“I am not a business lady”

Bahrain’s anti-sex work policies lead to abuse, arbitrary arrest, and deportation of migrant women who aren’t engaged in prostitution

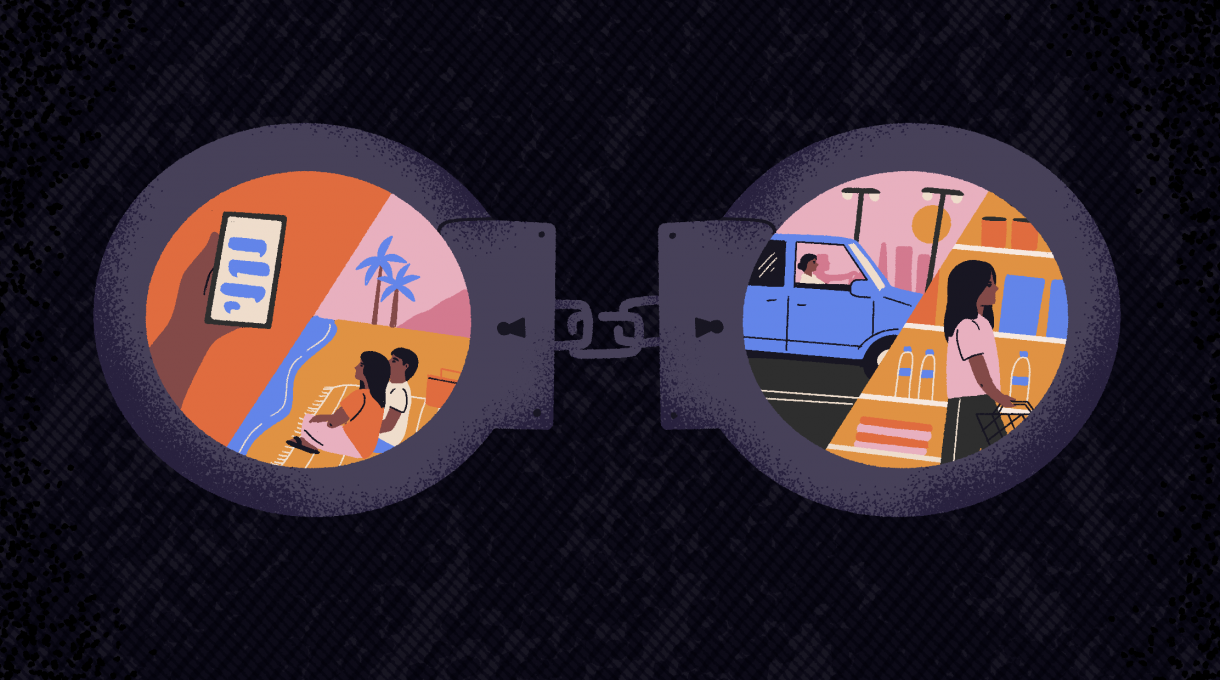

Of the many negative consequences that come with the criminalization of sex work in Bahrain – which includes rendering sex workers vulnerable to violence and without access to proper health care or justice – is the detention and deportation of migrant women who are not even engaged in sex work. Sexualisation of low-income migrant women and domestic workers in particular means their presence anywhere outside of the narrow constraints of ‘work’ is considered suspect. The stereotyping plays out on racial and class lines, with the more affluent escaping the highhanded treatment of authorities in similar situations.

In the past year alone, Migrant-Rights.Org documented several cases of migrant women who were arbitrarily arrested and falsely accused of prostitution, despite clear evidence to the contrary. MR interviewed several women who said they were abused by the police, were not provided with translation services or lawyers and were eventually deported without due process.

The night before her day-off, Jay, a Kenyan waitress who works full-time in a hotel in Bahrain, visited her friend at her house in Qudaibiya for a birthday celebration. As it got late, she decided to sleep over instead of walking back home. The next morning, her friend left home early for her work shift and as Jay was waking up she heard a loud bang on the door – the whole building was raided by the police.

“They asked me what I was doing there, I told them it’s my friend’s place and I was sleeping over, they immediately asked for my CPR (ID) and took my phone from me. The officer asked me to unlock my phone and started to look into my pictures and messages… another officer was looking around the house and collecting empty bottles of alcohol.” After a few minutes, Jay heard a phrase from the police officer that many migrant women like her hear before getting arrested: “you’re a business-lady”.

“Business-lady” or “business-girl” is a term authorities in Bahrain use to refer to sex workers. Jay was told to quickly collect her belongings and was taken to the Central Investigation Department (CID) in Adliya, along with several other women for interrogation.

“I was really scared, the police were very aggressive. I didn’t know what to do, I told them repeatedly that I work for a hotel, I told them to check my visa, that it’s under the hotel name, but they refused to listen and insisted that I was a “business lady” because there was alcohol in my friend’s place and I had Tinder (a dating app) in my phone.” Alcohol, Tinder, and sex outside of marriage are not illegal in Bahrain.

Jay told MR that she was forced to confess that she was a sex worker, “I couldn’t understand most of what they were saying, they were shouting at me and forcing me to sign a paper in Arabic which I couldn’t understand…they didn’t even provide any translation.”

All of the migrant women that MR spoke to said that translators were not provided to them during the investigations at CID’s Anti-human Trafficking and the Protection of Public Morals Directorate.

In a letter sent to the High Court of Appeal which was reviewed by MR, a lawyer that represented one of the women argued that confessions cannot be valid if the accused had no knowledge of reading and writing in Arabic and no translation was provided. The appeal was nevertheless rejected by the court.

Above audio: Mary says the CID coerced her to sign papers in Arabic that she did not understand but learnt later that it was a confession of her being a was a sex worker. The judge ruled that she be deported due to this false and forced confession.

After being forced to sign a few documents, Jay was taken to the women’s detention centre in Al-Hidd where she was eventually deported. Her experience is not a one-off occurrence. In another case of discriminatory policing and profiling, Ell, who works as a waitress, was arbitrarily arrested when her manager dropped her home following a midnight shift.

“At the checkpoint, they asked me to get off the car, they asked my Indian manager to go away, took me into the minibus and told me to unlock my phone… one of the police officers told me ‘I know you are a business lady.’ I didn’t know what it meant then and when I loudly said that I didn’t do anything, the police officer slapped me and told me that they are taking me with them to the CID.”

Just like Jay, Ell went through the same abuse at the CID. “I begged them to let me go, I told them I am married, I have a three-month-old baby. My manager came again to assure them I work with them and my husband came with my baby to show them I did nothing wrong, but the CID ignored them and insisted I was a ‘business lady’.”

Ell was then taken to the deportation centre but because her baby who was with her was undocumented (due in part to the complicated paperwork involved), the authorities were not able to deport her. After a couple of months and several appeals by civil society organisations Ell was finally released.

“The only reason I was not deported was because of my baby,” she said.

Based on the cases MR has reviewed, there is a clear pattern of profiling women of African and Asian background. The majority of these cases are in areas such as Gudaibiya, a cosmopolitan neighbourhood in Manama that is home to a large number of low-income migrant communities from Asia and Africa.

Above audio: Abi, who was detained and deported by the police, describes how the police threatened her with a jail term if she didn’t confess to being a prostitute. The woman describes how she was sent to the deportation centre even though she pleaded not guilty to the judge.

An African embassy representative in Bahrain told MR, “many women from my country are wrongly arrested for being a ‘business lady’ and sometimes they were arrested only for drinking alcohol, being at the beach with their partner, or for having dating apps (which are legal to download) on their phone.”

A lawyer in Bahrain told MR; “We have received several cases where innocent women were arrested randomly and accused of being a prostitute.… In most cases, we were unable to win an appeal because the judges always take the side of whatever the police say, even if what they say is clearly artificial.”

“Now, and especially since the Covid pandemic, we are struggling to contact the public prosecution to enquire about a specific case and rarely do they respond to our official letters to take the cases to competent court (المحكمة المختصة) for reconsideration.”

Migrant-Rights.Org spoke to the employer of an Ethiopian worker who was arrested next to the cold store in Qudaibiya “After they arrested her, they called me and told me to bring her passport, I said why? They said that there is a deportation ruling against her. I said based on what? They replied there is a prostitution case against her. I said, ‘Prostitution? And you have taken her from the cold store!”

The employer refused to turn in her passport, in an unsuccessful effort to stop her deportation.

“When I went to the immigration and saw her report, all kinds of stories were written; that she confessed of prostitution, and she was making this many dinars with this many men etc. It was all made up and at the end, she was deported.”

Above audio: Kay recounts when she was taken to the CID office she was accused of being a sex worker without evidence and was taken to the deportation centre without appearing in court, even though her sponsor insisted to the CID that she was not a prostitute and that she worked for him.

The racial profiling of migrant women and false prostitution charges are not arbitrary decisions of individual officials. There are systemic issues that demand an urgent and critical review: the profiling of certain groups, lack of police accountability, lack of due process in investigations, and several barriers to justice, including language and legal representation.

That anti-human trafficking and ‘public moral’ is considered the responsibility of a single agency seems to take lightly the many different aspects of human trafficking, most important of which is that if women are trafficked for sex work they cannot be treated as criminals. The current practices seem to be more in keeping with the moral policing of women than in any protection.

Recommendations:

- Police must be given gender-sensitive training.

- Provide free interpretation and translation of all police and judicial proceedings.

- Provide migrant women with free legal aid and create an environment that fosters judicial impartiality.

- Decriminalise sex work – criminalising sex work not only creates a harmful relationship between sex workers and police authorities but also as studies have shown, renders sex workers vulnerable to abuse and offers impunity to law enforcement authorities to perpetrate violence and abuse against anyone deemed a sex worker.

* all names changed to protect the identity of the women