Rarely are migrant workers visible in the glitzy cities they build in the GCC states; and when they are, the sartorial association is typically blue overalls, hard hats or cheap pyjamas that pass off as uniforms.

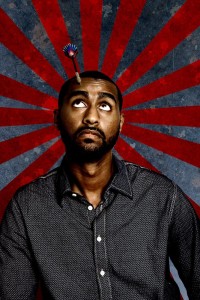

Renowned Doha-based Sudanese artist Khalid Al Baih launched Doha Fashion Fridays (DFF) in 2016 to counter that imagery. Al Baih went to Doha’s Corniche every Friday to take photos of migrant workers enjoying their day off. He captured their fashion sense and their freedom from restrictive work uniforms. When asked about what influenced the project, Al Baih said that he “wanted to work with something I love – style; to battle something I hate – dehumanisation.” He hopes the movement keeps growing and reaches many people.

The Ensaniyat* team in Kuwait and Qatar is continuing Al Baih’s work with his support and mentoring. Kuwait Fashion Fridays was launched on August 4, 2017.

Our goal is to advance Al Baih’s idea of introducing migrant workers, who play a very crucial role in our everyday lives, to Kuwaiti society at large through social media. Also similar to DFF, we wanted to show appreciation for the different fashion styles and personalities that make up our diverse community. Finally, we wanted to create a platform where migrant workers can share their stories, or anything they want, with people they might not have face-to-face conversations with in real life.

I wanted to work with something I love – style; to battle something I hate – dehumanisation

Before starting Fashion Fridays in Kuwait, we carefully planned the theme of our Instagram page, the locations we wanted to visit, and the different nationalities and occupations of workers we wanted to feature. The next and most intriguing step was going out and meeting the workers. As our team consists of Kuwaiti nationals, we thought it would be easy to approach workers in Kuwait City. We quickly realised we were off the mark. The first time we went out, we were avoided by many of the workers who seemed uncomfortable with the idea of a group of 4-5 people were approaching them with notebooks and cameras in their hands, wanting to take pictures of them and asking questions about their jobs and day-to-day lives. This approach was a big mistake, and a learning opportunity for us. We were so focused on getting photos that we forgot to put ourselves in the worker’s shoes and imagine what it might feel like having a group of strangers asking to take our pictures. We decided to change both our approach and the location the next time we went out.

On a Friday, Kuwait City is known for being the place where most workers spend their day off. The church, local markets and restaurants are all located here. This is why, initially, it seemed like the perfect place to start. We realized the area was too crowded when the one worker who eventually agreed to stand for a photo ended up changing his mind when he realised hundreds of other workers around him were staring. So we shifted our attention to quieter areas, such as the church, where we could freely and openly speak to workers, introduce the project and its purpose, and take photos without interruption. We showed the workers our Instagram page, which helped tremendously with our credibility and their comfort. With this new approach, we noticed a significant shift in attitude and reactions after the first couple weeks. Workers now felt much more at ease posing as they pleased and telling us their stories.

We start with warm-up questions – their name, age, and nationality – and then shift to asking about where they work and how many years they’ve been living in Kuwait. Depending on how comfortable they are, we move forward. We ask them if there is anything they would like to share about their life in Kuwait, such as what they like doing during their day off. We make sure that we always give them a chance to add a few sentences about anything they feel is important, and that sometimes opens the door to discussions about their life that are more personal, both in Kuwait or back home.

We now would also like to focus more on stories of migrant workers' personal experiences in Kuwait or of different obstacles they have faced either in their job or simply living in Kuwait as a foreigner. We also plan to feature videos where workers and their employers can share their experiences of working together. Finally, we would also like to shine more light on domestic workers, who are usually harder to spot outside “free” on a Friday or Saturday because even those that do have a day off often aren’t allowed to go outside alone. This might require working closely with sponsors who do provide their domestic worker with their right to a day off and allow them to enjoy it, unchaperoned, as they please.

View the Kuwait Fashion Friday Instagram page here.

*Ensaniyat is a project by Migrant-Rights.org that brings together young adults from Qatar and Kuwait to work on social justice campaigns in their communities and share experiences. This article is written by the Ensaniyat team.

![Image relating to [Stories of Origin] Indian fishermen: Between the devil and the deep sea](https://www.migrant-rights.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Screen-Shot-2018-12-27-at-10.35.49-AM.png)