In a comprehensive report on wage theft in Qatar, Human Rights Watch highlights the scale of violations and the ineffectiveness of the Wage Protection System (WPS) and justice mechanisms in holding employers responsible.

The report, How Can We Work Without Wages?’: Salary Abuses Facing Migrant Workers Ahead of Qatar’s FIFA World Cup 2022, in which 93 workers were interviewed said:

Fifty-nine workers said their wages had been delayed, withheld, or not paid; 9 workers said they had not been paid because employers said they didn’t have enough clients; 55 said they weren’t paid for overtime even though they worked more than 10 hours a day; and 13 said their employers had replaced their original employment contract with one favoring employers. Twenty said they didn’t receive mandatory end-of-service benefits; and 12 said employers made arbitrary deductions from their salaries.

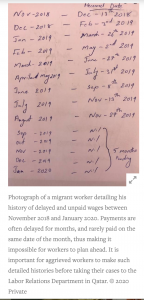

HRW also underscores the progressive delays in salaries, which invariably results in total non-payment, as an indicator of how businesses manoeuver the WPS to their advantage.

The report mentions that “Wage abuses are also driven by deceptive recruitment practices both in Qatar and in the workers’ home countries that require them to pay between about US$700 and $2,600 to secure jobs in Qatar. By the time workers arrive in Qatar, they are already indebted and trapped in jobs that often pay less than promised. Human Rights Watch found that 72 of the workers interviewed had taken loans to pay recruitment fees. Business practices, including the so-called “pay when paid” clause, worsen the wage abuse. These practices allow subcontractors that have not been paid to delay payments to workers.”

Worker testimonies demonstrate the difficulties they face in accessing justice in Qatar.

“Since August 2019, I have been waiting for money,” said a 34-year-old engineer who went to labor court over 7 months of unpaid wages and who has been borrowing money from friends in Qatar to send to his family in Nepal. He first went to court a year ago and is still waiting for his payments: “I am starving since I don’t even have money for food. How will I pay back my loans if I don’t get my salary [through the legal process]? Sometimes I think suicide is my only option.”

The report also carries the first-person account of a Kenyan worker struggling to recoup his wages, which can be read here.

“My workmates encourage me when I am at my lowest points. We understand the systematic challenges workers experience daily. The government talks about reforming labor laws but most of it feels like it is only on paper. People on the ground are really suffering and rogue employers are getting away with gross injustices. The class division is stark in Qatar. The country is one of the richest in the world, but it was built and continues to run on the fuel of its migrants. The exploitation and oppression have taken a mental and physical toll on us, but the resolve to improve our lives keeps us going.”

“My workmates encourage me when I am at my lowest points. We understand the systematic challenges workers experience daily. The government talks about reforming labor laws but most of it feels like it is only on paper. People on the ground are really suffering and rogue employers are getting away with gross injustices. The class division is stark in Qatar. The country is one of the richest in the world, but it was built and continues to run on the fuel of its migrants. The exploitation and oppression have taken a mental and physical toll on us, but the resolve to improve our lives keeps us going.”

Some of the recommendations put forward include:

- Amend the labour law to guarantee workers’ right to strike, free association and collective bargaining, including for migrant workers and domestic workers.

- Amend the labor law to include domestic workers [and ensure they] receive the same protections as other workers.

- Amend article 8 of Law no. 21 of 2015 regulating the entry and exit of expatriates and their residence to ensure that the employee is not entirely dependent on the recruiter for a residency permit; and remove the language in article 8 providing the exception of in cases where the worker requests in writing that the employer keep their passport, thus ensuring that workers do not have to hand over their passports to employers in any case whatsoever.

- Decriminalize the act of “absconding” by amending article 11 of Law No. 4 of 2009. The employer should no longer be allowed or required to file a case of “absconding” when a migrant worker chooses to leave their employment. Employers who have placed false “absconding” charges should be denied from sponsoring visas for more migrant workers. Repeal provisions from the Sponsorship Law that penalize those who shelter “absconding” workers.

- Introduce and pass prompt payment legislation requiring all public-sector clients to pay the principal contractor within 30 days of the valuation date. Include a requirement that interest is made compulsory and automatic on late payment.