Ghanaian Women Trapped in Kuwait Tell Their Stories

Last May, Migrant-Rights.org spoke to Gloria, a Ghanaian migrant worker who survived abuse and managed to escape Kuwait. Since then, MR has chronicled more stories of Ghanaian women trapped in Kuwait, following false promises of good jobs and salaries. The Gulf's relatively new interest in the African labor market means the recruitment corridor remains poorly organized and easy to exploit. As a result of rampant abuse, Ghana banned its citizens from traveling to Kuwait on a visa-20, the domestic worker's visa, in April 2016. Every month, dozens of women escaping abuse and exploitation in Kuwaiti homes were repatriated. Ghanaian diplomats admit that recruitment should not continue without a bilateral agreement securing workers’ rights. Ghana has no embassy or mission to serve the estimated 5,000 domestic workers in Kuwait, so Ghanaians must contact the embassy in Saudi for help.

Despite the ban, domestic worker recruitment persists as middlemen easily shift go underground with their operations. Ghanaian media has documented several stories of trapped workers in the Gulf, particularly in Kuwait, in which workers report nearly identical patterns of abuse.

False Promises and Exploitation

Stories of exploited and abused Ghanaian women in Kuwait emerged back in 2013 but spiked in 2015 and 2016. In March 2015, local media reported that over 500 Ghanian women were stranded in Kuwait. Ghanian authorities denied such numbers, but many personal stories emerged. Many of these women are educated, skilled, and experienced. They are promised jobs in formal sectors, with decent working hours and living conditions. Instead, they are trapped in household work, sometimes starved, beaten, and sexually abused. They demand to return home after discovering their real jobs. But the agencies tell them they’re trapped, that their families must pay for them to exit, and that they should instead work to save up money to leave. [tweetable] In the first three months of 2015, at least 350 women managed to return to Ghana from Kuwait [/tweetable] , according to Ghana Immigration Service.

Gloria was told that she would be earning a monthly salary of USD 600-800 at a shipping company. She flew in for this opportunity which was advertised in a newspaper. Her sister and friend followed her. Little did she know that the three of them would work as domestic workers, serving big families and prohibited from leaving their employers’ homes. Gloria’s employer told her she must pay her 700 KD to quit, or complete the two-year term for a contract and a job she did not sign up for. Gloria worked from 5 a.m. to midnight everyday; cooking, cleaning, babysitting. No breaks, no days off. Kuwait’s domestic labor law grants rest time and days off, among other rights, but it is only ink on paper. After two months, Gloria could not take it, she used the internet and found a way to escape home, traveling with her sister and friend to the domestic workers’ shelter. Even at the shelter, they were abused. Shelter workers did not attempt to recoup their unpaid salaries or benefits. Read Gloria’s full story here.

Another story involved 18-year-old Maame Yaa who was promised a job at a supermarket, only to find herself isolated in a Kuwaiti household, working as domestic worker. Yaa was taken to the police station after a fight with the employer’s daughter, so the employer took her to the police station and the police ordered the agency to deport her. Instead, the agency ‘mediated’ the situation – telling Yaa she should behave and attempting to convince her employer to take her back. Yaa’s experience with agencies is not abnormal. Rather than creating a safe space for women who have escaped abuse, agencies often keep workers crammed in small rooms and try to scare them into working again. Some deny women food and water.

Yaa did have some luck at the agency; there, she met a Ghanaian man and told him her story. He contacted the embassy in Saudi on her behalf, and the embassy managed to rescue her. Yaa was then able to return home in July 2014, where she recounted her tale and the tale of fellow countrywomen. Two other Ghanaian women trapped at the agency and pregnant. Rape, the Ghanaian ambassador asserts, is also part of the violent pattern that these women are exposed to - another report documents the dozens of Ghanaian women sold into prostitution.

“I was treated like an animal and I was made to serve them like I was a slave”

In May 2015, pictures of 18-year-old Latifa Adams circulated after she was rescued by the Ghanaian embassy. Adams’ “odyssey to modern slavery” started with a job offer to work as a nurse in Kuwait. She would share housing with other Ghanaian women, and a company bus take them from and back to work. When she realized she would instead be working as a maid, she asked to go back home, but her plea fell on deaf ears. On her first day in Kuwait, Latifa found herself sharing a small room at the agency with nine other girls. Every other hour, one of them is taken to her new employer. “They told me I had been sold to a Kuwaiti family to work as a servant.” When she called her Ghanaian recruiter, he told her she “shouldn’t make any fuss.”

Recalling life at her employer’s household, Latifa says “they beat me. They slapped me. They starved me. I was always locked in the house. Even when they went to the bathroom, they took the key with them. The four walls of the house were like a prison.” She was working 20 hours a day. Her duties included everything from washing, cooking, cleaning, and babysitting. No rest, no days off. She couldn’t even use the shower - her employer would fill a small basin for her to bathe with. When the ‘madam’ found cleaning lacking, she beat her with a mop or a hanger. She passed out during one of those assaults. “I was treated like an animal and I was made to serve them like I was a slave,” she says.

Latifa once ran away to the agency, after being slapped and beaten. The agency told her to “be patient” and warned her against running away. When the employer showed up two days later to take her back, he immediately started to beat her up, in front of agency employees, who took no action. Latifa’s “rescue” did not come easy. It only ended because of a kitchen gas explosion, which left her severely burned and bleeding. Her employer’s family did not rush to hospitalize her, though she plead for medical care. Finally taken to the hospital, but her injuries had become so severe that she was transferred to another, where she stayed for 33 days. Latifa endured severe pain, and without anyone to care of her. At that moment, all she wanted was to end her life.

Saudi’s Ghanaian ambassador was informed of Latifa’s case and came to her rescue. According to his statements, the hospital in Kuwait did not even provide her with antibiotics. He arranged for her to go back to Ghana, where she is undergoing surgery from her neck to thighs.

Two months after Latifa’s return, the embassy rescued another woman. She had paid a recruiter to get a job as a personal assistant in Kuwait, and purchased her own ticket. When she arrived at the airport, her passport was seized and she was kept in a room with other women for seven hours until someone from the agency came to pick her up. After two days of trying to call home but failling, she gave in and went to her employer’s house: “When I got to the house, I realized that it was slavery.” She was working 20 hours a day. Luckily she managed to connect her phone to the internet and reached out for help from the community, who put her in touch with the embassy. She was eventually repatriated.

All migrant workers remain vulnerable to contract substitution

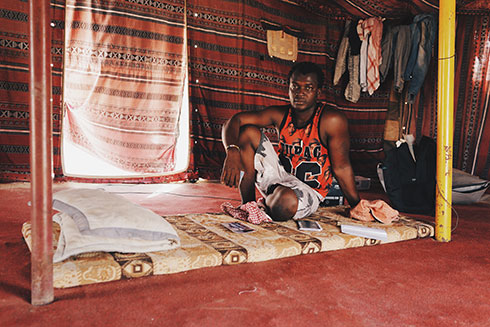

The entrapment of Ghanaians in Kuwait is not limited to women; men, too, are often promised small jobs in companies or as security guards, only to find themselves working as domestic workers – drivers, or much worse, as shepherds in the desert cut off from the world. Shepherds are considered domestic workers by Kuwaiti law, and therefore are not covered by the labor law.

One Ghanaian man, Abdulai, told his story to a Kuwaiti blog, wanting to show people that “slavery still exists.” Back in Ghana, Abdulai made good money teaching English and Math to school kids. His employer tried to withhold months of his payments. He was promised $1000 in salary but only received KWD 70 a month, that’s $230. He has no electricity, living in the open heat which sometimes reaches 60 degrees celsius during summer. He says his co-workers were even beaten before his eyes. Because he can’t change employers nor leave the country without his employer’s permission, Abdulai must endure this exploitation until his two-year contract ends.

The Ghanaian ambassador to Saudi says his embassy receives similar stories from three or four maids every day. He adds: “there exists a significant and pervasive pattern of rape, physical assault and mistreatment of Ghanaian maids that takes place largely with impunity.”