What happens when no one’s looking?

Malcolm Bidali reflects on the last 12 weeks of detention, intimidation, and being charged for a ‘crime’ of highlighting the plight of lower-income migrant workers like himself

So much has happened over the last three months, fueled by events in the months prior to those. Long story. I will (attempt to) be brief.

On 4 May 2021, I was handed over to the SSB, Qatar’s State Security Bureau to be interrogated about my activity on migrant workers’ rights. Here’s how that went down.

At around 7 or 8 pm, the ‘camp boss’ at the accommodation sends for me. I try to ask the security guard, his head peeking into my room, what all that’s about. He says he doesn’t know. I take a guess. Could be about vaccination? I was among the few who hadn’t gotten it yet. But, if it was about the vaccine, they would have called me on the phone or sent one of the camp officials with a document of some sort for me to sign. Weird. Maybe they want me to sign it at the office. Or, maybe, the company somehow, finally figured out my secret. But, even then, they would have called me on the phone and told me to come to company headquarters the following day. Or, they would have sent a camp official to relay all this.

I grab my phone and my portable Wi-Fi and go through these scenarios as I make my way down four flights of stairs and walk to the camp office, the security guard following closely behind. I get to the administrative office, and I’m asked to have a seat. Heart is racing. Mind is on overdrive.

I grab my phone and my portable Wi-Fi and go through these scenarios as I make my way down four flights of stairs and walk to the camp office, the security guard following closely behind. I get to the administrative office, and I’m asked to have a seat. Heart is racing. Mind is on overdrive.

The camp boss is on the phone, pacing back and forth. People stream in and out of the office. Some dropping off or collecting their laundry. Others checking the notice board. Others just seem to hover about.

Done with the call, the camp boss turns his attention to me, smiling. “Malcolm, how are you? How are things at work?”

Big red flag. He has never been this civil with me. I say I’m good, work is good. Unlocking my phone, I ask for the reason behind my summoning. “Our company PRO wants to speak with you.” Huh, who now? “The PRO. He wants to see you at the main office. I’m just trying to arrange a vehicle for you.” (Much, much later, I confirm that PRO means Public Relations Officer, better known as the mandoop.)

Another red flag. Pretty sure no one’s at the office at this time. Especially since it was Ramadan. I try to inquire about the nature of this impromptu meeting. Why does this guy require my audience? “I don’t know, you will discuss that when you get there. Just wait for the transport…” he says, as he gets on the phone again. I overhear “… the MOI” in the conversation. I unlock my phone again. That’s the Ministry of Interior. Yeah, I’m in trouble.

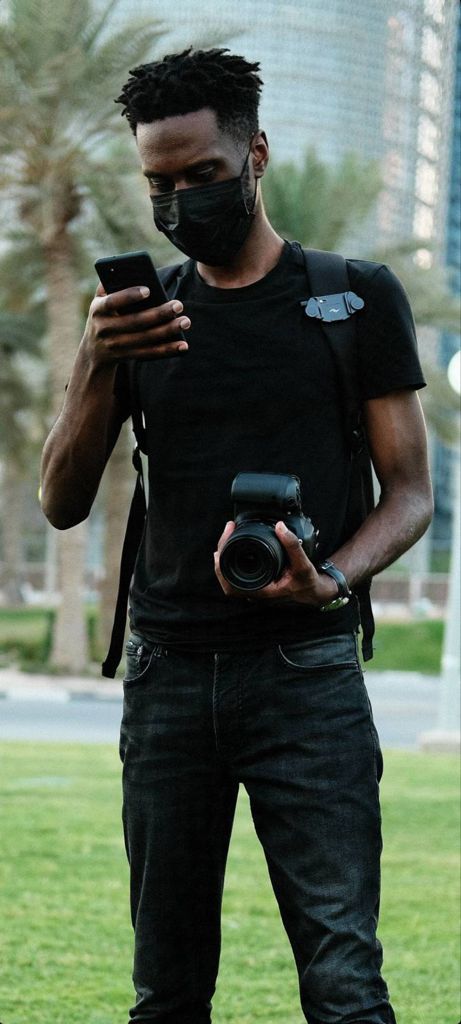

I fire up WhatsApp, and compose a message to someone who knows of my work. “Possible SOS.” Send. They might not even see it on time. Okay, what next? I send another message, brief, with key details of my summoning and that I’m about to be transported. The driver appears outside the office, standing, waiting. I become aware that whatever this is, it’s a very real situation, and all I have is the t-shirt I sleep in, a thin sweater on top of that, and the work trousers I slid into as I left the room. And sandals. I tell the camp boss I’m going to change my attire. He thinks about it, then agrees. Splendid. At least I’d get deported with warm clothes and some actual shoes on. The security guard shadows me to my room. He is way too close. Back up bro. We exchange some words on the way. In the room, I put on a black t-shirt, black denim jacket, a black cap, and some white-soled black sneakers. The black work trousers stay on. I grab my Qatar ID, some cash, and my Doha Metro Card. Just in case.

I’m led to the main gate as I begin deleting contacts, messages, and emails. The driver brings the minivan around. I get in and settle in the back. The security guard gets in as well, and we’re off. By this time, my contact has seen and responded to my messages. Okay, so, initially I thought I was being taken to the airport, but the driver now takes a different exit, heading towards the city itself. Things are definitely getting more interesting. I update the contact on this development. They ask how I’m feeling. I say I’m nervous, but I’ll put on a brave face when I get there. As we get closer to the destination, I recognise the structure from an intersection some distance away. The Ministry of Interior building has this simple but iconic facade, reminiscent of traditional Qatari architecture. And it lights up remarkably well at night. One of my favourite buildings in Qatar. I fell in love with it way back in 2016, as I gazed, wide-eyed, out of a Karwa bus window.

So, we get past the intersection, drive up to a special entrance and the driver parks a few feet away from the gate. There’s military personnel present. The driver, already on the phone with someone from the company, is asked to state his business. He either hands the military guy his phone or relays a message. Can’t quite recall. I’m on my phone. I send my location and describe what I see around me. I manage to send my location and send an SOS to another contact too. I look up and see some figures approaching. The minivan door is opened and I see two guys dressed in local attire. One of them, the shorter one, orders me out. There’s something about how he said it. It wasn’t just a plain order, it was filled with contempt, disgust, as if harbouring a grudge. I knew I was in trouble. I get up from my seat, hunching over as I make my way out. “Phone!" he barks. No time to say goodbye to anyone. I hand him both phones (The Nokia E7 will be missed. I’ve had it since 2016.). One uniformed officer pats me down, relieves me of my effects, handcuffs me, and leads me to the Land Cruiser parked a few feet away. The two SSB personnel get into the front, and I shuffle into the back left. The uniformed officer is to the right. The interior smells like tobacco and oud. The vehicle begins to move, and as I’m whisked away to interrogation, I can’t help but think, “How did I get here?”

“Once I saw the power of words, social media, and civil society, I was hooked. I saw that I could truly make a difference in other migrant workers’ lives, and I dived in head-first, even when it was super risky to do so.”

Well, that is an even longer story. I’ll be brief.

I stumbled into advocacy. I never quite intended to be as involved as I am now. Certainly not as involved as to invite interrogation and be forcibly disappeared by the authorities. So, how did I get here? Well, I can trace the origins to a certain accommodation structure in Qatar’s Industrial Area, where low-wage migrant workers are housed in slum-like conditions, away from the general population. Our company, GSS Certis had been housing us there. And at the time (late 2019), we were working at Msheireb Downtown Doha, the flagship of Msheireb Properties, which is a subsidiary of Qatar Foundation, an internationally recognized beacon of change.

So, right before we started working there, word went around that this project was directly connected to the ruling family, and we, as the security guards, knew that life was going to get better for us. There was even speculation that we would be shifted to a better accommodation because there was no way you could work at such a prestigious location, and live in the Industrial Area. Not possible. Yet, there we were.

A couple of weeks after we began working, Msheireb Properties came to inspect the accommodation and apparently, they found nothing wrong. To add insult to injury, camp officials had come into the rooms while we were at work and shuffled our belongings around, squeezing and fitting them wherever space was available, like real-life Tetris. All this just so that the room could look more spacious, more presentable, to the Msheireb Properties staff. In the process, some of my possessions were damaged, and that is what sparked the flame for me.

That evening, after visiting Msheireb Properties’ website (MP), I saw there was a whistle-blowing section to report issues. After much thought, and even more fury, I created an anonymous email account and wrote to them. They did respond, and said they would raise the issue with the concerned departments. But nothing came of it. Fast forward to the pandemic, and we had been shifted to another accommodation, with even more people per room. I reported this to MP, QF, the Ministries of Labour and Interior, but no action was taken.

Around this time, I was introduced to other human rights advocates with whom I shared a journal entry of mine, describing my situation. That journal entry became my first article for Migrant-Rights.org. Aided by Twitter’s nature, the story got a lot of traction, and when we were shifted back to our original accommodation, our living conditions were changed almost immediately. That is when I understood that speaking up leads to change.

Once I saw the power of words, social media, and civil society, I was hooked. I saw that I could truly make a difference in other migrant workers’ lives, and I dived in head-first, even when it was super risky to do so.

And that is part of how I found myself a guest of the State Security Bureau. During the interrogation, they kept asking why I was “against Qatar.” They wanted to know all the organisations I worked with. All the people from said organisations who I was involved with. They wanted to know how much I was paid to publish “untrue things”. They even wanted to know why I supported women’s rights during that shameful and disturbing incident at Hamad International Airport. (They pretty much asked everything else, yet they steered clear of one particular subject. I expected them to ask me about it, but they didn’t. Very strange.)

They demanded and – after futile resistance on my part – got my PINs, passwords and credentials for my phones, Instagram, Twitter, Gmail and PayPal. Even my M-Pesa (Kenyan mobile money wallet). They had access to everything – emails and chats I hadn’t deleted yet, my photos, my journal, my contacts. None of those were incriminating, just not something I’d want them to have. And that’s not even the worst part. The fact that I gave them access is what disturbs me. Maybe I should have resisted more. But as the officer said, “You think we don’t already have them?” According to him, they wanted to see if I was being cooperative or not, which would then dictate how lenient they, and eventually the court, would be. I figured, even if they tortured and killed me for not sharing anything, they would probably break into my phone eventually, rendering my silence irrelevant; in vain. At least that’s what I told myself.

None of the contacts I had on my phone can be described as 'against Qatar'. These included individuals from the ّInternational Labour Organisation, which works closely with the government. Correspondence will show that I really wanted to be involved in labour reforms. Some contacts, who the authorities described as ‘enemies’, even collaborated with the Ministry of Labour and National Human Rights Committee. Enemies? Really?

“What if someone else, who isn’t as lucky to have a ‘network’, decides to speak up? What then? How much more will they suffer at the hands of the state?”

However, looking back at that particular incident, I could have handled it very differently – by not having anything relevant on my phone in the first place. But that’s a story for another day.

From the onset, I was denied a lawyer. I had watched enough movies and TV to know I at least had the right to a lawyer and/or one phone call. I made it very clear to them that I needed to have and speak with a lawyer. They told me that as long as I was under their custody, I didn’t have any rights. The lawyer request was dismissed, and they said that I was there to only answer questions. Access to a lawyer would have to wait until I was taken to court. I asked when that would be, they said they didn’t know. When I asked what I was being charged with, they also said they didn’t know.

When I was finally taken to the Public Prosecutor, after two weeks, he began interrogating me, again without a lawyer present. I protested and asked for one. He asked me, “Did you come with a lawyer?” I obviously hadn’t. And with that, the interrogation proceeded.

After three days with the Prosecution, I was made to sign another document, all in Arabic. The two charges he informed me of officially were, 1) Creation of social media accounts for the purpose of spreading disinformation. 2) Spreading disinformation through the social media accounts. I obviously denied these charges, because nothing I wrote was ‘disinformation’. Imagine my surprise when I was released and read in the media that I was being charged with “offences related to payments received by a foreign agent for the creation and distribution of disinformation within the State of Qatar”. That was later dropped and I was informed that they were considering charging me with “revealing company secrets.” That was dropped as well, in favour of “establishing and publishing false news with the intent of endangering the public system of the state”, and a QR 25,000 (US$6900) fine for good measure. A deterrent to anyone human enough to exercise free speech.

The odds were never in my favour to begin with. There was no way I could afford a lawyer, and no way I could afford to pay any fine they set. It’s only a miracle that I knew some people from civil society groups, and they moved heaven and earth to ensure I was released and all my bills were paid. I don’t think the authorities expected such overwhelming support for an African security guard, and frankly, neither did I. This got me thinking, “What if someone else, who isn’t as lucky to have a ‘network’, decides to speak up? What then? How much more will they suffer at the hands of the state?” I believe everyone should have the right to speak up and raise their voice in the face of injustice, and the government should in fact encourage this. Sadly, we don’t live in that kind of world.

“...unity is discouraged and often, a few individuals, labelled as ‘troublemakers’, are deported to keep everyone else in line. Among us workers, there is a saying, “My friend, I came here alone.” This is to imply that one has no obligation to be involved in any collective bargaining, because they want no part in the retribution that usually follows.”

So, how has all this affected my view of migrant workers’ rights?

Well, for one, I feel like that whole situation really opened my eyes to just how crucial the fight for labour rights is. Qatar chose to detain me rather than to acknowledge and address the issues we face. That makes no sense. Why would they do that? Wouldn’t it have been better to approach me and ask me to collaborate with them? Qatar’s labour law actually outlines very decent standards for workers and it’s the wayward employers who mess things up. Usually very connected, influential, wayward employers. The labour law, the Workers Accommodation and Planning Regulations, and Qatar Foundation’s Workers Welfare Standards are what I used as my guides in our situation, and I believe that the standards contained within should be the minimum afforded to any migrant worker. No one deserves to be jailed for saying that.

Second, it showed me just how important civil society is. All the institutions, organisations, and like-minded individuals really came through for me and helped with the campaigns, media coverage, legal representation, and payment of the fine. I consider myself blessed to have had this kind of support, and I urge anyone who can, to speak up and support the fight for workers rights. Even simple things like retweeting and reposting really go a long way! A post or a tweet may be the difference between life and death, freedom and imprisonment. Civil society groups are essential in the fight for human rights and I cannot stress that enough!

Also, this whole incident has strengthened my resolve. It has made me want to do more, especially when I remember the first two days (of the 28 total) in solitary confinement, the tiresome interrogation, the exaggerated charges, the travel ban, and the obscene fine. I remember all that and it just fuels me. Plus I know the labour situation is far from ‘ideal’, so there’s more work to be done.

That being said, Qatar has made some reforms, probably the most within the GCC region, one could argue. On paper, they look splendid, but on the ground, things are different. I would suggest allowing unions for all categories of migrant workers so that they can be seen and heard. What are you so afraid of? I don’t get it. I would also suggest facilitating dialogue regularly between workers and the Ministry of Labour. Speaking of ADLSA, it wouldn’t hurt to train and include migrant workers as labour inspectors. You need their perspective.

This one is for the authorities. How is it that you were able to track me down, apprehend, detain, and penalise me because of my free speech, yet you can’t do the same to those nefarious employers who physically and sexually abuse their domestic workers? And in some/most cases, the victim is the one who ends up deported. Who does that!? And where are the embassies in all of this?

For anyone within the GCC wanting to get into advocacy, I would suggest exhausting the formal avenues first, as I attempted at the beginning. Information is power. Qatar’s labour law dictates that workers live in decency and get their wages paid in full. I would urge migrant workers to read and be familiar with the labour law so that they can be able to confidently report, or take other measures when violations do occur. (I would also suggest reading the QF, Ashghal, and the Supreme Committee Worker Welfare Standards to just be familiar with what the benchmark is supposed to be.) The Ministry of Labour should also do its best to protect those who come forward because companies often mete out retribution to such individuals.

One solution is for workers to unite. There is strength in numbers. This way, they can raise their grievances collectively without the fear that comes with doing it as an individual. Qatar has seen a good share of peaceful strikes, with workers demanding their wages. The problem is, unity is discouraged and often, a few individuals, labelled as ‘troublemakers’, are deported to keep everyone else in line. Among us workers, there is a saying, “My friend, I came here alone.” This is to imply that one has no obligation to be involved in any collective bargaining because they want no part in the retribution that usually follows. And so, for most workers, it usually boils down to falling in line, keeping your head down, and going with the flow, which often leads to exploitation.

Finally, I can’t help but wonder what’s in store for migrant workers after the World Cup. If workers still live in horrible conditions, if workers still go months without pay, if workers still can’t freely change jobs, if domestic workers still can’t get justice, what happens when no one’s looking?

If I was unjustly detained and unjustly fined – while all eyes are on Qatar – what happens when no one’s looking?