“If my husband touches you I will kill you”

Rape, abuse, neglect, and death threats: the lives of Kenyan women returning from Saudi

TW: This article contains sensitive and graphic descriptions of abuse,

rape and sexual assault.

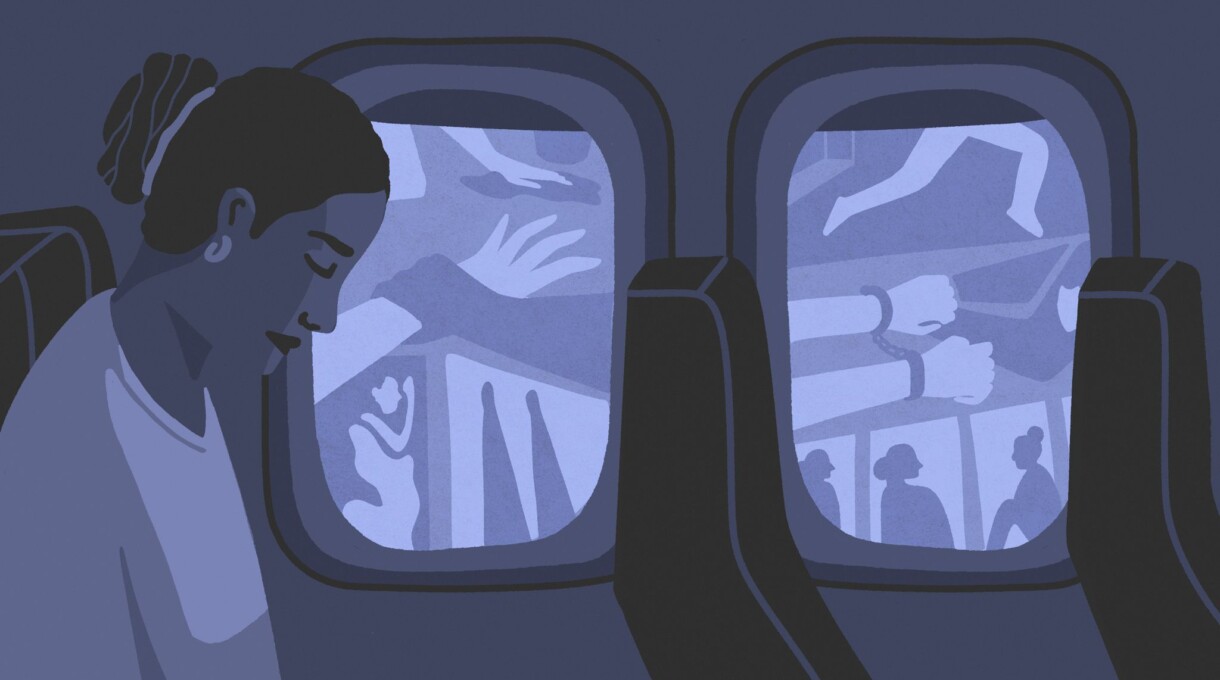

The stories merge, one woman’s trauma echoed in another’s nightmare. One survivor’s smile waning bearing witness to another’s unhealed wounds. The nods of acknowledgement, the sighs of empathy. They’ve all been there, but they know each one’s hurt stings differently. Some eyes are bright with unshed tears, some are empty, some laughs are of gallows humour, a few of shared wins. Some scars are physical and on display, but the ones that fester most are invisible.

Through in-depth interviews and focus groups with Migrant-Rights.Org, Kenyan women share stories about their life in the Gulf and the wider Middle East. While they all speak of long work hours, poor or no pay, lack of nourishment, and verbal abuse, almost all who have been to Saudi Arabia share tales far more tragic. Rape, sexual assault, torture…every anecdote shared has physical or emotional evidence. The burns, the limps, the breathless gasps, the estranged families.

In a dank, badly lit room in Nairobi, 12 women come together. Four wish to go abroad, and the rest jaded with experience are eager to share. The advice flies around the room thick and fast, accompanied by mirthless laughs.

“Patience.”

For what? another asks.

“For accommodating all the insults.”

“Be ready for sleepless nights.”

“There won’t be enough food.”

“Get used to a lot of black tea. A lot. And kubooz.”

“Panadol is your doctor. You have only that, however sick you are, even if you feel like you are dying.”

This draws loud laughs from everyone.

“Expect not to have sanitary towels.”

“Your own soap.”

“Or oil.”

“Or even drinking water.”

Ruth, who spent two years in Hafar Al Batin and Dammam, Saudi, is brusque with her inputs. “Expect that when your contract ends you won’t be let go easily. (Continue reading: Sisterhood of Survivors)

The trauma continues as they arrive home. Many who return without meeting their goal come back to empty homes or hostile environments. A perceived shame for being a victim of abuse.

Like Celestine, who chooses to live away from her young kids. “I am homeless, I live with my friend Feith. I am scared to be with my kids. I am scared the demons in my head will take over and I will kill myself and my kids.”

Her friend Feith sits by her, reaching out with her good hand. The other hand is healing from severe burns inflicted on her by her employer. Feith somehow appears stronger. She escaped and helped Celeste out too.

You will be raped. You will be beaten. No action will be taken. You will have a child as evidence of rape. Still no action. The police, the embassy, the office all collaborate to make you work only. You have no rights.

(Report continues below, after Abuse Beyond Comprehension)

Abuse Beyond Comprehension

Sister Florence is a professional counsellor with Counter Human Trafficking Trust-East Africa (CHTEA). While the organisation has helped many returnees from Lebanon with a seed fund to start a business, Sr Florence has worked with dozens of victims of abuse who have returned from the Gulf states, including those that Migrant-Rights.Org helped repatriate.

The highly traumatised are taken to a safe house on arrival. “I meet them twice a day, as they need constant support. At least at the beginning. When they are in a good-ish place, we reduce the sessions.”

However, their families don’t always accept them.

“We have victims of trafficking from other countries in the world, but none as bad as the ones coming from the Gulf. Especially Saudi,” she says and wonders if it’s because of a clash of culture or misunderstanding. While victims from Europe are usually those trafficked to brothels or into prostitution, in the case of the Gulf, it’s women who go to work in households, she explains.

“Some things are beyond comprehension. Father and sons raping the worker, women standing by and not doing anything…Rape is taboo, but a rape like this is even worse. It is sex slavery. They become objects. They are beaten and burned. They are penetrated with bottles and vegetables. They are also forced into abortions. And if the pregnancy continues they are jailed.”

The taboo is so deep-rooted, that women don’t even use the word ‘rape’. “They will describe everything else. Say bad things happened to them, but the stigma attached to the word is so bad, that they won’t say they were raped. Healing is such a slow and tedious process. Some are suicidal and need to be observed all the time. Once they leave the safe house they still have to be monitored. All of this is resource-intensive, expensive.”

Sr Florence says the trauma women face begins when their documents are confiscated, and then their phones. It weakens them. “It is chipping away at their personality, their humanity. Still, people go, because there are some success stories.”

It’s not just women who are subject to sexual assault and rape. “I have also spoken to some men. They’ve been sodomised. Abused. But they keep quiet. They are working as watchmen or in construction. They don’t talk about it. They suffer in silence. Then they end up with problems of substance abuse, alcohol, drugs, being suicidal, unable to cope with what they’ve endured.”

She is critical of the whole anti-trafficking agenda for leaving men out. “There are safe houses only for women and children? What about the men? Even if trafficked they are seen as victims of labour abuse alone.”

Sexual predators

Despite what she went through, it’s Feith who provides succour to Celestine,28, whom Feith feels had it worse. As if torture needs to be graded.

The two women went to Saudi at the same time with the same agent. Celestine ended up in Hafar Al Batin in the east of the kingdom, not far from the Kuwait and Iraq borders. Things were not so bad for Celestine to begin with. “They gave me food. I worked 8 to 8. They treated me well.”

After two weeks, the husband started coming on to her, barging into her room, and knocking on the door when she would go for a shower. She informed the agent in Kenya, who did nothing. She could not tell the wife, who had told Celestine at the very beginning that if baba touched her, she (the wife) would hurt her.

“The man started coming to my room with a gun. On 3 February (2020), the lady was not home. He came and raped me. And he continued raping me over the coming months until November. In the fifth month, he raped and hit me with the gun on the head and I fainted.”

She was taken to the hospital but warned not to complain to anyone. She was sent back home with medicine and the sexual assault continued. “He would also hit me. There are marks all over here [patting her stomach, chest, genitals]. He would stomp my genital area with his boots. Then he started anal rape too. I would scream and cry in pain.”

They would never miss a prayer but would come back from the prayers and mistreat you.

She finally called Feith, who advised her to run away since the agent was of no help.

One evening as Celestine was deliberating her escape, the employer brought home six men and they threatened to rape her, kill her and dispose of her in trash bags. “I just ran. I found my way to the office. They called the police, but the police asked me to go get evidence from the same family. The agent said the same. I refused. They beat me and sold me to the brother of the employer.”

Celestine’s tone is flat and her voice soft as she recounts the months of horror, but silent tears fall steadily through the one-hour conversation. Feith asks her in Swahili if she would like to stop. She pauses for a sip of water and insists on continuing.

At the new house there were 30 people, she says. By then, all her injuries were infected, with pus oozing out, and no medication — none of which was considered evidence. Here again, she worked from 6 am to 3 am, with hardly any food and no pay.

“On 29 November, the son came to my room to rape again and started beating me. Now the bleeding was heavy (points to her genital area). They then served some food with something green in it and said it was medicine for Covid. A child in the house came and told me don’t eat that. A 10-year-old boy. He said it was poison.”

[Feith interjects. “Children save lives. So often they come and help.”]

“It’s just like a brothel, if you want to sleep with anyone this was your centre.”

Celestine developed terrible stomach pain and bleeding, as she had eaten some morsels. She was taken to the hospital. Finally, she was sent to the agency office, where she was locked up with other Africans with similar cases. “We all ran away to the police somehow. And they helped repatriate us in February 2021.”

The poison has affected her liver. The abortions she was forced to have, and other injuries from the beatings she received, have also impacted her health and made it impossible for Celestine to work. She receives some help through church groups but says she is still haunted by what happened.

“Therapy is taking time to heal. When I shower and see my scars, everything unravels again. It’s too difficult. I feel so dehumanised. My mind is not working,” she says.

“I survived to speak for the silent ones.”

All the returnees have some version of the sexual harassment they faced.

Sophia, who did a short stint in Saudi before escaping abuse and overwork, spent another three years in Qatar. “It was slightly better… I worked in different households. But everywhere you face sexual harassment. In the household, when you go out with the driver. Babas asking for massages. You have to be smart and resourceful to escape all this, but you don’t always succeed.”

“And the men in the house, every chance they get, they show their ‘pee pee.’ Absolutely no peace of mind. Can’t even sleep,” says Peris, who worked in Dubai.

Atieno, 26, went to work in Tabuk in 2018 but had to escape after three months. “Though the household was small, the man kept trying to sleep with me, was sexually harassing me. When I told the wife she got so angry she beat me and didn’t give me food. How is it my fault?”

Afraid the situation would continue to escalate, she managed to go to the police and contact the Kenyan embassy with the help of her friends.

“I had friends who helped and guided me. But many don’t have that support. They even kill themselves in desperation. In that house, the husband was molesting me. I screamed and he beat me. He did bad things. When I wanted to file a police complaint I was told it was expensive, so I did not. I already have a child I am struggling to take care of, and when that man did things to me I was scared of pregnancy. And even more scared of being killed. I am still dealing with what I went through.”

At the detention centre, you are raped… if you become pregnant they try to send you back quickly. If you have a child there you are stuck.

“You sleep with dead bodies; the detention centre is a brothel”

Vinne, a single mother who now works with other victims of abuse, listens to the group of women she brought together to share their stories (see Sisterhood of Survivors). She chips in with her views every now and then but watches closely as others grapple to say what they wish. Her voice is low, belying only briefly the feistiness within. Once the group disperses, she takes a seat to share her story.

“I grew up in Kibera, the largest slum in Nairobi. I was 24 and an agency offered me a job in 2014. I didn’t have to pay a single cent. I was supposed to go to Dubai via Mombasa and was told I will be paid KES35000 (US$295). I ended up in Saudi. The thing is, your business with agents ends the minute you depart the country.”

After three days at the Jeddah airport, her boss picked her up. “It was a big house, and the work hours were long. The language was a challenge. There was another Kenyan working there too.”

The work she could manage, but the overtures from the men of the household was a different challenge.

“The man and his sons were sexually harassing me all the time. I complained to the madam but she wouldn’t believe me. I was threatened at gunpoint by the men. One day they were all out, and the eldest son attempted to rape me. We fought. I hit him with a heavy object I found near me. When madam returned the son complained and said he wanted me out of the house. But they kept me and the harassment continued daily.”

Four months later Vinne decided to escape. She took the opportunity to throw the garbage out to run away, along with the household’s other worker, Martha. Martha was caught. Vinne kept running until she ran into a man who offered to help her, and took her to a detention centre in the Al Rehab district of Jeddah.

“There, I regretted running away. Because that is where you saw people dying every day. You just see that, and there’s nothing you can do. You even sleep with dead bodies next to you. And there’s not enough food. No one cares.”

“These security guys want to have sex with you. In Saudi, it is so hard for men to interact with women because it is against their culture also, so this is the opportunity they get to sexually harass you and you are helpless and you can’t do anything. I became so sick. I was in the centre for two months and got pregnant due to sexual harassment.”

She says the embassy never came to her aid in the centre. When her family complained in Kenya, they said they couldn’t trace her. “I can’t forget that centre. People were dying. Fighting for food. Being raped. And no one to help us.”

Vinne recalls men coming to the shelter/centre and raping the inmates. “It’s just like a brothel, if you want to sleep with anyone this was your centre.”

She believes she was deported quickly because she got pregnant.

“When I returned to Kenya I was in the hospital in Kenyatta for four months, then was connected to the organisation Kudeha who helped me. They gave me support. Connected me to other organisations. My son is 6 years old now. In school. He does not even have an origin. I don’t know who his father was.”

Panadol is the fix. You can be dying, and they will give you panadol. However ill you are, you are not worth more than a strip of panadol.

Burdened with work and panadol as a panacea

Feith (31) went to Saudi just before the pandemic hit, in December 2019, the same time as her friend Celestine. She landed in Dammam and was taken to Arar, a city in the northern part of the Kingdom near the Iraq border.

She had to undergo a 14-day pre-departure training course and obtain a good conduct certificate in order to migrate. “The minute you land everything you were trained for vanishes. You are ‘dumb’ the first day.” It doesn’t help that the workers are given little to no time to acclimate to their new environment and are expected to hit the ground running as soon as they arrive. And the good conduct certificate means nought, as the employer’s conduct remains unchecked.

“The work hours were so long, and you had to survive on leftover food. My contract said I would be working for a family of four, but I lost count of the number I saw there. There were five families. My boss, his family, his mother, brother, mother-in-law… Another worker came the next year. We both still worked 17-18 hours. And we had to cook for their catering business,” recounts Feith.

While she was paid monthly, everything else about the job was taxing on her physically and mentally. With the first salary, she bought a phone and hid it. “When they first checked they saw I had two phones, they expect you to have two. So I made sure I had another.” That foresight would stand her in good stead when things went south.

“Every time we fell sick we were given Panadol. Once I was so ill I could not stand. There was severe pain here,” she says indicating the right hip which to date poses a problem. She tried contacting the agent in Kenya to no avail. Finally, on the fourth day of excruciating pain, she was taken to the hospital. “I told the doctor about my pain, they wanted me to do a scan the next day, before treating, and told my boss too. But they took me home and got me a strip of Panadol. I wanted to rest, but they made me cook for the catering business they ran.”

The following day Feith had to go to the hospital again for a blood and urine test, and once again, she was not allowed to wait to get the scan done. She had to go back home to cook for the catering clients.

“If you complain you get beaten.” Feith had posted on Facebook three days earlier about being ill. There were suggestions that she should run away as a last resort. The next day after preparing the morning meals, she made a dash. “I took my phone and put it inside my panty, took my blanket, and ran from the house. It was 12 noon. I walked in the heat, all the signs were in Arabic. One old man who saw me asked ‘binti (daughter), where are you going?’ He gave me water and called the police who came immediately. I had only my contract, but no passport or ID.”

The police called her employer and instructed them to bring her passport and iqama, took copies, and asked them to take her to the hospital or to the agency office. When they took her back home, Feith assumed it was to take her things and put her on a bus to the office in Hafar Al Batin, which was 12 hours from Arar by bus.

“But Baba demanded my phones and beat me up so severely. He said, ‘no police, no office, no hospital, the doctor said you are ok.’ They forced me to go cook.”

While she was cooking, the employer started ranting at her again, looming over her from behind – ‘You are here to work not to be sick. In Saudi, there is no sickness. I buy you, you are my property.’ As Feith turned to speak to him, he picked up the kettle of hot water and poured it on her.

“I felt nothing, they burnt my right arm. I was numb. I was doing everything and yet I was being treated badly. I went to the bathroom and took out my secret phone, took a photo of my arm and sent it to my husband. He sent it to the agency, who sent it to the office in Saudi. And they sent the photo to my boss. I told the other Kenyan in the house if I die, tell people. She was new.”

The employer threatened her with a gun and made her record a video statement saying he did not hurt her and it was an accident. The wife warned her not to change her statement. She was later sent to the office, where she was given three options. Work and finish the contract, work for another house, or to pay for a flight and go home. Seeing no reprieve, Feith attempted to run again. She ran by a Red Crescent tent and received some help, but the police returned her to the office again, asking them to resolve her case. “I didn’t get any medical help for my hand. There were some Ugandan women there who tried helping me and said my hand will rot at this rate. That’s when I posted videos on social media, and good samaritans raised money to send me home.”

When Feith arrived in Kenya, it was to an empty home, only to discover the money she had remitted had been spent by her husband, who had taken another wife.

When you run away, take nothing with you. Even if you are going to the police, take nothing. Nothing at all. If not they will accuse you of stealing.

Policing the victims – the weak arm of the law

Like Feith, many of the other women also attempt to seek help from the police. Time and time again, they are sent back to abusive households. Peris,45, who decided to go abroad to make ends meet and put her kids through school after her husband lost his job. She connected with an agent, packed her bags and bid farewell to her family. “I had to do my paperwork and training so I borrowed money from well-wishers and went to Nairobi from Mombasa. I cleared the medical and soon after was put on a flight to Dubai.”

Peris was promised a salary of AED600 (US$165) and that she would work for a small family. She even had a call with her would-be employer. “She said she had two small kids and was pregnant so needed help. I was scared as you hear such bad stories. Speaking to her, I was reassured.”

As soon as she landed in Dubai, the employer took her passport. “You say goodbye to your passport then, you won’t see it again. You have to be prepared for that.”

The surprise didn’t end there. “When I went to the house it was a big family, a big house. I don’t think it was the house of the same lady I spoke to. You don’t work for one family… I was made to work in three houses, all relatives. Taking care of old people too. I worked late into the night.”

She snorts when asked about work hours. “No working hours. No off. You work until the work is done. And the work is never done. You wash utensils for hours and you can barely stand. They just give Panadol if you feel sick. And all you get are leftovers – you eat what remains after they’ve eaten.”

Peris slept on the floor in the same room as the old parents. “They would tap me to wake me up and I had to take the old lady to the toilet. I was on call even through the night. If you complain they say, ‘Africans don’t get tired, Africans are strong’.” [listen]

Unlike her compatriots, Peris didn’t know to hide a spare phone, so she was dependent on the employer to communicate with her family. “Once in two months, they allowed me to call. They would stand right next to me, insist I speak only in English and keep saying ‘Not in your language’.”

Stuck in the homes of her employers, and working in multiple households, she asked to return home after a few months. “They refused to let me return saying they had paid a lot of money to get me. I worked for 8-9 months. Finally one day I ran away. I had nothing on me. I wanted to go to the police. I didn’t even know the name of the family.”

The police checked her records and found out the details of her employer. After a week the family came, spoke in Arabic with the police, and took her back. The police asked her to finish the contract before returning.

“They kept shouting at me, but thank god they didn’t beat me. They said I can’t go anywhere. At the police station, I said I will not work three houses even if they kill me. They just said ‘yalla, yalla’ and sent me back home.”

Once she went back to the employer’s home, Peris stood her ground and refused to work in other homes.

At the police station, she was told if she ran away she would disappear because the family had paid a lot of money for her. “When I asked to be taken to my embassy, they said it wasn’t the rule of their country. When you actually gather courage and manage to run, they still return you to the family? So I fight in my own way. I screamed, rolled (on the floor), and refused to do work. These were my ways of coping.”

Peris continued to work for almost two years until she fell so ill the family sent her back home. “I know what I saw and went through. I don’t wish that for my worst enemy. Tea and bread are all I got to eat. I would just eat what I can while cleaning. I read of people being raped or killed and I thank god nothing like that happened to me. Still, I went through a lot, because you will do anything as a mother to help your children go to school.”

Francina, 37, went to Dammam in 2019. Her workday, like most other domestic workers, stretched from before dawn to after midnight, and it was a huge house with six members. “The treatment during the first three months was not so bad”, she says. “But they would refer to me as khadama and shagala (servant).”

The children she was taking care of started beating her up. “I complained to the mother, she just said kids are mentally ill, so adjust. They were 18, 16, 13 and 4 years old. I tried withstanding all this. There was support from other Kenyan domestic workers on WhatsApp groups.”

She worked for a year and nine months, and her health kept deteriorating. “I tried using the hotline, but the police just called the boss…they have no power over them.” As a last resort, she stopped working and insisted on being taken to the agency. She stayed for another two months there. “So many youngsters in the office there. Domestic workers who run away, with even worse stories. We were made to sleep on the floor. We had to pay for our own food. And all the while the agency made them go work in multiple homes.” Finally, with the help of a Kenyan NGO, she returned home.

Lydia, who worked in Sakaka, Saudi, says “If there is rape, you can’t complain. No one can share. No action is taken. If your boss impregnates you they try to send you back quickly. Once you have a child in the detention centre you are stuck. Can’t go back. No one is imprisoned for rape. Even when there is evidence of children. If you are beaten, no action against the abuser. When you are not paid, no action against the employer. End of the day, you have no rights. Be it at home, immigration, labour office, police station, office or embassy. They are all in collaboration to force people to work and not help them.”

“I was deported because I was pregnant.”

Dehumanised and a diet of black tea with kubooz

From the get-go, Eva’s Saudi experience was fraught with disrespect and disregard. “When my boss picked me up at the airport, the first thing he said was either remove my braid or cut my hair.” (She had braided her hair fresh just before she left Kenya.) She stayed in the store room and worked in a huge house where 12 people lived. “I had to steal food and eat hiding. They gave black tea and kubooz,” she says, with a distaste echoed by many of the other women who were on a diet of tea and bread. She was trapped inside the house and would sneak off to the verandah for her only glimpse of the world outside.

Eva had to work at the employer’s home, his mother’s place, and also the farmhouse they had in the village. After about seven months, she fell very ill and was taken to the hospital. “The nurse asked mamma if they gave me food and rest. They lied and said yes. The nurse said I won’t survive like this, but mamma threw the medicines they gave me in the dustbin.”

Unable to continue working, she pleaded with her boss and was allowed to return to Kenya. She paid for her own way back, and did not receive all the dues she’s owed for her work.

Lydia, 34, says while the agency in Arar gave her passport and contract, it was taken away when she reached the sponsor’s home. She lasted just a month there.

“I was allowed to sleep only for 2-3 hours in the morning. No rest at all. You are recruited to work in one house, then they send you to their parents’ and other relatives’ homes to work there too. I had to strike and refuse to work. They really do not respect you at all. The minute you sit down for a rare meal, usually tea and kubooz, they will call you. Make you work more.”

When she complained, the agency sent a driver to take her to the office where she stayed for two months. “They won’t send you back home. They will find another sponsor. My first sponsor found another sponsor and they got a refund. I was treated well in the second house though a very big family. Then madam got pregnant and things got worse. I had to work from 9 am to midnight.” After 11 months she wanted to leave but was ‘sold’ to a broker.

“A woman called Fauzia. When they didn’t send me back to the office, I alerted my family. Fauzia used me for piece work. One week here, two days there…I told her I don’t think this is legal and that she was a stranger. She realised I was intelligent. She sold me to another house. I worked there for 10 months. Five members, but they made me work in other houses.”

Having spent close to two years in Saudi, Lydia was looking for an out. Her health had deteriorated, and the employers were reluctant to take her to the hospital. Neither the agency nor the embassy responded to her call for help.

“I opted to run to the police. When you run, run with nothing, so you are not accused of theft. The police demanded I show my iqama. I only had a copy. The second sponsor’s ID and details were different. I had moved so many homes…they said my fingerprints were missing in the system. The police called the office. They took me to Sakaka. They couldn’t ascertain my ID.”

She stayed in the office for seven months, three without work. The office refused to release her to the embassy.

At the end of her tether, Lydia took to social media.

“I went to the labour office too. I was fed up. The office, Al Faisal for Recruitment, was treating all of us so badly. Beating us when we refuse to go work elsewhere. I exposed them on Facebook. There were 30 of us from different countries. Even those who finished their contract were being forced to continue.”

Meanwhile, she tried making sense of the bureaucracy.

“They kept telling me my papers were in the labour office but when I went there it wasn’t there. One day I went and met a captain who was sympathetic. They helped me get my ticket and leave. I had my documents on my phone. I wasn’t a runaway. I knew my rights. Not everyone does. But after I exposed the office other women got help too. There was so much mental torture, but I was willing to fight. I expected the embassy to come to my aid, but they did not. The Saudi office was angry I was posting online. The Kenya office is still mad at me.”

She knew her activism came at a cost. “If you are outspoken, you become a danger to these people. I was punished for being outspoken. Others in the office were allowed to leave, but mine was delayed. Before that, I was in the Sakaka detention centre for one month before going to the office. You are at the mercy of the police and the labour officials.”

You can die working or you can die trying to escape. Choose the latter.

Sisterhood of Survivors

In a dank, badly-lit room in Nairobi, 12 women come together. Four wish to go abroad, and the rest jaded with experience are eager to share. The advice flies around the room thick and fast, accompanied by mirthless laughs.

“Patience.”

For what, another asks.

“For accommodating all the insults.”

“Be ready for sleepless nights.”

“There won’t be enough food.”

“Get used to a lot of black tea. A lot. And their bread.”

“Panadol is your doctor. You have only that, however sick you are, even if you feel like you are dying.”

This draws loud laughs from everyone.

“Expect not to have sanitary towels.”

“Your own soap.”

“Or oil.”

“Or even drinking water.”

Ruth, who spent two years in Hafar Al Batin and Dammam, Saudi, is brusque with her inputs. “Expect that when your contract ends you won’t be let go easily.”

Vinne, who brought the women together, speaks softly. “I would advise you to have a positive mind. As much as my experience was bad, I have interacted with other ladies whose experiences were good. There are stories that motivated them. Some girls, their employers have visited them in Kenya. Not all are bad like ours,” she pauses to gather her thoughts. “At least 20% are successful, 80% not so.”

“What is successful?” a couple of the women ask. “Accomplishing what you expected to,” she says, reluctant to say more. But Vinne does have a lot to share, and she does so once the rest of the women have left the room (see main text), after having taken many selfies and making many promises to come together and fight for their rights.

A few of the women in the group, especially those who returned from Lebanon, felt they were on track to accomplish their goals, but the recession and pandemic blindsided them, and they were forced to return without meeting them.

“Everyone tries their luck, you can’t tell someone not to go,” says Lucy who spent many years in Lebanon.

But Ruth is vehemently opposed to people going to Saudi unless they have relatives there to help them. “I dread Saudi with every bone in my body. Go elsewhere. Don’t go there. You may never be back. There are those who are lucky but the majority come silent. I survived to speak for the silent ones,” she chokes, unable to continue.

She has a unique way of expressing herself, a rhythmic repetition of the phrases, speaking from the periphery at the start of the discussion, filling other people’s gaps, mocking the questions posed as if to say, ‘isn’t the answer obvious’ or ‘isn’t the answer irrelevant now’.

As the first hour progresses to the second, her emotions reach a crescendo. From staged indifference to reluctant sharing to angry tears interjecting her powerful words.

“I worked for 20 hours a day. I had to beg them for sanitary towels.”

“I think they tricked me […] I will never sign anything in Arabic.”

Ruth did not go unprepared. She read the contract, understood the terms, and asked the right questions of her agent. “But when I went there, I was paid far less and was treated so badly. I was sent to my kafeel’s aunt’s house too. All for KES20000 (U$170), when I was promised SR1000 (US$270). That was so unfair. I could do nothing. I didn’t know their language. Going there is very easy, coming out is so difficult.”

She stares long and hard at the four young women hoping to go abroad and says, “Be patient. Be quiet. Don’t be open to them. Keep your thoughts close to you. Be smart. Don’t share details. Hide your phone, connect with your sisters on Facebook, and connect with other runaways. Let them [the employer] be speaking freely so you know them better than they know you. Learn their language, but let them not know that, you can then know when they are plotting against you.”

She relives her days in the household, unblinking, glaring at the girls as if daring them to go despite her warning. “You can imagine being locked in the house for nearly six months. You just see the road outside from the window. Not going out at all. You call the embassy they don’t help. You call the agency and they say we are collecting a group of girls, you run away. How can you run away in a country that beheads people? I want to come home. I’d never advise anyone to go to Saudi. I wouldn’t want anyone to suffer the way I did.

“Imagine being locked up for six months.”

“Saudi is sending more dead bodies than other Arab countries. In six months, 40 bodies. Why are they coming with their mouths closed?”

Vinne tries to steer the conversation to a more positive note, but her experience is in contradiction. “Advising someone not to go is not fair as we can’t provide for them here. We can only help them by connecting them to groups. I had the worst experience. But I got support, I can speak without crying. It took me years to get here. When I suffered, the Kenyan embassy said I was not on their register. I was illegal. There was no reference to my agency. But I was there, I was Kenyan, that wasn’t enough for them,” says Vinne.

“How can they say they don’t know where you are,” asks Ruth. “They take your eyes (iris scan), they know your kafeel, everything is in the system, how can they not find you? They are grappling (sic) with us. I tend to believe the government officials are involved.”

Celeste, who returned from Riyadh last November, says “I tried adjusting. Where can I go? They had my passport and iqama. You know, there’s this thing called kubooz. I hate it with a passion.”

Peals of laughter drown her voice. They’ve all been there. Kubooz and tea for days on end, for every meal.

“Madam and her son would go out and eat and bring me kubooz. I ate it with water because the fridge is closed. One day I said, enough is enough. When she said to take the ‘baala’ (garbage) out, I said this is my only chance. So when I went out, I didn’t come back. I was there for six months and found my chance. I had nothing on me. Even the slippers I wore in a hurry were one blue and the other red.”

“I hate kubooz with a passion.”

A taxi driver saw her on the road and took her to a lady who promised to help, who then took her to another house. “That madam was very nice. She paid me well and was good to me. I worked there, but then madam was scared she would be caught because I had no documents. So I went to the embassy. They said I had to pay SR6000 (US$1600) to go home. Where will I get that money?”

She went to the police and told them she had no documents and that they could do what they wanted, which she hoped was to send her back home. “But they said go find work, we won’t catch you. Then I worked in one policeman’s mother’s home for one month for a pittance. Then I went to another police [station] and said I want to go home. He asked me if I was pregnant, and why I wanted to go back?”

Celeste insisted on returning home, so she was sent to a deportation centre, and then back to Kenya.

“What we realise is that the person who picks you from the road will pay you well, not the one who took you from Kenya, you know why? Because they didn’t buy you and spend money,” she tells the room.

Others chime in. Live-in work, tied to one household, living in their home was a recipe for disaster, they all agree. They each have a name for part-time work – ‘piecemeal’, ‘rental’, ‘freelance’ – which is less exploitative, they feel.

“One month at a time is best. When it’s a 2-year contract you are stuck and the office abandons you. Sometimes you work so far away that you are dumped in the desert. Can’t even run for help. Ignorance is killing us. The employer’s ignorance. The worker’s ignorance,” Ruth states.

“The lady police she can’t touch us […] because we are black […] we hid our gadgets.”

The conversation veers towards coping mechanisms.

The majority say throwing the garbage out gives them an opportunity to see where they live, who is nearby and to be prepared when they have to escape.

Vinne says a guy who helped her said she should pretend she was crazy. “To act crazy. To cry loudly, a refrain in Swahili ‘take me back to Kenya’ — I was ready for anything.”

“I even slapped my boss one time. She poured hot water on me. So I had to slap her. With swollen eyes and crying, she took me to the police. I told them, look at my stomach, there is [a] burn, what can I do to her? I refused to go back to her house,” Celeste says.

Though Ruth had signed a document in Arabic, which she didn’t understand, before leaving Kenya, once in Saudi she refused to do so. “When I was in the police station the ‘shurta’ (after she ran away from the employer) were forcing me to sign a paper in Arabic and I refused. He said he would beat me. I said do anything you want, I won’t sign. Maybe I am signing my own death sentence, who knows!”

They then brought someone to explain to her that the letter said she was being taken to a detention centre since she refused to work, and that she would be sent home from there.

“I asked them what have I done to be taken to detention. Have I stolen? I finished my contract.” She did end up at the detention centre with dozens of other Kenyan workers.

“Even there, we organised a demonstration as there were many Kenyans. Not shouting or doing anything, but we were not eating their food. We hid the fruit and the milk and would hide at night and eat, but the rice and the big lamb we didn’t touch. Then the big police asked us why we were refusing to eat. We told them we want to go back to Kenya.”

Since she had hidden her phone on her person, at night she was able to speak to human rights organisations in Kenya and post on social media about their plight.

The lady police refused to touch the African workers, when they were supposed to be searched, which gave the women an opportunity to hide their phones.

“The police officers said you are not supposed to have phones, how did you manage? We told them, the lady is lazy. She was searching us like this, this — (acting out gingerly touching her arms and legs with one fingertip). She saved our lives with her racism. I asked the police again what have I done, what have I stolen? I finished my 2-year contract and I want to go home. Why am I in detention? The next day I was on a flight; I paid for my ticket and went home.”

Ruth had been saving her salary, hiding the money inside her bra. The employer didn’t always take them to the exchange to send money home. “I wanted to go and send money home as that was the only way to know the surroundings. If I run away where can I go, the route I can take? But when I was not taken out, I hid the money.”

“They say African don’t get tried. African strong.”

While Ruth advises the newbies to hide their money, Lucy warns against it. “You know it’s also not safe to keep money on you, they say you stole the money. I would not advise that. It’s risky.”

Which then leads to another round of tragi-comic sharing of what happens when they send money home.

“You send money here, people are eating it.”

“My mother ate my money.”

“My husband ate my money. And found another woman.”

“Sometimes I don’t want to take my kids’ calls because they want money all the time.”

“When you step on a plane you are automatically rich according to your family. People would rather die there than be cheated here by our loved ones.”

“Even if they stab me, they are at least paying me there. But once you go abroad with your family the relationship is always about money.”

Families grapple with uncertainty

Zubeida sits by a dilapidated building near an old railway station in Mirtini, a suburb of Mombasa. She is frantic as her daughter Mona, 24, is stuck in Dubai and her employer is refusing to let her return.

Mona went to Dubai two years ago and was promised a salary of KES300,000. She hasn’t been paid in five months. Though the employer’s family is not big, there is a constant stream of visitors. Her visa was renewed without her consent, and now the employer is demanding compensation to let her go.

“She ran away to the police, but they returned her to the boss. Boss said he had paid for her visa, so not letting her go. She went back to the police after 4-5 months. They are so angry with her that she went to the police. So now they don’t give her salary, and sometimes no food even.”

Stuck between a rock and a hard place, the family is asking her to wait and not run again, fearing she may disappear or land in more trouble.

“I want my child to come back,” pleads Zubeida.

There’s a similar plea from Abbas Omar, wanting his wife back home.

In early May, at the Mombasa office of Haki Africa, an NGO, Omar has been waiting for hours, since 8 am. He has been holding vigil here for several days, hoping the agent who sent his wife Fatima, 38, to Saudi will come to speak to him. Fatima had gone to Jeddah in January this year. She worked for two months but could not continue. Playing her WhatsApp voice notes, Omar says she was being overworked and verbally abused. “The house has three floors and she has to do all the work. And she worked till 3 am and had to be up at 6 am again. And they shout at her all the time. They give her food but keep saying she eats but does no work. It’s mental torture.”

She was returned to the agent after two months, but she is not able to come back to Kenya. “Yousuf (the agent) committed to send her and help her if she is in trouble. Now he does not answer my calls.”

This brings Omar to the NGO Haki Africa, which has been active in advocating for detained and stranded Kenyans and helping with their return. A case officer there says the agent claims the delay in return is due to Ramadan.

Omar plays his wife’s voice notes on repeat. “Now in the agency they give food only once a day and nothing at all the first few days. Just water. Listen, she is crying in these messages that she will die.” He is willing to raise money for her ticket but is lost as to why there has been such a delay.

The case officer says that the embassy staff at the destination do not cooperate. “Unfortunately, they see us as the enemy. Kenyans are kept in detention for long. Embassy not proactive at all. In most cases victims claim neglect. Sometimes they spend even a year in detention centres. With other nationalities, resolution seems quick. On average, it takes 4-5 months to return a Kenyan worker.”

“There’s no passport confiscation in Saudi” – Agent

Later in the afternoon, Yousuf the agent makes an appearance. “I didn’t answer his call because he didn’t know how to talk,” he snaps, refusing to make eye contact with Omar.

“They (workers and their family) don’t understand it’s not easy to just leave there and come back. There are so many processes. A lot of money has been invested. We pay for everything: training, birth certificate, passports.”

He insists things have changed for real in Saudi. “There’s no passport confiscation now. Musaned has changed everything. It keeps track of all parties. Workers and employers and agents are all registered in the system before they leave home. Should be there in other Gulf countries too because we have problems there.” He adds that Qatar and UAE give ‘too much freedom’ to women and the Kenyan workers misuse it.

He is unrelenting in blaming the workers for refusing to adjust. “Before they go we tell them it is not a holiday. They are going there to work. Just do that and come back. They want to leave for small things.”

Pointing to Omar he says, “I tried convincing her to work. How can we spend so much and they just come back? For small issues. We asked her to change jobs, but she has pressure from her husband who doesn’t want to take care of kids.”

The two men exchange angry looks as the case officer steps in to resolve the issue and talk about Fatima’s return.

Yousuf is not done. “It is such a long process to be trafficked…I mean to migrate, how can they just return? Women think they are going for a ride there and want to come back immediately. We need punitive methods for them.”

Footnote: The report was made possible with the help of several organisations in Kenya which work closely with migrant workers in distress. Their contact details are available on our resources page: https://www.migrant-rights.org/resources/

Laws in principle vs in practice and all the pitfalls in between

At 2.15 million square kilometres, Saudi is the largest country in western Asia and the 13th largest in the world. Close to 40% of its 34 million population are migrants. Of the 11.5 million migrant domestic workers worldwide, of whom 27.4 % are in the Arab states. Saudi accounts for the single largest population of migrant domestic workers at 3.7 million.

Yet, this group is excluded from the Kingdom’s labour law protections and the few recent reforms.. The main regulations that apply to domestic workers are:

- Ministerial Decision No. 310 of 1434 on domestic work (known commonly as the domestic work regulations); and

- Ministerial Decision No. 605 of 1438 permitting domestic workers to transfer between employers in certain circumstances.

As per these regulations, the employer is obliged to provide proper food and medical care, and the employer is prohibited from employing a domestic worker outside the employer’s household. The worker is entitled to a paid day off, and a minimum of 9 hours of rest a day. Under the anti-trafficking law of 2009, the employer must not “threaten, defraud, deceive or abduct a worker” or take advantage of a worker’s vulnerability to coerce to consent for the purpose of sexual assault, forced labour, or servitude.

Passport confiscation, wage theft, and forcing a worker to do uncontracted jobs are all indicators of human trafficking, according to Mohammed Al Masri, the secretary general of the National Committee to Combat Human Trafficking, an affiliate of the Saudi Human Rights Commission. The penalties include up to 15 years in prison or a maximum fine of SAR1 million, or both. Yet, these practices are rampant and go unchecked, with little evidence that employers have been booked under the anti-trafficking law.

Workers’ testimonies indicate large-scale violations of these laws and insufficient mechanisms to address these issues.

Access to justice continues to be a major concern, as highlighted in our previous report. The Musaned system, introduced in 2014, was supposed to address some of the issues faced by migrant domestic workers. However, MR’s analysis found that “Musaned is a Saudi initiative concerned with the last legs of the recruitment relay – it does not, and practically cannot, reach as far back as the middlemen, brokers, and other stakeholders that migrant workers and employers encounter before they reach registered agencies in their own countries.”

Even though governments of countries of origin and recruitment agents have access to the system, it only enables access to records and does not directly enhance accountability. “The platform lacks a complaints mechanism for workers, relegating disputes to the existing – and weak – Ministry of Labour and Social Development’s (MLSD) resolution system. Making these records reliably actionable remains a difficult endeavour and one that workers cannot realistically pursue on their own.”

Technically, the system is supposed to make it easier to locate domestic workers, however, with workers being sold internally and put to work in multiple households outside of the main sponsor’s home, traceability also remains an issue.

*Some names have been changed, and only first names have been used in other instances