The Philippine’s 41-country ban (and subsequent deferral) made a splash last week, sparking discourse among different government agencies, migrants, and activist organizations. Though critics deemed the measures superficial, the sheer number of countries blacklisted have invigorated demands for more action from other nations. The Indonesian government subsequently responded to queries regarding recent changes to its own migration policies; Commentators speculate that the five month moratorium on labor export seems to have been lifted following informal agreements between the two nations. These negotiations include pledges from both governments, including Saudi Arabia’s promise to protect migrant rights. Indonesia’s policy towards Saudi appears to parallel the Philippines’, in that some of the most dangerous nations are deemed acceptable for employment with mere promises of migrant protections rather than significant, concrete evidence of actual improvement.

The purpose of the moratorium and related labor bans is to encourage governments to enforce fair migrant practices. But Indonesia appears to avoid dealing with migrant-related laws specifically, and instead attempts to belatedly correct problems that the absence of enshrined protections create. For example, in September and October the Indonesians government issued travel documents for 4,550 illegal workers who absconded from abusive employers. Migrant organizations recognized that repatriation was essential, but questioned what action was taken against the employers, and what measures will be implemented to prevent future abuse. These concerns can only be resolved by addressing the legal environment and ensuing sanctioned social practices in Saudi.

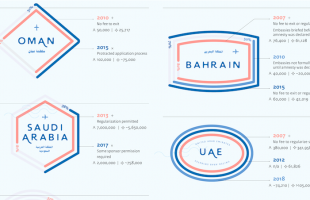

However, aside from Saudi Arabia, Indonesia’s migration policies may constitute a stronger stance against abusive nations than the Philippine’s proposal; Indonesia currently enforces labor bans on four nations (excluding Saudi Arabia). The government recently announced that Malaysia will be removed from the ban in december. But, the countries currently blacklisted appear more significant than those banned by the Philippines because they employ a larger number of citizens. The weighty contribution of Indonesians to the labor force and overall economy means the bans have a more tangible impact on these host countries, and may compel them to alter their policies. Nevertheless, the laxity with Saudi Arabia may impact the willingness of other nations to modify their laws - if the moratorium on Saudi Arabia is in fact lifted, other nations may wager on Indonesia giving into economic pressures before changing their own practices.

Critics emphasize that Indonesia needs to adopt tougher measures against labor-importing countries to ensure migrant protections are enforced rather than forgotten in “letters of intent,” - such as the pledge signed by Saudi Arabia just prior to the infamous June execution of an Indonesian maid. The Indonesian government recently formed several task forces to deal with issues facing its citizens in various countries, but the forces may have limited impact if they continue only to address the product of abuse while treading lightly around the nations that enable it.