf

Despite decades of migration by millions of Indians, there is so little storytelling of those lives and experiences. Undocumented: Stories of Indian Migrants in the Arab Gulf by Rejimon Kuttappan is a critical contribution to fill this huge vacuum. The earliest of stories are from the 1960s, when people travelled without passports, undertaking weeks-long journeys in the hope of finding their riches in ‘Dufai’.

The author not only bears witness to these lives beyond statistics but also in illustrating how diverse the migration journey can be. Even in the path to becoming irregular or undocumented, even if the journey begins on similar lines, between the parenthesis is the uniqueness of each story. Kuttappan captures this with great empathy, immersing himself in the cases he helped narrate and helped resolve, and through it all is his own personal journey from an aspiring migrant to his deportation from Oman for pushing the limits of both journalism and activism in a country that gives no space for either. The stories illustrate the intersection of identity politics, patriarchy, media freedom and discrimination.

For Kuttappan, these are not just cases he helped with or stories told. These are relationships that he nurtures, continuing to be in touch long after the ‘problem’ has been resolved. There is humour and despair that lingers long after – Jumaila who had to be sponsored by her 11-year-old Omani son, whom she calls her ‘arbab’ or Appunni who returns to Kerala after great strife, to an unwelcoming family, calling his tiny car both his home and his coffin.

The book also veers away from painting people or communities as black and white. Instead, it draws attention to the systems and powers that enable abuse. You read as much about the empathetic Omani police or immigration officers who go beyond the call of duty to help migrants as you do about the Omani sponsors who were ruthless. Just as you read about the Indian or Pakistani migrants who risk their livelihoods to help those in distress as you do about the affluent self-serving. ‘entrepreneurs / social workers.’

MR speaks to Kuttappan about his own personal journey in writing the book.

The stories you narrate have a resolution. Either they return ‘home’ as they wish (even if it is to unhappiness) or stay back for a bigger commitment. What about the stories of those whose dreams were more fractured, unfulfilled?

Between 2010 and 2017, I have reported more than 3,000 migrant stories for different newspapers, agencies, and online platforms. But I also know that I have missed telling thousands and thousands of stories. How can I tell all the stories? Coming to the book, I wanted to tell a few real-life stories. So, I picked a few cases from the ones I handled. Yes, I agree that some stories go untold.

In 2015, I met an aged person, a Keralite, in Oman. He was sleeping on the verandah of a shop as it was a Friday, the public holiday. He looked weary. When I introduced myself, he greeted me and started to talk. He was sick and stranded. He was undocumented and was in his mid-60s.

He needed hospitalisation and a return to India. With the help of my friends, I managed to get him admitted to the hospital despite him being an undocumented person and approached the Indian embassy seeking help. The embassy made a plan.

We contacted the government authorities in Kerala. And they processed the papers required to establish him as an Indian citizen.. We finalised the repatriation date and bought a flight ticket too. But on the day of return, he passed away. He was an undocumented Indian migrant for some 25 years in Oman.

We then cremated the body in Oman. Even after nearing a happy ending, the failure happened. I failed to tell his story and find a happy ending too. Many more like this.

The book is also a commentary on the state of a free press in the region, but you had an editor and a chairman who was more accommodating. How much convincing did it take from your side?

We all were on the same page. We had a good understanding of storytelling. The Chairman and Editor were there for me anytime while I was on the field. Many times, when I faced trouble in Arab Spring protest tents and labour camps, they sent me help. Those experiences were quite convincing for me.

You speak of those who help migrants in distress like Binil (not real name). What is at stake for them as they continue to live there?

They have to be more cautious. Already, all are on the radar of the government. Anytime, they can be summoned, grilled, arrested, and deported. But they are ready to risk their job and earnings in the country as they see helping stranded migrants as more vital. Additionally, Binil always used to tell me that "helping a stranded migrant isn't a crime..."

There is a serious lack of civil society activism, except for charity, that makes access to justice and empowerment difficult. Where do you place your work within that?

Veteran CSO activists in Oman used to warn me on "breaching the activism limits.” I lost my job for "breaching my limits." But I have no regrets. I know that I did a better job than many other veterans there in the brief period I got.

As a journalist and an activist, did you worry about crossing/blurring the lines? Is it possible to pretend objectivity while reporting on human rights issues?

It was hard. But the editors helped to maintain the objectivity.

What do you want your readers to take away at the end of the book? Is there a message you had in mind while writing it?

Yes, the takeaway is All Is Not Well for labour migrants in the Arab Gulf. Readers will find that questions surrounding labour migration, modern-day slavery, and human trafficking are unanswered even now when the leaders claim to be champions of human and workers' rights.

India is the largest sending country of migrants to the Gulf, yet we have amongst the poorest protection at destination and on return. To what do you attribute this?

I have felt that the Indian government's understanding of external labour migration is poor. They are more bureaucratic than human-centric. So, the Indian government fails.

Why don’t migrants wield better political clout?

India's total population is around 1.2 billion. And the number of Non-Resident Indians is 13 million, which is only one percent of the total population. This one percent, even if they come together, will not get a say. They are negligible in a big country like India.

Additionally, the Indians fall into different religious and caste groups. These religious and caste groups fall into political parties that have different aims and objectives. Migrant welfare never finds space in their priority list. Now, let us take the case of an Indian labour migrant in the Arab Gulf. He will be failing to see him as a struggling migrant. He will never ask for migrant rights. But will be pushing for religious, caste, political rights as dictated by their bosses.

Doing this work, reporting on these issues, what kind of an impact has it had on you?

Both positive and negative. Positive is that such stories and this book are bringing respect for me and my family.

The negative is, by being open, I am risking my safety. Many Arab Gulf countries have banned me. Additionally, after losing my job in 2017 for exposing human trafficking through a news story, I am struggling financially without a regular income. I am the sole breadwinner of my family. Income loss is depressing.