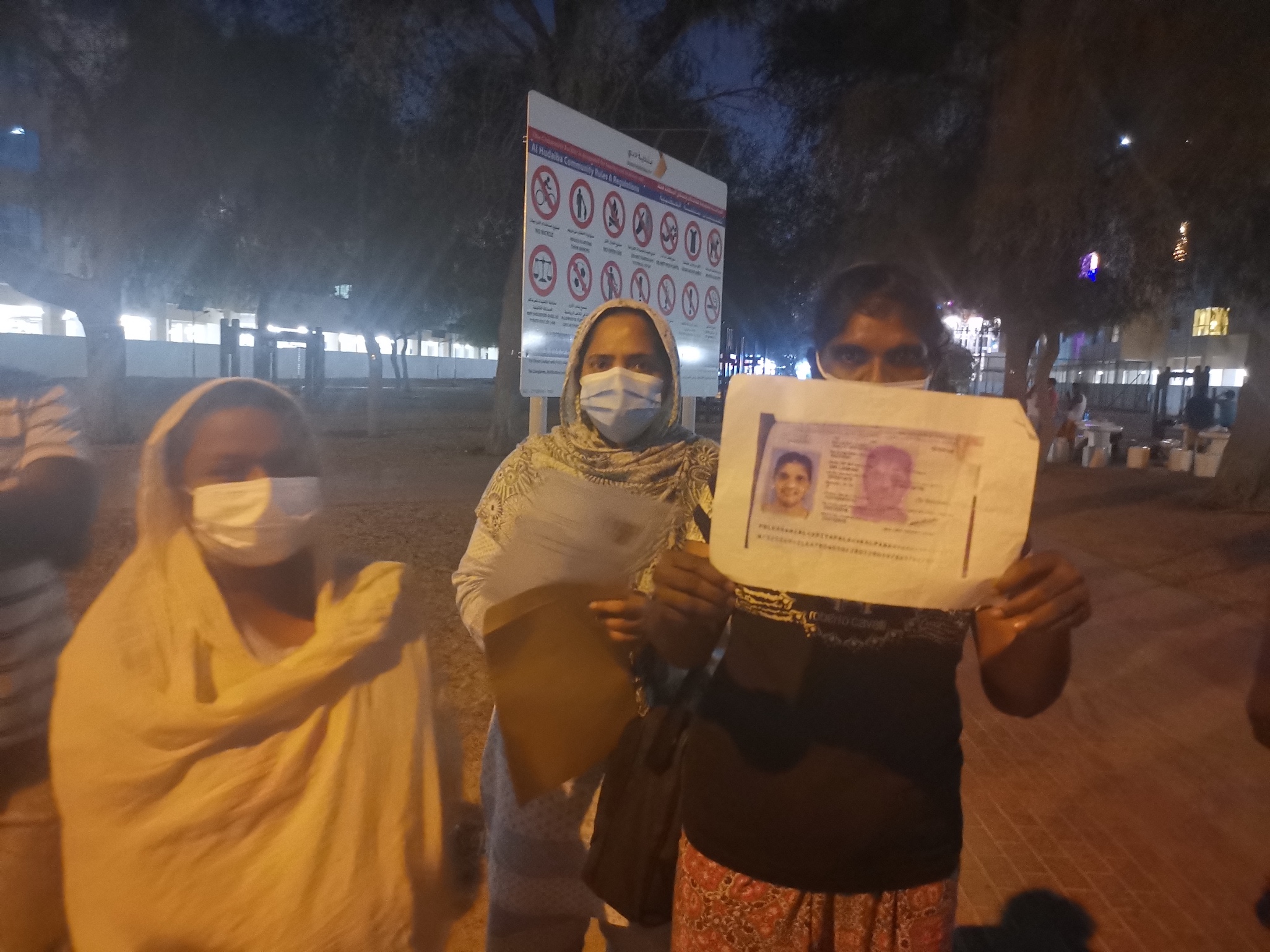

Sri Lankan women are living in a public park, hoping to get on the next repatriation flight.

As economies continue to suffer across the world, hundreds of workers have been rendered homeless in the UAE over the last several months, primarily due to job loss and origin countries’ reluctance to accept repatriations. There has been a systemic failure in the UAE to protect the rights of workers and hold employers accountable for ensuring accommodation and food are taken care of until employees can be repatriated. Even so, new recruitment has already begun. Origin countries have also failed their citizens by not providing adequate resources to their missions – where they exist – to resolve grievances of those stranded. Sri Lankan workers are among those critically affected, in part because the country organises very few return flights each month.

"I wasn’t given any notice or gratuity. I have 30 days to leave the country to avoid being fined but no one is listening to me in the consulate."

According to the International Labour Organisation (ILO) more than 95% of Sri Lankan migrants are employed in low-skilled and labour-intensive jobs across the GCC. In the UAE, Sri Lankans account for 3.2% of the UAE’s population (around 0.3 million). Over 90% of Sri Lankan migrant women work as domestic workers or in low-wage sectors.

“On the morning of 27 October, suddenly my sponsor told me that he will not renew my residence visa,” says Riya, a domestic worker who had worked for many years in Umm Al Quwain. “I wasn’t given any notice or gratuity. I have 30 days to leave the country to avoid being fined but no one is listening to me in the consulate. They have too many people coming to them every day, they said.”

PE, another Sri Lankan national who had worked for a leading e-commerce company for almost five years. “Unfortunately, our services were made redundant in March 2020 due to Covid-19 and cost-cutting. I have been searching for a job since, but nothing has worked out.” PE’s employer gave him a three month grace period for his and his wife’s visa. It was ultimately cancelled in June 2020. “We planned to move back home and registered with the consulate in person as the link on the website didn’t work for them, but borders were closed,” he says. The UAE had at that point waived overstay fines until October 2020 (fines are now waived until the end of the year), which gave PE more time to look for a job. He received a job offer in mid-September. “And at the same time, I got a message from the consulate for PCR testing for a repatriation flight. However, on the assurance of the human resources manager of my new employer, I cancelled my repatriation flight and joined the company.”

In an unfortunate turn of events, PE – along with many other employees – was made redundant again within three weeks of joining, before his employment visa was even processed. “The last day of my visa extension period was 3 October. Now my previous company is calling and threatening to file an absconding case against me unless I change the status of my visa. I don’t know what to do now.”

Workers who came on tourist visas are in an especially difficult spot. Before the pandemic, most had taken loans from family and friends to fund their travel and accommodation with the hope of finding a job. Unsurprisingly, most have not been able to find employment and are stranded due to lack of funds, closed borders, and limited support from their embassy.

“I am hoping that someone would read this and help us to get back to Sri Lanka. I would like to stay anonymous as revealing my details could cause us problems,” says RS who came to Dubai eight months ago on a visit visa. RS managed to stay with friends and survived on borrowed money. “But that was not sustainable,” he says. “I approached the consulate hoping to be repatriated, but the officials there blamed us for coming to Dubai on a visit visa.”

Having lost their accommodation, with no food or water, RS and others have been sleeping in the park. “Every morning we go to the consulate hoping that we could get our name on the repatriation list, only to be shooed away by the consulate officials,” RS says. “I am helpless. I have no place to stay, have not eaten in days and our consulate is not helping. I hope by sharing my story we get the help we needed.”

RS is just one of many workers – from countries such as Ghana and Nigeria – living in public parks, surviving mainly with the help of volunteers and occasionally host governments. Various embassies and consulates have dealt with repatriation needs of their citizens in different ways.

For months, Sri Lankans in need of help and repatriation have slept in public parks near the consulate in Dubai. Many of them were initially provided accommodation by the Dubai government, a locally registered NGO, and volunteers. The treatment, however, by their home government and consulate has been callous and chaotic, according to those stranded. Though they picked up breakfast or lunch parcels from the consulate, they mostly relied on volunteers for food and other basic necessities and received no accommodation support. These workers included women who often had no access to toilets and showers. Many of them tried to go to nearby shops, restaurants and service stations but were turned away due to Covid restrictions.

Consulate staff, when approached, were very reluctant to respond and give clear answers regarding accommodation arrangements and repatriation flights. The oft-repeated explanation was both the lack of funds and the Sri Lankan government’s reluctance to resume repatriation flights, in order to contain the number of Covid cases within the country. They also maintain that only those who came here on proper work visas and are registered with the ministry of foreign affairs can apply for repatriation.

Recently, another repatriation flight has been announced but many people on the tentative list have no money to purchase tickets, having been jobless for months. Unlike past flights, the consulate now requires proof of funds – either from migrants themselves or through a volunteer or donor – to be included on the list.

“I am helpless. I have no place to stay, have not eaten in days and our consulate is not helping. I hope by sharing my story we get the help we needed.”

Though countries of origin and destination have deflected responsibility for migrant workers throughout the pandemic, there are clear measures both must take to protect their rights and wellbeing. Destination governments must ensure workers’ access to healthcare, enforce employers’ obligations in regards to food, housing, and wages, and provide shelter to those made homeless by the pandemic. They must also coordinate with origin countries to ensure workers can easily leave the country. Origin countries have an obligation to fill the gaps that destination governments leave behind and to facilitate the efficient departure of workers.

Both governments should:

- Arrange for affordable and/or free shelter for workers;

- Allow all workers, regardless of visa status, to register for repatriation flights;

- Provide tickets for workers who cannot afford them;

- Ensure all dues are paid to departing workers, failing which the embassy is given a power of attorney to recoup from employers;

- Provide clear communication to workers in distress.