Huge recruitment fees charged for jobs in the Gulf; Qatar recruiters accused of demanding the highest commissions

Migrant workers and recruitment agents from Kenya say the cost of recruitment to the Gulf, particularly Qatar, has risen dramatically in the last five years. Several individual agents and associations based in Nairobi and Mombasa claim that human resource (HR) consultants recruiting for Qatar-based companies demand exorbitant fees, as well as business class fares and five-star accommodations for the HR consultants or officers who travel to Kenya to conduct interviews.

Migrant-Rights.Org reviewed Request for Proposals (RFPs), job orders, email conversations between recruiters and agents, and WhatsApp messages that all support these claims.

For over a decade now, the campaign for ethical recruitment across origin countries has attracted millions of dollars in funding, with innumerable iterations and versions of projects exploring ethical recruitment models. The Employer Pay’s Principle – according to which “no worker should pay for a job – the costs of recruitment should be borne not by the worker but by the employer” – has been widely accepted as best practice. However, legislation in the GCC states only adheres to this principle on paper. In practice, few mechanisms are in place to ensure that employers do actually pay, and instead responsibility for eradicating corruption in the recruitment process is deflected to Asian and African origin countries. What states and ethical recruitment programmes ignore is that a significant sum of what agencies in countries of origin charge appears to be syphoned back to companies or recruiters in the GCC, according to documents reviewed by MR.

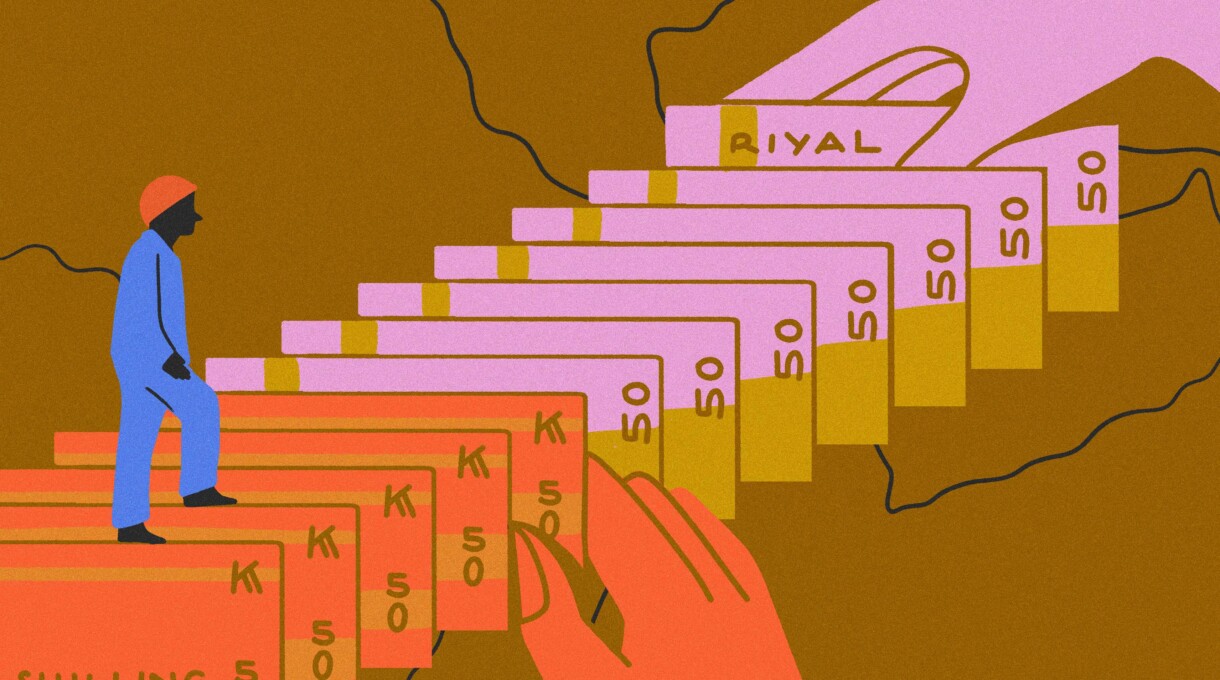

On an average, workers pay between US$900 and 1200 for a job. Kenya permits charging workers not more than one month’s proposed salary. This is legal, though it contravenes the fair recruitment guidelines. In Qatar, monthly salaries are roughly between the minimum wage of US$275 and up to US$320 in the security sector. Any fees charged over and above that are divided between recruiters in destination and recruiters (For more details see Processing Costs and What is Fair and Ethical Recruitment?)

The head of the Kenya Association of Private Employment Agencies (KAPEA), Mwalimu Mwaguzo, stresses that for the recruitment process to be ethical, agents should be able to work directly with the company or final employer. “That is not the case now. Now we work with HR companies. If there’s a job order for 100 workers, then we have to pay on an average US$400 plus a ticket for each worker.”

He recalls a senior Emirati government official on a visit to Kenya telling the agents that it is illegal for companies to charge agents or workers for job orders, and to inform them if such demands are made so that they could take action. “Well, we did reach out a few times, but there was no response.”

Charging workers recruitment fees is illegal in most GCC states, but regulations are applied narrowly — and ineffectively — to any transactions that might take place in destination countries. Fees paid at origin are considered out of their jurisdiction. However, there is scant due diligence done on where fees charged in origin may end up, including in the coffers of businesses or recruiters based at destination. A few big organisations do claim to reimburse recruitment fees, but this usually requires workers to provide some kind of invoice or paper trail, which is rarely available. In general, GCC states provide poor grievance mechanisms to workers charged illegal fees.

An emerging and worrying trend

The highest demand for Kenyan workers is from Saudi Arabia and Qatar, followed by the UAE and Kuwait. “Each of them has a different practice. In Saudi, many companies don’t charge, though they may ask us to pay for the tickets. Qatar, every single one, except Mowasalat (state-owned transport corporation), charges us. And they don’t give an invoice for the payment. They are very clear from the beginning that we can’t ask for any proof of our payment. And if you protest or insist, they just go to another agent,” complains one agent, who recruits workers from in and around Mombasa, primarily for the security sector. They add, “The representatives of these HR companies tend to be Indians, Sudanese, Nigerians or other foreign nationals, not GCC citizens.”

However, the recruiting companies, barring a few from free zones in the UAE, are owned by citizens. That they are not visible in the recruitment transaction is just an operational process, but business-wise they still stand to gain.

While direct recruitment was the norm until a few years ago, since late 2017 recruitment for all sectors in Qatar is through intermediaries, according to agents MR spoke to. Even the biggest companies prefer using HR consultants or recruiters based in the region. Though corruption in recruitment is not a new trend, it has become more formal and systemic in the last few years. Some labour reforms in Qatar that ease job mobility, such as the removal of No Objection Certificates and exit permits, are construed as detrimental to business interests: the employer would see the money invested in hiring as a loss. Consequently, this expense is passed on to the workers via the agents.

Across the board, agents say the demand for such high commission is a new practice. “Earlier companies were paying most of the costs. But from 2017-2018, things have gotten really bad. They (the client) say workers are able to change jobs easily so we must protect our interests. The demand letter from companies should be approved by the Kenyan National Employment Authority (NEA). But the language is such that you don’t indicate you are charging, it remains ambiguous. But trailing mails make it clear.”

A WhatsApp group of agents from around Kenya shares details of available jobs. One message for a job in Qatar reads, “Ready visas, male cashier jobs, salary 1800, commission 100k…” (the salary stated is in Qatari Riyals and the commission in Kenyan Shillings).

There are a few exceptions. The UAE’s Jumeirah group, Saudi’s Almarai, and Qatar’s Mowasalat and Abdullah Abdulghani and Sons are a few names that are mentioned repeatedly as following good practices. “They come to us directly, and even if they reach us through a middleman or HR company, their officials engage with us. They make it clear that though the HR company has their mandate, they would pay them directly and that we need not pay anything,” according to one agent. “Everyone else interacts only through the middleman, who in turn charges high fees per job visa. The majority of these HR companies conduct the interviews online via video call or over a phone call.”

Agencies at origin are not blameless. Contracts signed at home are unclear on working hours, wages and overtime calculations, and are vastly different from what they sign at destination. There are 542 NEA-approved private employment agencies (of the 758 listed) in Kenya. As in other densely populated countries, sub-agents work informally (and illegally at times), scouting for potential migrants. These sub-agents disappear or refuse to cooperate once they’ve taken a commission and connected potential migrants to the main agents. Workers MR interviewed say they receive little or no support once they’ve left Kenya (see Security Sector). Workers believe that the agents are being paid both by them and the businesses, and have little trust or belief in the transparency in the recruitment process. They all complain of lack of support once they migrate and face trouble.

The NEA is supposed to monitor the activities of the agencies. But Alexander Mbela, an activist (with Haki Africa, a Mombasa-based human rights NGO when interviewed), says politicians own many of the recruitment agencies either directly or by proxy. He also points out that unless there is public pressure, either on social or mass media in Kenya, embassies do not come forward to help workers in trouble in the GCC.

Demand for security bond and kickbacks

Documents reviewed by MR indicate that the most rampant corruption and charging workers fees is in the Kenya-Qatar corridor.

HR consultants or recruiting companies – who primarily recruit for the security and hospitality sectors – expect to be paid a fee per job order. Some of the names that are mentioned often include:

- International Human Resource & Hospitality Services (IHRHS) which recruits for Porto Holding;

- Power International Holding which recruits for Urbacon Trading and Contracting Company (UCC);

- UAE-based Dewan Consultants that recruit for Qatar and other GCC states;

- Compass Qatar that provides food and catering services;

- European Guarding and Security Services Company (EGSSCo);

- And recruiters that provide manpower for security and hospital services (or training of recruits) such as Colombo Manpower, Al Dahreez, Al Jassim, ISC Group, BSS, and Doha Security Services.

Unsurprisingly, some of these companies have been scrutinised in the past for poor labour practices. (see History of bad practices)

“Porto Holding, for instance, recruits a lot from Kenya, and they use IHRHS and others too. These HR companies insist that they pay the main company these unaccounted commissions. Very often, we only know of the HR company. We have deployed workers to work in McDonald’s, Burger King* and other international food chains there, through these HR companies and middlemen. Because we don’t have direct contact with their client, when there is a problem it becomes complicated to resolve. One of the HR companies that recruited through us for an international restaurant chain broke their contract with that company. People we recruited were working there and had some problems, but the company we had a relationship with could do nothing. Even if those international clients have good employment practices, their recruitment practices are not clear.”

*(IHRHS client list includes the Al Mana group, which holds the franchise rights for McDonald’s in Qatar. Dewan Consultants lists Burger King as one of their clients. Interviewees mentioned names of these brands and companies, but did not mention which HR company recruited for which brand.)

An agent based out of Nairobi, who has been operating for over 20 year, is part of the nascent ethical recruitment movement in the country. They deploy healthcare workers to the US and UK and semi-skilled workers mostly to Qatar, as drivers, security guards, technicians. A two-room office with a large bulletin board advertises available jobs, alongside a poster that says it’s a corruption-free zone. “There are (Gulf) companies that ask for money and when we decide not to, we lose business. On an average, it is about US$500 per visa. We also have to provide business class tickets and five-star accommodation when they come to conduct interviews. Workers end up paying for the processes,” the manager says. “Saying no to these demands comes at a great loss, as there are hundreds of agents that are eager for business, and will charge workers to cover these expenses and for their own profits.”

They share recently received RFPs and emails that demand a fee for every job visa. “Here is the evidence of a company that demands a credit note or guarantee that when workers resign or change jobs, they have to be compensated. They say it’s to refund their expenses, but what they demand is a far higher amount, almost punitive.”

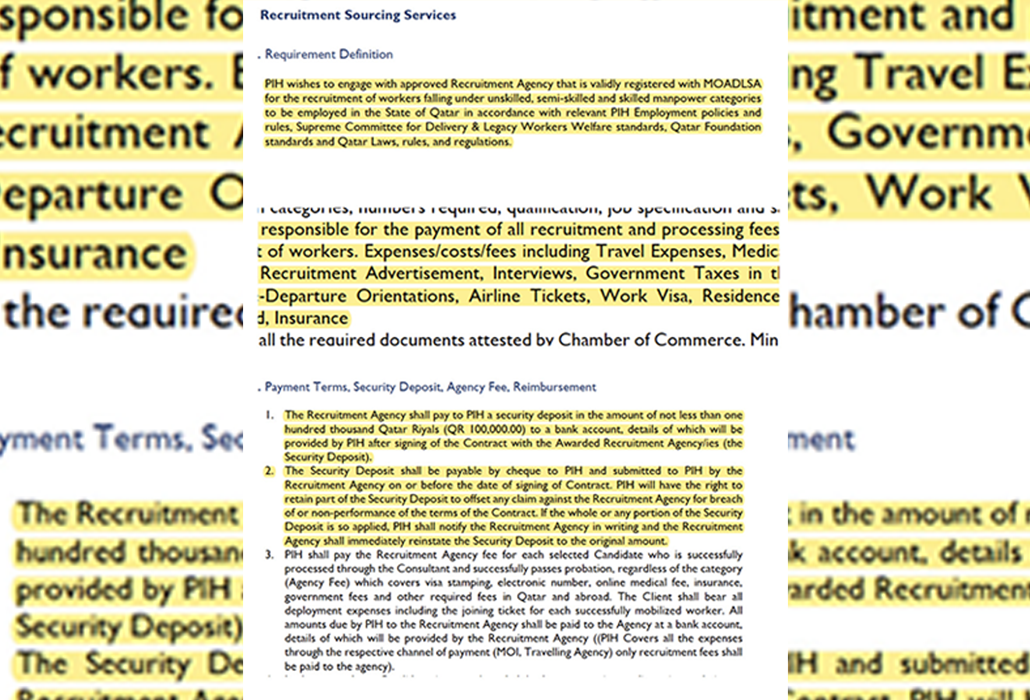

The RFP from Power International Holding (PIH), which owns and recruits for UCC Holding specifies the workers’ welfare standards of both the Supreme Committee for Delivery & Legacy (responsible for the 2022 World Cup) and Qatar Foundation (4.1), and further states that PIH would bear all costs related to visas and tickets [4.3 (4, 19); 4.4 (3)]

However, the RFP also states [4.3 (7)] that “[D]uring the recruitment campaign, Agency to arrange interview venue, interview schedules, airport pickup to and from the airport, carry the domestic tickets as per the itinerary for PIH representatives and all other necessary assistance required as well as all the required documents from government to conduct interviews.”

The agents who received this RFP say these are the expenses that remain uncovered.

The most problematic and expensive provision of the RFP is the demand for a security bond — in clear violation of the ILO’s fair recruitment principles — under the section ‘Payment Terms, Security Deposit, Agency Fee, Reimbursement’ [4.5 (1,2)].

“1. The Recruitment Agency shall pay to PIH a security deposit in the amount of not less than one hundred thousand Qatar Riyals (QR 100,000.00) to a bank account, details of which will be provided by PIH after signing of the Contract with the Awarded Recruitment Agency/ies (the Security Deposit).

- The Security Deposit shall be payable by cheque to PIH and submitted to PIH by the Recruitment Agency on or before the date of signing of Contract. PIH will have the right to retain part of the Security Deposit to offset any claim against the Recruitment Agency for breach of or non-performance of the terms of the Contract. If the whole or any portion of the Security Deposit is so applied, PIH shall notify the Recruitment Agency in writing and the Recruitment Agency shall immediately reinstate the Security Deposit to the original amount.”

The subsequent paragraph states that PIH would pay a fee to the agency “for each selected Candidate who is successfully processed through the Consultant and successfully passes probation…”

While the security deposit amount is clearly stated, there is no mention of the fee amount payable to the agent.

“QR100,000 is approximately KES3.3 million (US$27,500). How can we afford this deposit, and how do we even claim it in Qatar if this is misused by our client,” asks one agent.

PIH’s recruitment practice is not an exception. Dewan Consultants recruit for some of the largest groups in the region, including multinational brands, such as Ikea, Burger King, KIA, Jotun, Damac, Al Shaya Group, Saudia, Unilever, 3M and Al Emadi Group.

One contract recruiting workers for various Gulf states clearly states that the agent (second party) must pay Dewan Consultants (first party) US$200 per candidate and provide air tickets and five-star hotel accommodation for “2 delegates travelling for the interview.” (See Screenshots)

“We have no connection with the final employer, maybe the middleman is being paid by both parties, we have no way of knowing that. For ethical recruitment, the employer meets most of the fees and costs of air tickets. For the most part, at least for Qatar and sometimes the UAE, they don’t do that. We have had good experiences with companies in Qatar like Abdulghani or Jaidah motors who recruit drivers.”

Security Sector

The highest commissions are paid for jobs in the security sector. MR interviewed around eight aspiring migrants and 10 returnees who worked in the security sector, all of whom either paid hefty fees or are in the process of gathering funds to pay the demands. The fee demanded of late can be anywhere between KES120,000 to 200,000 (US$1000-1700).

EGSSCo, for instance, has procured more security contracts in the run-up to the World Cup and stepped up Kenyan recruitment in the last year. Kenyan agents that have engaged with the company say because the company has a significant size of job order, their demand for commissions cannot be turned down without impacting business locally.

In Nairobi, a group of seven recruits who had either worked in the GCC or were on the cusp of migrating, told MR they paid between KES100,000 and KES200,000.

William and Maxwell had both worked for GSS Certis in Qatar for two years. Both returned in 2021. In 2018 William paid KES110,000 (US$935) for the job, and earned QR1400 (US$380 per month, including overtime. Maxwell paid KES120,000 and received a similar salary. They worked a minimum of 10 hours a day, seven days a week. William had borrowed from his sister to go to Qatar and sent all of his money for three months to pay her back.

Maxwell says he did not complain and decided to complete the contract period and return. “We are in someone else’s country, so what can we say or do? The agent cut us off as soon as we left Kenya, so we couldn’t seek help there either.”

The fees workers pay for other GCC states is slightly lower. Raymond and Ismail both worked in Saudi Arabia and paid KES70,000 (US$600) each to secure a job.

Aspiring migrants Butros, John, and Jared listen to their compatriots with detached curiosity. The anecdotes of cramped living quarters, long work hours, and inadequate compensation do not deter them. John plays football for a local club and has been saving his earnings in order to pay the recruitment fees. “I have friends in Qatar, and they say it is better there. But I need at least KES100,000 in hand to find the job. I will also have to borrow since I won’t earn so much with football.”

Jared is also scouting for jobs in Dubai. “I’ve been promised a salary of KES70,000, but I have to pay the fees of KES100,000. I will sell my car and borrow from my family.”

In Mombasa, Mzee says he had a job lined up, with a visa issued from Saudi, but was not allowed to fly because he could not pay the agent the KES50,000 commission. “I told them I will pay with my salary, but they refused,” he says, showing the unused job visa. His friend James has been through a similar ordeal a few years ago. “The commission is even higher now. I have to raise KES100,000 to 150,000,” says James.

Though they have friends in the GCC and job leads, they say they cannot migrate without the help of an agent. The friends do not share particularly hopeful stories. “One of my friends told me even if you sign a contract for 10 hours you will be forced to work for 14 hours, but not get over time. You can’t complain or refuse,” says Mzee.

James interjects, “Nothing comes easy, no? We have to try and it is very difficult here (in Kenya) now.”

Some frequent complaints come from security guards who are overworked and uncompensated for their time.

“Everywhere they work long hours. More than 12 hours. The problem in Qatar and other Gulf countries is that they are not properly compensated for that,” says an agent in Mombasa who recruits for various security companies across the GCC.

A recent Amnesty report found that security guards in Qatar are subject to forced labour, “29 of the 34 security guards told Amnesty International they had regularly worked 12 hours a day, and 28 said they were routinely denied their day off, meaning many worked 84 hours per week, for weeks on end.”

History of bad practices

Power International Holding recruits for Urbacon Contracting and Trading Company (UCC). UCC, which is building several projects in Qatar’s Al Wakra town, a major touchstone of the World Cup events, as well as the View hospital in collaboration with Cedars-Sinai, has been accused in the past of misusing project visas to bypass regulations of the Qatar Visa Centres.

In March this year, UCC workers were amongst those who staged protests in Qatar complaining of unfair working conditions and compensation. An excerpt from our report:

UCC Workers MR spoke to say there are two main concerns currently: one is the lack of proper overtime compensation. The second is the repeated extension of short-term visas, with each term not extending beyond three months. According to workers MR spoke to, hundreds are currently employed on short-term visas. Under these short-term visas, workers end up working for a couple of years, but without a QID, health card or end-of-service benefits. “To go to a private doctor is very expensive and we can’t afford that. The company is not helping us. Also, so many of us are working such long hours and as some projects wrap up, we are being sent back without our gratuity,” according to one worker from India.

Earlier this week, Doha News reported that UCC employees were informed they would have to work additional hours each day, and on Fridays – the standard rest day for non-shift workers – and that they are being forced to do so without overtime pay. In its response to the news portal, UCC said the additional hours were optional, and “compensated in accordance with the Labour Law.”

In April last year, workers employed by European Guarding and Security Services staged a strike accusing the company of violating the Qatar labour law. Documenting the case, the Business and Human Rights Resource Centre writes:

An investigation carried out by the Qatari authorities found that all workers’ wages according to the new contract complied with the minimum wage threshold. However, the authorities found that the new contracts include a clause stating that workers must work for EGSSCO for at least five years and are not allowed to change jobs during this period. This clause violates Qatar labour law’s non-compete clause that abolished the legal requirement for migrant workers to obtain permission from their employers to switch jobs (no-objection certificate).

The Qatari authorities have confirmed that they have taken necessary actions to resolve the violation with the company and ensure the workers’ rights are met.

Processing Costs

As per Kenya’s Labour Institutions (Private Employment Agencies) Regulations of 2016, a minimum capital of KES 5 million is required to set up a recruitment agency.

The regulations stipulate that agencies are allowed to charge the principal (client) service fee for recruitment, documentation and placement of workers, and that all costs associated with visa fees, airfare and medical examination must be borne by the agents or employer.

The only ‘reasonable administrative costs’ that can be charged to the workers are for trade and occupational tests and administrative fees that cannot exceed one month’s salary as proposed in the contract. However, ILO’s guidelines on fair recruitment consider these expenses as part of recruitment costs and therefore not chargeable to the worker.

There is no Qatar Visa Centre (QVC) in Nairobi yet, so the processing is done by multiple agencies on the ground. QVCs are run by Qatar government agencies to provide integrated last-mile services that help reduce contract substitution and fraudulent medical tests. In its absence, workers have to reach out to multiple facilities to meet paperwork requirements. The medical clearance is done by Gulf Approved Medical Centres Association (GAMCA) and other processing by the Qatari embassy in Nairobi through BLS International Services.

“These costs add up. The police clearance certificate needs to be stamped by the Qatar embassy. For the certificate and stamp from Kenyan Ministry of Foreign Affairs you pay KES 1050 and 200 respectively. However, the Qatar embassy has outsourced the stamping service to BSL, which charges US$38. Earlier the embassy charged US$30. All of this is usually paid for by the worker. Very few clients cover these costs. It is very rare.”

Inadequate mechanisms

According to different recruitment associations in Kenya, some of the big contracts and RFPs are negotiated by the Kenyan embassy in GCC states where they have a bilateral agreement, even if the terms are often unclear and unfair.

There is no consultation with recruitment agent associations when these agreements are finalised, even though they are a key stakeholder in the process of deploying Kenyan workers.

“The Kenyan government does not involve us in bilateral discussions. We are not able to tell them or the destination governments how we are charged. They go alone for these negotiations. Also, these officials are appointees and are easily replaced, so there is no institutional memory of the problems or how to solve them,” according to the head of KAPEA.

While ethical recruitment frameworks establish many important principles, the discourse tends to focus on poor regulations, practices, and rampant corruption in origin states without considering the chain of corruption that leads back to the countries of destination. Origin states have some regulations, however weak their implementation may be. In contrast, there is little or no regulation and monitoring of HR consultants and recruitment companies in destination. For workers to prove that they were charged illegal fees, fingers must point to an agent at home, regardless of whether the demand was, at least in part, due to fraud and corruption in destination. These massive institutional gaps fail to achieve the primary objective of fair recruitment – to eradicate debt bondage and protect the rights of migrant workers.

- BSS is, and always has been, a training company not a recruitment company

- BSS has never had contact with recruitment companies in Kenya or elsewhere for positions in the Middle East or other countries

- BSS provide training to companies and individuals:

- If a company requests training for their staff they pay for it

- If an individual person approached BSS to attend one of our training courses, obviously such an individual would pay for the training they requested and attended

The original paragraph [“And recruiters that provide manpower for security and hospital services such as Colombo Manpower, Al Dahreez, Al Jassim, ISC Group, BSS, Doha Security Services”] has been edited to reflect this information.

What is Fair and Ethical Recruitment?

Some key points of the ILO’s General Principles and Operational Guidelines for Fair Recruitment are:

- No recruitment fees or related costs should be charged to, or otherwise borne by, workers or job seekers.

- Freedom of workers to move within a country or to leave a country should be respected.

- Workers should be free to terminate their employment and, in the case of migrant workers, to return to their country.

- Migrant workers should not require the employer’s or recruiter’s permission to change employer

- Governments should take steps to ensure that workers have access to grievance and other dispute resolution mechanisms, to address alleged abuses and fraudulent practices in recruitment, without fear of retaliatory measures including blacklisting, detention or deportation, irrespective of their presence or legal status in the State, and to appropriate and effective remedies where abuses have occurred.

- Governments should take steps to protect against recruitment abuses within their own workforces and supply chains, and in enterprises that are owned or controlled by the government, or that receive substantial support and contracts from government Agencies.

- Workers and job seekers should not be charged any fees or related recruitment costs by an enterprise, its business partners or public employment services for recruitment or placement, nor should workers have to pay for additional costs related to recruitment.

In addition to charging workers recruitment fees, laws and regulations in both destination and origin contravene these guidelines. Difficulty changing jobs, lack of grievance mechanisms, threat of detention and deportation for highlighting violations are all real and valid concerns faced by workers.

Furthermore, according to the Principles and Guidelines, the following are costs considered related to the recruitment process:

- Medical costs: payments for medical examinations, tests or vaccinations;

- Insurance costs: costs to insure the lives, health and safety of workers, including enrollment in migrant welfare funds;

- Costs for skills and qualification tests: costs to verify workers’ language proficiency and level of skills and qualifications, as well as for location-specific credentialing, certification or licensing;

- Costs for training and orientation: expenses for required trainings, including on-site job orientation and pre-departure or post-arrival orientation of newly recruited workers;

- Administrative costs: application and service fees that are required for the sole purpose of fulfilling the recruitment process. These could include fees for representation and services aimed at preparing, obtaining or legalising workers’ employment contracts, identity documents, passports, visas, background checks, security and exit clearances, banking services, and work and residence permits.

Kenya’s regulations allow for charging workers for many of the above costs. None of the GCC states have a post-arrival orientation for new recruits.

Under Illegitimate, Unreasonable and Undisclosed Costs the guidelines state that “Extra-contractual, undisclosed, inflated or illicit costs are never legitimate. Anti-bribery and anti-corruption regulations should be complied with at all times and at any stage of the recruitment process. Examples of such illegitimate costs include: bribes, tributes, extortion or kickback payments, bonds, illicit cost-recovery fees and collaterals required by any actor in the recruitment chain.”

While undocumented bribes are difficult to prove, bonds and cost-recovery fees are blatantly included in contracts, but escape criticism.