Months before World Cup, workers forced to return home early and with pending dues

Workers involved in both public protests and smaller ones that flew under the radar were deported without due process

Earlier this year, Qatar instructed all construction companies to reduce the number of migrant workers in the country and “prepare a strategic plan for workers’ leave” ahead of the World Cup tournament. In a circular issued by Ashghal, Qatar’s Public Works Authority, companies were asked to complete all construction and maintenance works by the third week of September.

A Migrant-Rights.org investigation uncovered a number of violations against Nepali migrant workers who were sent home by their companies. According to documents obtained by MR and testimonies from returnee workers, major construction companies repatriated workers before their contracts ended. The workers say they were removed from their jobs with no proper notice and communication, and without receiving their full dues. Some were told they were on ‘long leave,’ and therefore did not receive their end-of-service benefits, but it is unclear if they really can return to Qatar to work once the football tournament ends.

According to data from Nepal’s Department of Foreign Employment, the number of Nepali workers returning home has increased in recent months. Nearly 80,000 Nepali workers returned from Qatar between January and July of this year. About 10,700 workers came home in July – a 4% increase from January. The highest returns occurred in April, with over 13,000 workers, a 27% increase from January, coming back to Nepal. Conversely, the number of Nepalis departing to Qatar dropped by 39% in the same period.

Mohan and colleagues who participated in the Al Bandary Engineering and Electrowatt protests asked Qatari officials if they could work for other companies. They were told that they could not, and would be jailed and fined QR5000 if they attempted to do so.

Strangling protests, denying dues

Al Bandary Engineering and Electrowatt

Workers who raise their voices against wage theft and exploitation often face detention and deportation, as in the recent case involving Al Bandary Engineering and Electrowatt employees. About 200 workers from the two companies, which are both subsidiaries of the Bandary International Group, protested on the streets of Doha on 14 August 2022. Over 60 were detained and deported, while 140 remain in the country awaiting their dues. Not all who were deported received their full settlement. The company stopped paying salaries and wages in February 2022, and later terminated work in June.

Mohan was terminated in the middle of his contract with no explanation. Electrowatt laid him off three months before returning home, during which he received no pay, and had still not paid Mohan’s full wages by the time he left in August.

“The company people ran away. The office was closed,” he said. “Qatari police gave me the flight ticket then only I could return home.”

Throughout his employment, he was never paid on time. Before he was laid off, Mohan participated in protests against Electrowatt, but the company and government officials failed to address workers’ demands.

During the protests, Mohan and his colleagues asked Qatari officials if they could work for other companies. They were told that they could not, and would be jailed and fined QR5000 if they attempted to do so — despite recent legislative reforms in Qatar that, on paper, allow workers to change jobs at any point during the contract without permission from the current employer.

The 24-year-old wanted to work for the entire two-year contract period, but instead was among the first lot of 300 Electrowatt workers to be sent back home.

He had paid a recruitment fee of NPR180,000 (US$1400) to go to Qatar, taking a loan from a local moneylender with an annual interest of 36%. “I paid only NPR75,000 (US$590) but I still have to pay the rest,” said Mohan. “I don’t know when I will be able to pay it back. I may have to sell my house to repay the loan if I don’t find employment soon.”

In Qatar, Mohan earned QR1100 (US$300) working eight hours a day, six days a week, as an electrician assistant. He recounted his days in Qatar with grief. “I feel bad recalling the days in Qatar. Before going there, I expected to earn money and support my family financially. But I couldn’t even repay the loans. My expectations shattered within a year.”

While non-payment was the last straw for Mohan, he faced issues with his employer from the very beginning. His employer confiscated his passport when he arrived, and it took nearly two months to start work and six months to get his Qatar ID card.

Bal Bahadur, from the southern plains of Nepal, had a similar experience. He said that his employer, Al Bandary Engineering, forced him to return home without any compensation for his early termination. “I went to Qatar to work, to earn and to support my family. I even took out a loan to go there. But I was not allowed to work for the whole contract period. Who else will repay my loan?” said Bal Bahadur, who was his family’s sole breadwinner.

Bal Bahadur has no idea why he and hundreds of other workers were sent home. He heard that workers were asked to go home during the World Cup tournament, but he thinks there must be something more. “If everything is okay, why would the company people run away?” he asked. “We worked so hard for them for months, but the [company] officials ran away when we asked for the pending salaries.”

Bal Bahadur worked 11 hours a day, six days a week, and earned around QR1500 (US$410) a month. When he lost his job, he also lost the lifeline for his family of eight. “I can’t even afford food now. My grandma is ill, but I couldn’t pay for her medicine. I have small daughters to look after. I have loans to repay. Whom to tell all my stories of suffering?”

He is currently looking for work in another destination abroad, as he has no hope of being able to work in Qatar after the World Cup. “I know work abroad is not easy, but I couldn’t stay unemployed any longer. I must work,” he added.

Redco International

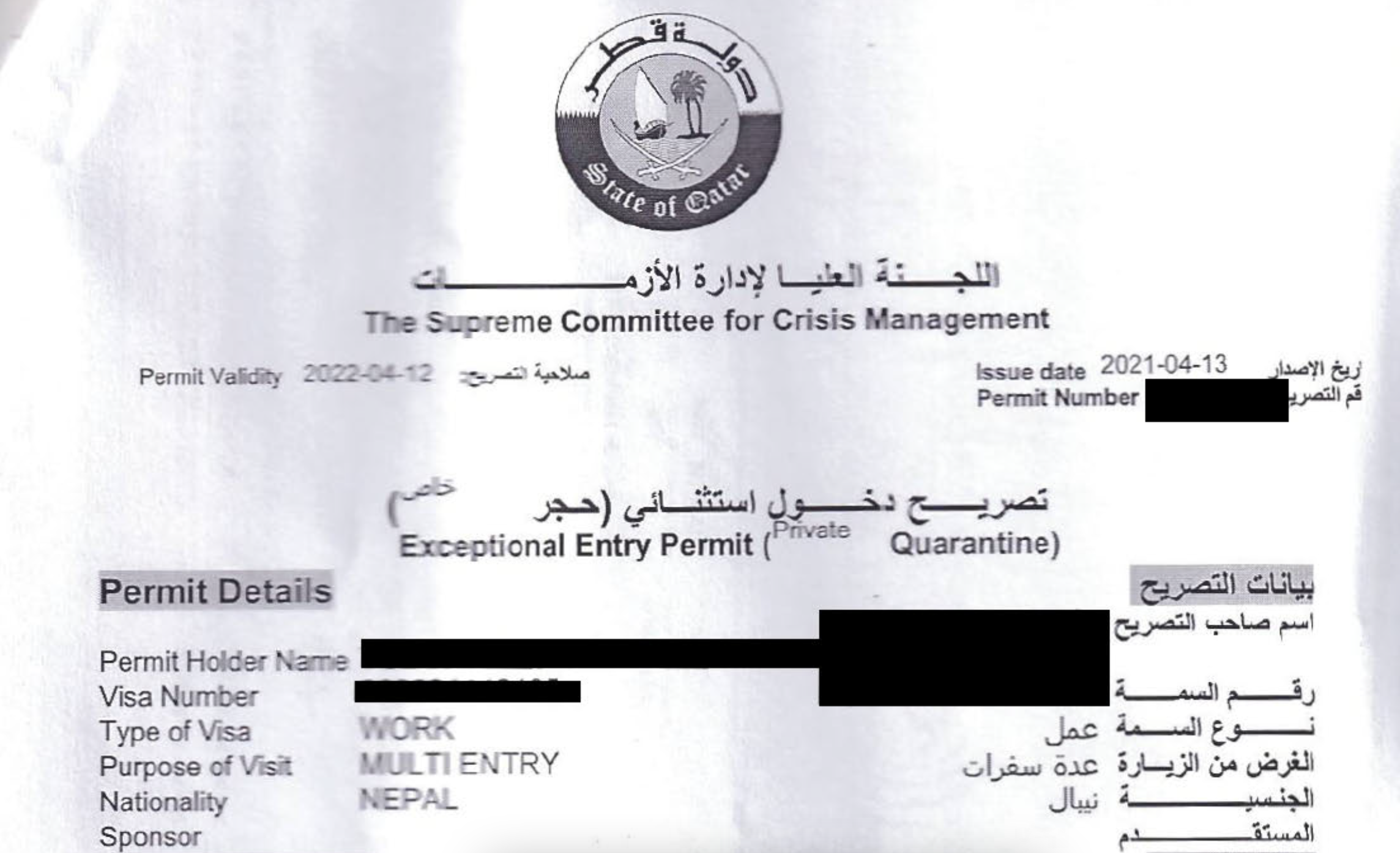

Ramji and Maniram both entered Qatar on an ‘Exceptional Entry Permit’ under the Supreme Committee for Crisis Management* to work for Redco International Trading and Contracting. Ramji was issued a two-year residence visa and Maniram a three-month visa, but the contract duration for both workers was two years. (*The committee was established in 2020, headed by the Prime Minister and Minister of Interior, ‘for managing crises and disasters.’ For more on misuse of short-term visas, read our previous reporting here and here.)

Eighteen-year-old Ramji signed a two-year contract with Redco International in November 2020, but he was sent home after only a year and a half. He told MR that Redco never explained why they sent him back before his contract ended. Instead, he heard from colleagues that the company was sending workers home in the run-up to the World Cup, and only realised he would also be returning when he saw his name on a list posted on the walls of the labour camp.

He is unsure whether he was terminated or is on ‘long leave’.

“I wanted to work more. Because I went there to earn money,” Ramji said, who had to spend all of his wages to repay his loan. “I could earn a little more money if I worked more. I don’t have any savings now. Nothing happened as expected.”

In Doha, he worked as a construction flagger at Stadium 974 in Ras Abu Aboud, controlling the vehicles that carry construction materials and debris for stadiums. He also worked outside Lusail stadium, where he erected detours, posted warning signs, and positioned the barricades and traffic cones at construction sites. Working eight hours a day, six days a week in the sweltering climate, he would earn QR1,000 ($275) a month. He used to work overtime two extra hours daily, hoping to make a few extra riyals.

Before going to Qatar, he was told by his Nepali recruitment agency Al-Samit Manpower that he could work for two years and “everything would be okay.” A first-time migrant worker, he believed the agents.

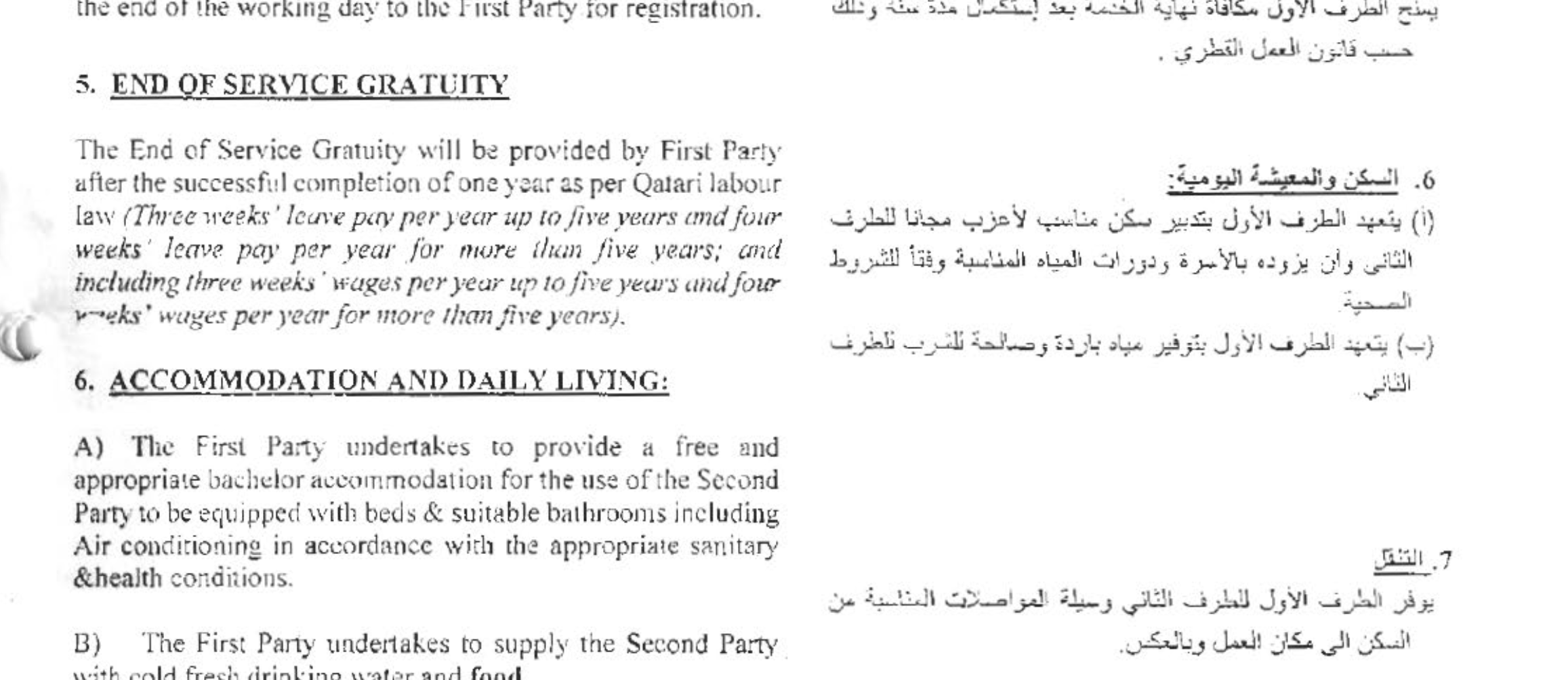

When Redco failed to pay salaries for two months, he and his colleagues went on strike, after which he received his monthly wages but none of the end-of-service benefits stipulated in his contract. “I heard that our company didn’t have the policy to give bonuses (gratuity) as other companies do,” he added. Both Ramji and Maniram’s contracts promised three weeks of paid leave as gratuity for every year completed.

His family of ten had relied on his income, paltry as it was. With no one at his home employed, he now works as a construction labourer in his hometown in midwest Nepal. All day, he fills gabion walls with rock and earns NPR800 (US$6.30).

Shyam, a current Redco employee, worries he could be sacked anytime. He has already seen hundreds of workers terminated and returned home. “Now the talk among the workers is about when we will see the list of terminated workers,” he said, in a phone interview from Qatar. “Many have already returned; we’re waiting our turn.”

He also alleges that Redco refused to give him a copy of his contract when he started the job – a violation of the labour agreement between Qatar and Nepal. “They didn’t even allow me to take a photograph of it. In Nepal, my recruitment agent told me I could work for two years, but Redco management said my contract is only for one year. They got me to sign it and kept the paper with them. I’m cheated by the manpower agent first and by the company here. But what can I do? I’m helpless.”

Redco workers reported the misuse of short-term visas, too. Last April, Al Samit Manpower sent Maniram to Qatar on a three-month multi-entry work visa. His recruitment agent told him he could work for two years. After a month in Doha, Redco International employed him and signed a two-year contract.

On September 22, 2021, Redco International requested final labour and immigration clearance from Nepal’s government to employ Maniram and 42 others, stating that the company would renew all government-related documents. Records show the government approved their employment a week later. (Job orders of companies or recruiters require approval from the origin country’s embassy or government.)

But Maniram was sacked only six months later. Before he was terminated, the company told him they could no longer employ him because he had a short-term visa. “Why would I go there if I knew I had to return this soon? I didn’t even know what kind of visa I had,” he said. “I wasted six for nothing. I couldn’t even pay my loan.”

Maniram borrowed about NPR200,000 (US$1570) from three local moneylenders to pay recruitment fees (NPR155,000) and other expenses to go to Qatar. He worked in Site 22 Industrial Area Bus Depot, where his main tasks involved climbing scaffolding and operating power tools, although his contract stated he would work as a painter and mason.

Before sending him home, Redco put his duty and others on hold for a few weeks. When the company delayed payments, the laid-off workers protested in their accommodations, demanding their pending salaries and the opportunity to find new jobs.

Instead, Redco posted a list (reviewed by MR) at the gate of the labour camp of workers who would be sacked and sent back home. The workers were told that many of the construction projects had already wrapped up, and they were no longer needed.

Maniram said that the company was downsizing, and that hundreds of workers from Nepal, Bangladesh, and India had already left the company even before he came.

When he left for Qatar, the 27-year-old had high hopes of earning decent money and supporting his family financially. He was hopeful he could make his family happy by sending back some money for household expenses. Instead, he finds himself in a debt trap. “I still have to pay back NPR60,000 (US$470). I wouldn’t be in debt if I didn’t go there or could get a chance to work for two years. But what can I do? My agent deceived me.”

As his high-interest loans pile up and expenses increase, he is trying to find another destination for foreign employment. “How can I raise my sons if I don’t work?” he said. “I wish my next employment wouldn’t be like this.”

He regrets that his time in Qatar has gone in vain. “I couldn’t even pay back the loan in that period, let alone earn some,” said Maniram. “I wouldn’t have gone there If my agent had told me everything correctly before.”

"The mudir of the company said to me at the Bin Omran office that they might ask me to come to Qatar again in November 2022. He also said, ‘If we don't invite you to work again, we will remit the rest of the money and you can withdraw from the IME office (remittance company) in Nepal’. When the mudir said this, the GM and PM of the company and the people from the Qatar government were also there.

"Gopal, employed by BOTC and worked on Al Bayt Stadium

Bin Omran Trading Company

Bin Omran Trading and Contracting (BOTC) is another company with a record of labour violations. Human Rights Watch (HRW) reported wage abuses by this “class A” company which was involved in several key projects in Qatar, including the construction of Al Bayt Stadium and the New Orbital Highway that links Doha downtown to several other stadiums.

Gopal, a general construction worker with BOTC, has worked in Qatar since the country won the bid to host the tournament in 2010, including on several World Cup-related projects like the Al Bayt stadium. The opening match between Qatar and Ecuador will take place on November 20 at Al Bayt.

For 12 years, he built scaffoldings in several stadiums, plastered countless walls of the new buildings, and paved asphalt on several highways, no matter how difficult the working conditions were in the blazing summers.

But nearly seven months before the tournament kick-off, BOTC sent him home, stating the company would be closed because there would be no construction work during the matches. Gopal, who worked tirelessly to make the World Cup possible, is not happy with that decision.

“How nice it would be for the workers like me to watch the games at the stadiums we ourselves made,” said Gopal, sitting on the hand-woven bamboo stool at his home in the hills in central Nepal. “But who cares about us? There’s no value for labourers in that country. I feel like the World Cup is an event of and for only rich people.”

Adding insult to injury, BOTC did not pay him all of his end-of-service benefits. According to Gopal and the documents he shared, BOTC remitted about NPR400,000 (US$3128). “But I still have to get about NPR900,000 (US$7038),” he added.

He doesn’t know who will pay his remaining dues or when he’ll receive them. But he is afraid the money is lost for good. “The mudir (boss) of the company said to me at the Bin Omran office that they might ask me to come to Qatar again in November 2022. He also said, ‘If we don’t invite you to work again, we will remit the rest of the money and you can withdraw from the IME office (money transfer service) in Nepal’. When the mudir said this, the GM (general manager) and PM (project manager) of the company, and the people from the Qatar government were also there.”

However, the 53-year-old had already signed a document attesting that he received all his dues, end-of-service gratuity, leave credit, and airline tickets. “I can’t read Arabic or English. I don’t know what they got me to sign in this paper,” said Gopal, showing MR the ‘acknowledgement of receipt of dues and discharge’ paper endorsed with his thumbprint.

Just a few months before he was sent home, BOTC had stopped paying Gopal’s salary for three months. He received his wages only when the workers went on strike. Given BOTC’s track record, Gopal doubts he will receive the remainder of his dues.

Another BOTC employee, Subash, shared his bitter struggle to get his dues. “We were not paid for three months. We protested against the company. We even went to the Labour Court. Then only we got the salary and settlements,” he said. “What is more frustrating than it when you don’t get the salary for the work you already did.”

Hassenesco Group

Hassenesco Group (HCC), which was responsible for several key projects in Qatar, has also sent hundreds of workers back to their home countries [see company response below].

Arjun returned to his home in southern Nepal this June, after four years in Qatar. His employer, HCC, said it was no longer in a position to retain workers and released a list of more than one hundred workers who would be sent back. Arjun was among them.

Unlike many other workers, he did receive his pending salary of QR9,500 ($2,610) and end-of-service benefits – money he now uses to pay the household expenses. The family’s sole breadwinner is currently searching for a job in another country. “I don’t think the HCC will invite me again. Even if it invites, how can I stay jobless for such a long period? So, I’ve already started finding an alternative. I can’t stay idle. My family’s responsibility is on my head,” said the father of three.

Arjun is aware that HCC – which describes itself as a “grade A” company that employs over 3,000 people – would be closed during the World Cup. “But the Qatar government could have found other jobs for workers like me. It would have been so helpful because foreign employment is our lifeline,” he added.

The 35-year-old worked on many construction projects in Qatar, including Al Baker Tower. A Christiano Ronaldo fan, he and his colleagues had planned to watch the World Cup final match at the stadium.“We were so excited to watch the game at the stadium. But the Qatari government sent us away from the country just before the tournament.”

Some 2,000 miles away from the Lusail stadium, where the final match will take place, Arjun now feels disgraced and humiliated. “Workers worked hard to build the roads, buildings, and stadiums, but they are being sent out of the country. It doesn’t look fair,” he said. “We are treated like trash. They don’t even want us to be visible among the international audience.”

Puskar, another HCC worker, said that the company did not pay all his dues before sending him home. “They didn’t give me gratuity, they didn’t pay for the overtime duty I did,” said Puskar. “I asked for my final settlements for months. But on the day I returned home, they said they cannot give.”

Previously, HCC had also stopped paying wages for several months, and even stopped providing food. He and his colleagues staged peaceful protests at the company’s headquarters. “They laid off the workers and closed the canteens for months. That time, we would beg for food and money from other workers,” recalled Puskar. “I borrowed 500 riyals from my brother. That’s how I survived.”

Three months ago, on the day of his flight to Nepal, the camp boss handed him an air ticket and 500 riyals and told him that the company was unable to pay all his dues. Puskar said he would have considered going to court, but had no opportunity to do so since they were only informed the company would not be settling their dues hours before the flight.

According to Nepal’s Foreign Employment Board, about 400,000 Nepalis worked in Qatar during the country’s massive construction spree in 2017-2018. Nearly 15% of migrants worked exclusively in the construction sector, as scaffolders, carpenters, masons, painters, steel fixtures, and similar jobs. About 8% of workers did electrical or mechanical work such as plumbing, welding, pipe fitting, air-conditioner fitting, and repairs.

*All names have been changed to protect identities as workers still hope for the Qatari government and employer to settle dues

MR has written to the aforementioned companies for their comments and will include their responses if and when received

Response from Hassnesco

“With Reference to the email dated on 31.08.2022, The Hassanesco Trading and Contracting Group of company is established in 1976 with the capacity of 12000 manpower strength. Hassenesco is doing ethical recruitments from various countries to fulfil the requirement of the company time to time.

Meanwhile, we did workers repatriation accordingly to the Qatar Labour law with settled of all the dues till the last date of work if the worker is eligible for it.

This is further to inform that expats with Qatar Residence permit are free to change the job any time to new company even without existing company authorization as per Qatar Labour Law.”