Searching outside the Gulf for better models of labour migration

But, can 'temporary' migration schemes ever be pro-worker?

The Gulf countries depend heavily on migrant labour in virtually all segments of the economy. In Qatar, for example, 95% of the 2 million-strong workforce are foreign-born. This is true as much for highly-skilled, highly-paid occupations such as law, banking and medicine as it is for lower-paid jobs such as domestic work and manual labour.

The paradox is that while this dependency on a foreign-born workforce is anything but a short-term one, the GCC countries treat migration as an overwhelmingly temporary phenomenon. Although many migrant workers will do multiple stints in GCC over the course of their working lives, migrant workers’ visas are designed with a relatively short duration in mind and are generally tied to a specific job or employer. It is almost unheard of for a migrant worker to attain citizenship.

The model of temporary labour migration is on the rise globally as countries, especially those with lower fertility rates, look to migrant workers to supply cheap labour with few strings attached in sectors such as agriculture, fishing, and domestic work. So to a certain extent, the GCC countries have been practising what is now an international trend.

Perception of Temporariness

But there are two things that set the GCC countries apart from a labour migration standpoint. One, the sheer number of workers who come under this scheme, and two, the fact that virtually all workers, regardless of their occupation or skill set, are given similar treatment from a visa standpoint – that is to say, their permission to work and reside in the country contingent on a specific job or employer, with limited pathways to citizenship and an unspoken assumption that they will return to their country of origin once they have outlived their economic utility.

Elsewhere in the world, many countries make a differentiation between higher-skilled migrants and ‘lower-skilled’ (often a reflection of low wages rather than skills) ones who are employed to meet a shorter-term need (for example, seasonal farmworkers). The US, for example, has an H-1B visa for skilled migrants, commonly used for hires in tech, finance and medicine, which is a ‘dual intent’ visa (meaning that the worker has an option to apply for permanent settlement via a Green Card further down the line). Lower-skilled workers, on the other hand, are admitted under the H-2 visa, which has a number of striking similarities to the Gulf’s kafala system, with a worker’s right to remain in the country strictly tied to a specific employer and job.

But there are some critical differences between the H-2 visas and the kafala system. Migrant workers on H-2 visas (H-2A for agricultural workers, H-2B for non-agricultural workers) are generally not allowed to switch jobs during their stay in the US, but there are no penalties for absconding if they decide to leave their job before their contract is up, and employers have no rights to obstruct their departure from the country. Workers who leave early are also legally entitled to payment for the work that they have already completed.

In the Gulf, the framework is similar for nearly all workers regardless of profession or skill level, with only very limited exceptions, the GCC’s treatment of migrant workers as temporary creates precarity for migrant workers and a power imbalance in the employer-employee relationship. This is especially acute for low-wage workers who often pay hefty recruitment fees, getting into debt to do so even before they leave their home countries. Domestic workers, living in private homes where they are cut off from the rest of society, are particularly disempowered by the system.

Exploitation rife across the world

Migrant-Rights.org surveyed the way that other countries manage labour migration, specifically at lower-waged end of the spectrum, to see if there are examples of foreign workers being afforded greater flexibility, stability, and more comprehensive labour rights than in the GCC.

Unfortunately, many of the problems associated with the kafala system, such as the inability to change jobs easily and scarcity of workers’ rights, are also present in other temporary migration schemes around the world. New Zealand’s guest worker programme for agricultural workers, for example, has long come under fire from human rights advocates, while Japan’s ‘intern’ programme, billed as a form of technical assistance for upskilling workers from developing countries in Asia, has been dogged by a string of scandals involving abuse, harassment, and lethal workplace accidents.

A bright spot, though, is Latin America. In countries including Chile and Argentina, migrant workers are permitted to enter the country on a temporary visa to seek employment and have a comparatively wide range of rights and protections enshrined in labour law. In Chile (on paper at least) migrant workers who are documented have the option to apply for citizenship after five years of permanent residence. However, in practice, migrant workers are often discouraged from pursuing citizenship due to the costs involved, heavy bureaucracy and a lack of will on the part of officials to guide them through a complex application process, according to Megan Ryburn, an academic at the London School of Economics.

Kafala by another name?

Some of the stories of the treatment of guest workers under the US’s H-2 visa programme, which brings in around 200,000 workers per year to work in sectors such as agriculture, tourism, seafood-processing and construction, will sound uncomfortably familiar to defenders of migrant workers’ rights in the Gulf.

Workers on an H-2 visa are unable to switch jobs and risk deportation if they complain about unfair labour practices, according to the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC), an American civil rights organisation. The SPLC was recently successful in suing a company providing labour for sugarcane farmers for cheating Mexican migrant workers out of their wages, forcing them to work and threatening to deport them if they complained.

The UK’s Overseas Domestic Worker Visa, which was amended in 2012 as part of a tightening of immigration rules, links the worker’s permission to remain in the country to their employer. This leaves migrant domestic workers vulnerable to the same kind of abuse that they regularly face in the Gulf countries.

NGO Kalayaan has documented countless instances of abuse of migrant domestic workers, such as Susi (not her real name), a Filipino national who worked as a cleaner and nanny for a family in Qatar, and then found herself in the UK when her employer relocated. She lived in cramped conditions, was denied a day off, had her passport confiscated and was forbidden by her employer from leaving the family home. Eventually, she found her passport while cleaning the house and escaped.

Japan’s Technical Intern Trainee Programme (TITP), billed as a foreign aid programme, came into play in the early 1990s, and was the only way for an ‘unskilled’ migrant worker to live and work in the country. Ostensibly, the programme was meant to give workers from developing countries in Asia the chance to learn a trade by working as an ‘intern’ for a Japanese company for three to five years. However, TITP has come under fire from both local and international human rights defenders after numerous cases of abuse against ‘interns’ have been documented, including withholding of wages, sexual harassment, and even the death of a Cambodian plumber following a racially motivated assault in the workplace.

New Zealand is another country where many temporary worker visas, particularly common for workers in hospitality and agriculture, are tied to an employer. Unfortunately, there have been countless documented cases of abuses of workers on these visas, with migrants in the horticultural sector telling a researcher from the University of Auckland Business School that they felt like “prey” at the hands of their employer.

“Unfortunately, New Zealand has a Kafala-type system of its own where employees are sponsored by their employers,” Nathan Santesso, director at The Worker’s Advocate, an Auckland-based law firm, told MR. “It also makes it very difficult for employees to speak up when there is a problem as the employer can terminate the employment which invalidates the visa and requires them to leave the country.”

However, it is important to mention that, unlike in the Gulf, most countries mentioned in this article have spaces and avenues for labour activists to advocate for workers’ rights - often with tangible success. The Migrant Workers’ Alliance for Change in Canada, for example, scored a victory in 2019 when it secured the right for temporary domestic workers to bring families into the country and to have options to apply for permanent settlement. In the Gulf, unionization is mostly banned and civil society groups are heavily restricted.

US’s H-2 visa programme, which brings in around 200,000 workers per year to work in sectors such as agriculture, tourism, seafood-processing and construction, will sound uncomfortably familiar to defenders of migrant workers’ rights in the Gulf.

Reforms that lead nowhere

In recent instances where governments have made reforms to employer-led migration, such as the UK and Japan, changes either don’t go far enough to protect migrant workers, or the government has failed to implement these reforms in a meaningful way, according to human rights defenders interviewed for this report. This means that migrant workers and guest workers remain just as vulnerable to exploitation and abuse at the hands of their employers as before.

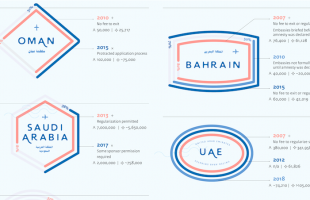

This will be a depressingly familiar scenario for human rights defenders in the Gulf. Countries across the region have reformed aspects of the kafala system in recent years, but have done little to dismantle the oppressive power structures or systemic imbalances that leave migrant workers vulnerable to abuse and exploitation. Even Bahrain’s Flexi-Permit scheme, which came into play in 2017 and allows low-income migrants to effectively “self-sponsor” leaves migrants to contend with high costs and minimal labour protections.

Japan provides another cautionary tale about lacklustre reforms to guest-worker schemes.

The Japanese government rapidly passed a bill in late 2018 that allows migrants to work in unskilled sectors. The result is a new five-year visa, ostensibly an alternative to the TITP, which seems to be aimed at bringing in temporary migrant workers to plug labour shortages. It offers neither a path to citizenship nor the opportunity to bring spouses or family to Japan.

Human rights advocates and legal experts say that the bill is light on details and that it is not clear if it will offer any safeguards against the kind of workplace abuse that proliferated under the TITP.

Saul Takahashi, professor of human rights and peace studies, Osaka Jogakuin University, Japan, says that he is sceptical about whether the bill and the new visa will make any difference to the plight of blue-collar migrant workers in Japan because it suits both the government and corporates to have a ready supply of low-wage workers who have few rights and no path to Japanese citizenship.

“From the outset, the objective of both the TITP and the new system has always been to get cheap labour which we could exploit, plain and simple," he told MR.

“The entire public debate surrounding foreign workers has tended to use the Japanese term ‘foreign human resource’ (as opposed to simply ‘foreign national’), to act as a ‘spigot’ or a ‘regulating valve’ for our companies. In other words, we let in foreigners when it is good for us... When they are no longer of use, we discard them like a used towel, no problem. Certainly, this attitude is not unique to Japan, but it remains a pervasive problem. Let us hope that it changes."

In New Zealand, the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment launched an in-depth review of temporary migration practices in August this year. This will include a number of measures to be rolled out in the coming years, including a phone line for workers to report exploitation and tougher standards for companies that recruit large numbers of migrants. It will also include a new visa for exploited migrant workers “to ensure that they can safely leave exploitative situations without jeopardising their immigration status,” according to the MBIE website.

Domestic Workers in the UK

The UK government took steps to reform the domestic worker visa in 2016, allowing workers to look for alternative employment. However, there is a time limit on seeking another job, and workers can only do this within the duration of their original visa, which is granted for only six months at a time.

In practical terms, this particular reform is of limited use, according to Avril Sharp, legal policy and campaigns officer at Kalayaan.

“This is problematic for many reasons, chiefly that workers escape with months, weeks and sometimes days left on their visa which is not attractive to prospective employers, and many escape without possession of their passport containing their visa that all migrants need, to demonstrate they have the right to reside and work in the UK,” she told MR.

The UK government had also said in 2016 that it would introduce mandatory information sessions for migrant domestic workers residing in the country for more than 42 days, which would make workers aware of their legal rights and of avenues for support. But progress on these sessions seems to have stalled, according to Kalayaan.

Kalayaan not only believes that a better way of managing migration for domestic workers is possible, but is very clear about what this looks like: a return to the pre-2012 ODW visa.

This visa was introduced in 1998 in response to concerns about the poor treatment of domestic workers in private households. It not only allowed domestic workers to change jobs but also offered a pathway to British citizenship. After five years of living in the UK, plus proof of proficiency in the English language, the domestic worker would be eligible to apply for indefinite leave to remain.

If the Gulf countries were to follow the example of Latin America and adopt a more flexible migration policy that broke the link between sponsor/kafeel and worker, it would be an improvement on the current situation, but no silver bullet.

Looking to Latin America

Given the bleak predicament for migrant workers at the ‘lower-skilled’, lower-waged end of the spectrum elsewhere in the world, Latin America perhaps offers a more hopeful example.

In much of Latin America, labour migration occupies a grey area between the temporary and the permanent. Migrants from around the region are relatively free to cross borders without an onerous visa process in order to seek both long – and short-term employment, and unlike the Gulf states, pathways to family reunion and citizenship are technically available.

In much of the region, migrant workers in formal employment can avail themselves of social security and are entitled to benefits such as maternity leave and sick pay.

Latin America has a particularly strong tradition of unionisation and civil society movements. Argentina, for example, has the oldest recorded domestic workers’ union in the world, founded in 1901. During the 20th century, nearly every country in the region established some form of domestic workers’ union, and in 1988, a regional body, Confederación Latinoamericana y del Caribe de Trabajadoras del Hogar, was created. There is also a longstanding tradition of unionization among domestic workers in this part of the world, which seems to have improved the situation of migrant women.

Regional treaties involving freedom of movement mean that migrant workers from neighbouring countries are allowed to move across borders as they please, and seek work after arrival in the country, rather than committing to a contract that ties them to an employer. This also means that family reunification is possible, and that migrant workers can change jobs freely.

For example, citizens of MERCOSUR or Southern Common Market countries (Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay and Uruguay) are allowed to traverse borders without a visa or even a passport – a national ID will suffice. The same freedoms extend to citizens of five associated countries - Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador and Peru.

Recruitment agents do not feature in the migration process for domestic workers in Latin America, unlike in the Gulf countries, where they are the norm, according to Claire Hobden, an ILO expert on domestic labour, speaking in an interview with Reuters. Because of this, domestic workers do not rack up debts at the beginning of the migration process.

But another reason that the plight of migrant workers might be better in Latin American than the GCC comes down to cultural similarities. The vast majority of migrants in Latin America are intra-regional, and already speak the language of their host country [Spanish or Portuguese], Hobden added. This is a far cry from the GCC, where migrant domestic workers from Africa and Asia often lack proficiency in Arabic when they arrive in the country, meaning that they often find themselves socially isolated, unaware of their rights and unable to bargain.

Visas are not generally tied to employers, which means that migrant workers do not run the risk of deportation in the same way that they would in the Gulf countries.

Migration has been comparatively high on the policy agenda for countries in Latin America, partly thanks to a series of regional economic crises (which have acted as push factors for migration) according to Diego Acosta of the European University Institute. The end of a number of military dictatorships and a return to democracy towards the end of the 20th century have led to an increased focus on the role of international law, which has had a knock-on effect on migration policy, he adds.

Countries such as Chile, Argentina, Peru, Paraguay and Colombia have all ratified C189, the International Labour Organisation’s Domestic Workers’ Convention of 2011 – something that the UK and the US, along with all of the Gulf countries, have failed to do. Under the convention, member states must ensure that domestic workers are granted rights such as a full day off each week, possession of their passport and other documents, and the right to a safe, healthy working environment

Other countries have gone further with the national-level legislation. Argentina passed legislation (Law No. 26,844) in 2013 that limits working hours to eight per day and 48 per week and requires employers to provide maternity leave, paid holidays and compensation in the event of layoffs.

And Chile brought in a raft of reforms in 2014 (around the time it signed C189) concerning domestic workers’ pay and rights to rest days. It even became illegal for an employer to make a domestic worker wear a uniform in public.

The fact that migrant workers can regularise their status after entering the country as a tourist has been a broadly positive feature of migration in Chile, said Natalie Sedacca, a Lecturer at the University of Exeter who researches labour rights and human rights relating to migrant domestic workers.

No Utopia

But anti-immigration rhetoric has reared its head, threatening to roll back gains for migrant workers.

In early December 2020, Chilean lawmakers approved a bill that imposes restrictions on how migrant workers enter the country, ostensibly as part of a push by the centre-right government to cut immigration.

“You’d no longer be able to move from tourist status to a work visa. Concerns have been expressed that this could lead to more migrants working irregularly,” Sedacca said in an interview. “Some people have suggested a jobseeker visa that lasts for three months as an alternative to the new system.”

The bill has come under fire from human rights defenders in the region, who say that it falls short in terms of establishing mechanisms for permanent regularization of migrant workers, access to social security benefits and preventing discrimination.

And other countries in the region are by no means perfect. In Argentina, for example, social benefits only extend to migrant domestic workers who are registered (that is to say, recognised by their employers as salaried workers and paying social security contributions), but this only accounts for around 25% of the total, since the vast majority are not formalized, Peter Abrahamson, associate professor of sociology at the University of Copenhagen, argues in a 2017 paper.

“Rights only apply to workers under formal contract; they are not guaranteed for those working informally,” he writes.

More recently, there have been reports of migrant domestic workers in Chile being fired or suspended from their jobs with no compensation during the COVID-19 crisis. And while the presence of a common language puts migrant workers in the region in a stronger position to their counterparts in the GCC, racism against women of indigenous or Afro descent (populations that are overrepresented in domestic work, according to the ILO) is an endemic problem.

Examples for the Gulf?

While Latin America’s treatment of migrant workers on the lower-skilled/lower-paid end of the spectrum is undoubtedly flawed, migration in the region is characterised by freedom of movement and freedom to organize, backed up by national and regional legislation that is, on paper at least, pro-migrant. In this regard, its treatment of migrant workers is considerably more progressive than it is in other parts of the world – including advanced economies such as New Zealand and Japan. The Latin American immigration process is less burdensome for the migrant worker, and a long history of unionisation appears to have improved the lot of migrant workers. While it is impossible to make a direct comparison between the Gulf and Latin America, the latter undoubtedly offers some positive lessons.

But even so, securing citizenship and accessing benefits associated with residency, such as education and social services, still appears to be a challenge for many migrant workers in the region. This demonstrates that gaining relatively easy entry to a country is only half the battle. The Latin American example is a salutary reminder to labour advocates focused on the Gulf to continue to fight for a migration system that enables migrant workers not just to enter a host country, but to thrive and to gain proper benefits associated with residency once they are there.

If the Gulf countries were to follow the example of Latin America and adopt a more flexible migration policy that broke the link between sponsor/kafeel and worker, it would be an improvement on the current situation, but no silver bullet. Governments of the Gulf countries must address the fundamental disconnect in their approach to migration, in which their long-term dependency on foreign labour is framed as a temporary phenomenon. The Gulf countries have been using various forms of migrant labour since the 19th century, and there are no signs to suggest that their dependence on foreign-born workers will decrease in a meaningful way any time soon. While this cognitive dissonance persists, migrant workers in the Gulf states will continue to be regarded by governments, companies and households as an infinitely disposable and renewable resource. In this regard, while the experiences of other migrant-receiving countries around the world can offer useful examples (and cautionary tales) on how to provide fairer and more dignified conditions for workers, the Gulf countries stand in a class of their own when it comes to their level of long-term dependency on migrant labour – and their own reluctance to acknowledge it.