GCC states must ensure all residents have access to Covid-19 vaccines

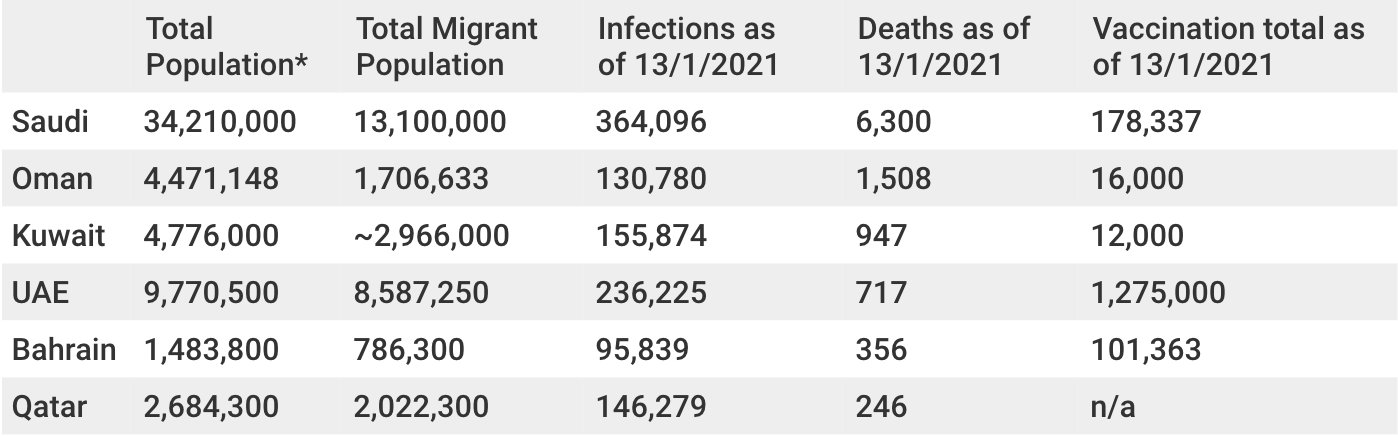

As vaccine drives in the Gulf kick-off, it is critical that plans include migrant workers’ access to registration and appointments.

All GCC countries will provide Covid-19 vaccinations to citizens and non-citizen residents free of charge. Given the large proportion of migrant workers in the region, this is a welcome move both from a humanitarian and public health standpoint. Though details of vaccination plans remain unclear, there are a number of measures GCC states should take to ensure that migrant workers enjoy equitable access to the vaccine.

None of the GCC states has made the vaccine mandatory, and surveys indicate that segments of the population do not want to be vaccinated at this time. This is of particular concern for domestic workers who may be forced to work in unvaccinated households, and whose access to the vaccine is determined by the employer, who controls their freedom of movement and access to information. Alongside the measures noted below, it is critical that workers have agency over their own health, including the right to leave unsafe working environments.

Registering and determining priority

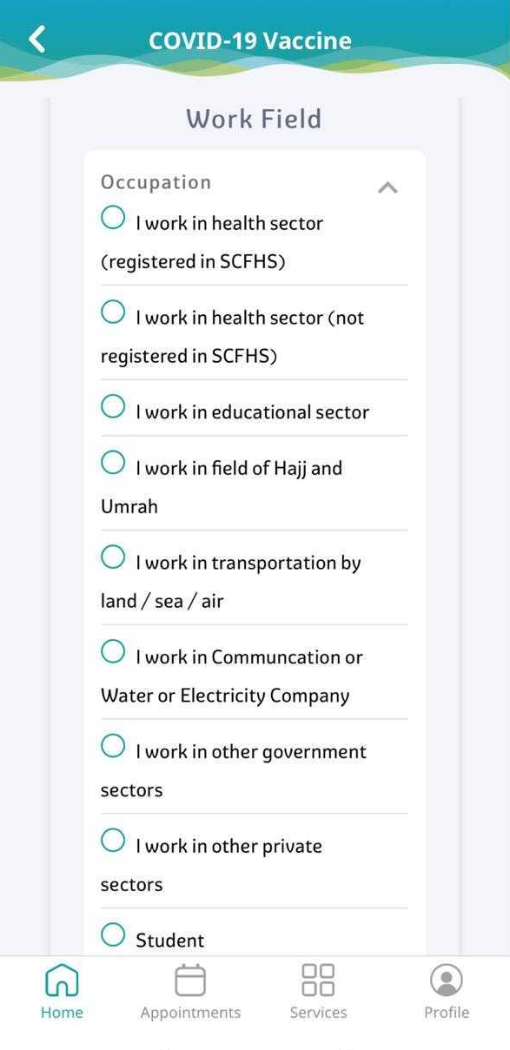

The registration process is almost exclusively online, through Ministry of Health websites or newly released apps. Questions answered during registration determine an individual’s priority to receive the vaccine, and therefore it is critical the process is made accessible as early as possible. Currently, all online forms are in only English and Arabic, neither of which are the primary languages spoken by workers. Those without access to their residency documents, including irregular workers, may be unable to register and risk exclusion. It is critical that these platforms are translated into workers languages and permit identity verification through multiple means. Bahrain’s Covid-19 testing procedures, whereby the Ministry of Health issues a temporary ID to undocumented workers to authenticate their identity, offers a good example of best practice that should be adapted into the vaccine rollout.

Recognising that online registration may not be universally accessible, including to those with varying levels of literacy, it is important that states allow in-person registrations as well.

Saudi residents can register for the vaccine through the Sehhaty app.

Most of the region’s tech and non-tech responses to the pandemic have excluded migrant workers in similar ways, either designed to do so intentionally or without keeping their needs in mind. The likelihood that the systems designed to determine vaccine priority will also be exclusionary seems high. The vaccination priority is similar to most countries, with the vulnerable, elderly, and frontline workers receiving the first phase of doses. However, in practice, the procedures appear slightly less straightforward, as some healthy nationals have already been called up for vaccines during the initial rollout. Officials have also not released detailed information as to how “vulnerable workers” are defined. With economies re-opening, migrant workers in transportation, grocery stores, cleaning services and other sectors with increased exposure to infections face significant risk, yet it is unclear if they will be eligible for early doses.

Furthermore, the ability to furnish the information used to determine priority is largely tied to an individual’s socioeconomic status, as Ruth Faden, founder of the Johns Hopkins Berman Institute of Bioethics, tells Wired magazine. Migrant populations are less likely to have records which substantiate their medical history and vulnerability, particularly if their healthcare needs have been neglected, which is often the case for low-income migrant workers. Speaking in the context of algorithms used by Saudi Arabia to determine prioritisation, Faden notes that a hybrid online/offline approach is critical for addressing these built-in biases.

The emirate of Ajman serves as a good practice example. In partnership with the Ministry of Health, the Indian Association Ajman community hall will provide vaccinations with no prior appointment required (The UAE currently has the second-highest vaccination rate in the world). Similar cooperation with community associations and embassies is key to reaching a large migrant worker population.

Barriers to Access

It is also important that health authorities address other obstacles workers are likely to face in receiving the vaccines, such as transportation costs and issues taking time off work. Strong messaging to employers is important to ensure migrant workers are provided time off to obtain the vaccine, and sick leave for those who experience side effects, without penalty. This is especially important to ensure that workers can access the second dose of their vaccine at the appropriate time.

Providing the vaccine in non-centralised locations is also key. Kuwait and Bahrain currently have mobile vaccination units for those unable to leave their homes, and similar concepts should be used to access workers in remote locations.

Vulnerable groups

Undocumented workers may be especially vulnerable to the virus, in part because many lack regular medical care, but it is unclear if they will be able to access the vaccine in most Gulf states. In general, registration and the appointment day requires a valid national ID and health card, which undocumented workers are unlikely to possess. So far, only Kuwait has explicitly indicated that undocumented residents will be eligible.

It is critical that migrants with an irregular status can receive the vaccine, and that they are assured they will not be detained or otherwise penalised when they register or attend their appointment. This ‘firewall’ between medical access and immigration control is critical to safeguarding both the health of migrants and the public at large.

Additionally, migrants in detention centres and prisons are particularly vulnerable to infections and must be prioritised for the vaccine. Processes for these vulnerable groups may not be mainstreamed in the national response policies.

*By last year available

New recruits

Gulf states have begun a new wave of recruitment for various sectors. All of these new hires do go through stringent testing pre-departure and post-arrival. These groups must be immediately included in vaccination drives, even if their visas and IDs take up to three months to be processed.

With Gulf states reopening to business and tourism, it is critical that migrant workers are properly accounted for in planning, coordination, and logistics of vaccination drives. Migrant-Rights.org issues the following recommendations:

- Ensure registration and all messaging is translated into languages common amongst workers, and that in-person registration options are available;

- Work with mobile clinics and companies to ensure that workers who are in distant places can receive the vaccine without an arduous journey;

- Work with community groups and embassies to drive registration and help spread messaging about the vaccine;

- In determining priority, take into account the exposure risk that many migrant workers may face in their working environments;

- Ensure irregular migrants also have access to the vaccine, and ensure they are not penalized for their status;

- Communicate with employers, including fo employers of domestic workers, to safeguard workers’ access to the vaccine;

- Since the vaccine is given in two doses, ensure no migrant is excluded from the second dose;

- Provide regular disaggregated data on vaccination rates of nationals and non-nationals.

For Domestic Workers

- Work with recruitment agents to ensure domestic workers are covered or informed of the vaccination drive;

- Reach out to school PTAs, community groups, and Facebook groups where domestic workers may be active to ensure they are made aware of their right to be vaccinated;

- Work with embassies of countries of origin, by setting up designated days for vaccination, in order to cover domestic workers;

- Primary health care centres, emergency care, paediatric centres must carry multilingual leaflets with information on the virus and vaccination, as these are places domestic workers visit often.