UAE not “making it happen” for its migrants

As parts of the country begin to re-open, low-income migrants are still bearing the brunt of the economic crisis.

Cities in the UAE were amongst the first in the Gulf to announce lockdown orders and shut its borders. It’s now the first to slowly reopen as well, an apparent sign that the situation is improving. But less clear is how the country’s migrant worker population, who account for 80% of the country’s 9.6 million residents and 90% of its workforce, is faring. Low-income migrant workers have not only been hit hardest by the closure of businesses and loss of daily wages from stay-at-home orders but some also report struggling to obtain adequate medical care.

Financial fallout threatens food and shelter

A number of workers told Migrant-Rights.org that they have been unable to buy food and pay rent due to fallout from the pandemic. Some of them were daily wage earners, like cleaners, who depend on moving freely to earn money, while others were employees of non-essential businesses that were ordered to close. A number of workers also had pre-existing wage and employment issues that have been exacerbated by the crisis; government complaints offices have been closed, and though only complaint systems are open, responses remain too slow to be effective.

Many lower-income migrants live in sublet properties, where they pay rent to another migrant and share cramped quarters. In other situations, migrant middlemen manage residential apartment rentals that function as labour accommodation for an Emirati landlord. The arrangement may involve only renting bed space or may include access to the kitchen. In either case, the resident’s interaction is most often with another migrant, who depends on this rent for their own survival.

Dubai has issued a suspension of eviction judgements in both residential and commercial facilities, but low-income workers often do not have the standing to claim these rights. With no suspension of actual rental fees, landlords routinely threaten eviction. There are no homeless shelters for workers to turn to, and embassies and charities have been overwhelmed by the sharp rise in need. An official from one embassy told Migrant-Rights.org that while their shelter is still operating, they are not accepting many new cases due to fear of infection. Government shelters for victims of domestic violence and trafficking had also temporarily closed.

The diaspora associations that typically provide relief also struggle to respond to the large volume of cases while navigating stay-at-home orders and quarantines. The easing of mobility restrictions and reopening of some businesses this week may return some workers to employment, and reduce logistical barriers to providing support. However, a large number of migrants will remain out of work owing to ongoing closures in the hospitality and other sectors hit hard by the crisis. The financial impact on migrant workers will continue to reverberate even as the economy reopens, a reality reflected in the Resolution No. 279 of 2020 of the Ministry of Human Resources and Emiratisation (MOHRE) which allows companies to unilaterally modify contracts for non-nationals alone; though the text of the resolution states that employers and employees should “mutually agree” to unpaid leave or reduction in salary, most workers are not in a position to negotiate.

Unequal Access to Health Care and Underreporting

There are reported health disparities in the treatment of COVID patients as well; while testing and treatment are free, lower-income migrants seem to have reduced access to care.

In one case, a group of workers who tested positive for the virus were told to self-quarantine in their room. While they became increasingly sicker and found it difficult to breathe for days, health officials would still not take them to the hospital. According to sources on ground, nationals who fall ill with the virus are immediately taken into facilities for treatment, no matter the severity of their symptoms.

The country has administered one million tests, covering a little over 10% of the population so far and has reported 100 deaths and 9,813 cases as of 26 April.

But the high rates of COVID19 among migrants who have returned to origin countries from the Gulf indicates that the official statistics may not capture an accurate picture. As MR has reported previously, the crowded conditions that many migrants live and work in expose them to high risk of infection. Furthermore, migrant make up the vast majority of essential workers who continue to work.

Repatriation

Visas have been extended automatically to the end of 2020 for all foreigners whose visas would have expired after 1 March, but efforts are underway to repatriate thousands of workers who are now out of work. Some origin countries are resisting these efforts, as they are either under a lockdown themselves and are unwilling to open airports, or they lack the capacity to test, quarantine, and provide for a large influx of people. Emirati officials have threatened repercussions for origin countries that do not cooperate, including “ future restrictions on the recruitment of workers from these countries and activating the "quota" system in recruitment operations. The options also include suspending memoranda of understanding (MoU) signed between the ministry and concerned authorities in these countries”.

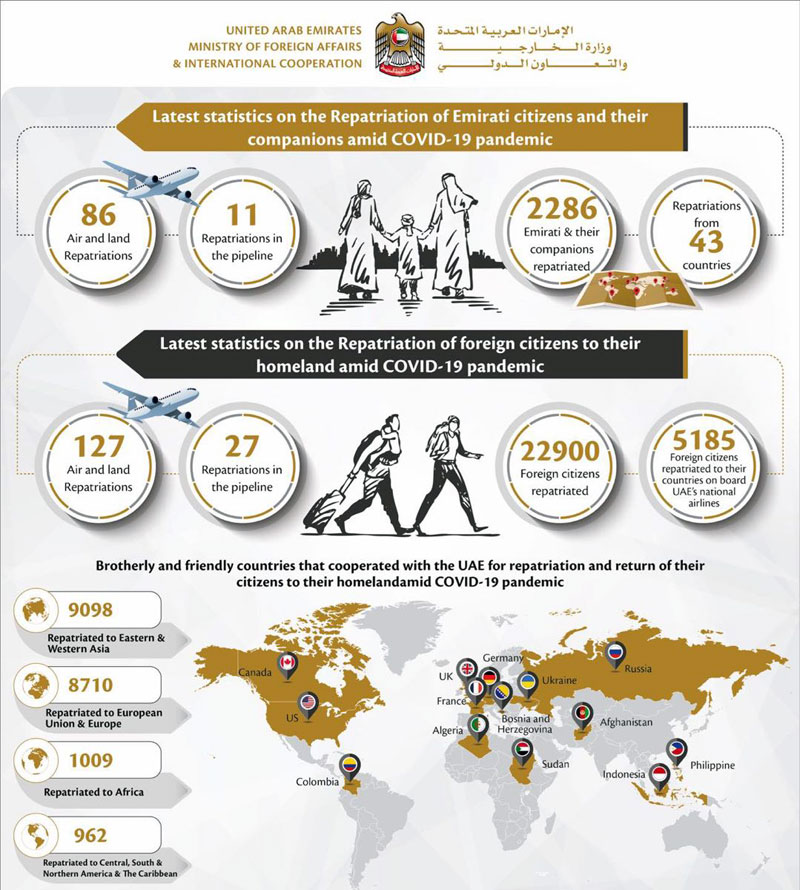

Almost 30,000 foreign citizens have already been repatriated, almost half of them returning to Asia and Africa. An official infographic released by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs & International Cooperation pointedly refers to these recipient countries as “brotherly and friendly,” for their cooperation. Authorities are also coordinating the return of Pakistani workers this week; over 40,000 migrants registered with the Pakistani embassy, though it’s unclear if all will be returning home. With the resumption of a few flights this week and re-opening of immigration offices, some embassies are working to repatriate stranded citizens and others who want to leave.

Visit visa holders

In most cases, the UAE allows for a visit visa to be easily converted into a work visa. This has been an advantage in the past as it allows workers to explore the labour market and scout for a job while in the country, instead of entering into a contract from abroad. However, it also exposes workers to a significant risk of trafficking. Workers can be lured in with a promise of a job on visit visas – with many not able to distinguish a work visa from a tourist visa – and end up stranded without a job, as Migant-Rights.org has recently reported.

While visas have been extended until the end of the year for all whose visas expired after 1 March, migrant workers visas nonetheless face a difficult way forward. Those deceived by fake or misleading job offers have to figure out rent, food, and basic needs for themselves. Government office closures are slowing an already complicated complaints process, which does not consider their complaints as labour violations since the migrants are not on work visas.

‘Essential’ work and Sectoral Regulations

Dubai’s economic department has released protocols and restrictions specific to the construction sector (which is considered a vital sector), which includes mandatory PPE. It’s unclear how this vital safety equipment will be balanced against the country’s high temperatures.

Importantly, specific recommendations are also provided for domestic workers. Domestic workers should be given protective equipment if they must interact with anyone outside of the home or handle packages and deliveries. Tadbeer centres, which provide domestic recruitment and services, also no longer offer live-out arrangements. Live-in domestic workers can still be hired.

The federal nature of the UAE, with seven emirates, in addition to the many free zones each with its own legislation, regulations and jurisdiction, makes it very difficult to apply a uniform Covid19 strategy.