Half a lifetime of toil, and all that’s left is charity

Muneer Sahib has spent more than half of his life in Bahrain. Now in his 70s, his story is that of thousands of other migrant workers who live in distress, denied their rights and wages.

Muneer Sahib's voice trembled with rage, sorrow and fear, his eyes revealing the broken trust in man and law. “We have run out of patience. We have completed the year and have not yet received our wages. We are waiting. Our families back home are waiting. We will be expelled from our place of residence, our health is deteriorating, and nobody listens. We went repeatedly to the Ministry of Labour, and they made unrealistic promises just to force us to leave.”

Muneer has just turned 70. He moved to Bahrain from India 38 years ago to work as an electrical engineer. In March 2019, he received his last salary from G.P Zachariades (GPZ), a construction company that has since gone bankrupt.

"At the beginning of 2019, we were working on a major government project that GPZ was contracted for when we decided to go on strike as the company had not paid our salary for two months. But then, we were surprised when someone who introduced himself as a representative of the Ministry of Labour asked us to return to work, claiming that because the project belongs to the government, our wages were guaranteed. So we went back to work on his word. But months have gone by and we still have not received our wages. This ‘official’ was nowhere to be found every time we went to meet him at the Ministry. Another official spoke to us and he promised us every time that he will enquire with the company. But, here we are still... ”

Future in peril

Muneer is one of the 52 workers still in Bahrain, out of the couple of thousand GPZ workers from India, Nepal and Bangladesh who changed employers or returned home either empty-handed or with less than what they were owed.

The company laid off most of its workforce, except those on government projects, after experiencing financial difficulties largely due to clients defaulting on payments. Some workers found jobs with other employers in Bahrain and those who were owed less than BD500 in end-of-service benefits were paid in full. The rest were promised their dues after liquidation. However, the company instead made a quick and quiet exit out of Bahrain, leaving these 52 workers in penury.

The total due to them is BD250,000 (USD661,000). Muneer alone is owed BD18,300 (USD48,396) – the sum total of his due wages, end of service benefits and airfare back home. The price tag on four decades of his life that he has invested in the company and the country.

Muneer is the eldest amongst his group, who now all live in an abandoned labour camp. They may soon be expelled from their accommodation, which had been rented to GPZ.

We are waiting. Our families back home are waiting. We will be expelled from our place of residence, our health is deteriorating, and nobody listens.

All of their residency permits have also expired, leaving them vulnerable to arrest and deportation. They spend their days worrying and counting down to the elusive day that will end their misery.

The Ministry had promised them that they would receive their dues when GPZ’s remaining assets were sold. So Muneer and his colleagues were taken by surprise when company managers left the country with the entire proceeds from the sales.

GPZ had gradually lapsed on its obligations over several months. For the first five months they stopped paying wages, they provided workers with food. Then they provided only a monthly BD20 food allowance, which they then reduced to BD10 before abandoning the workers entirely. Now the workers live on handouts from charities.

Life and death

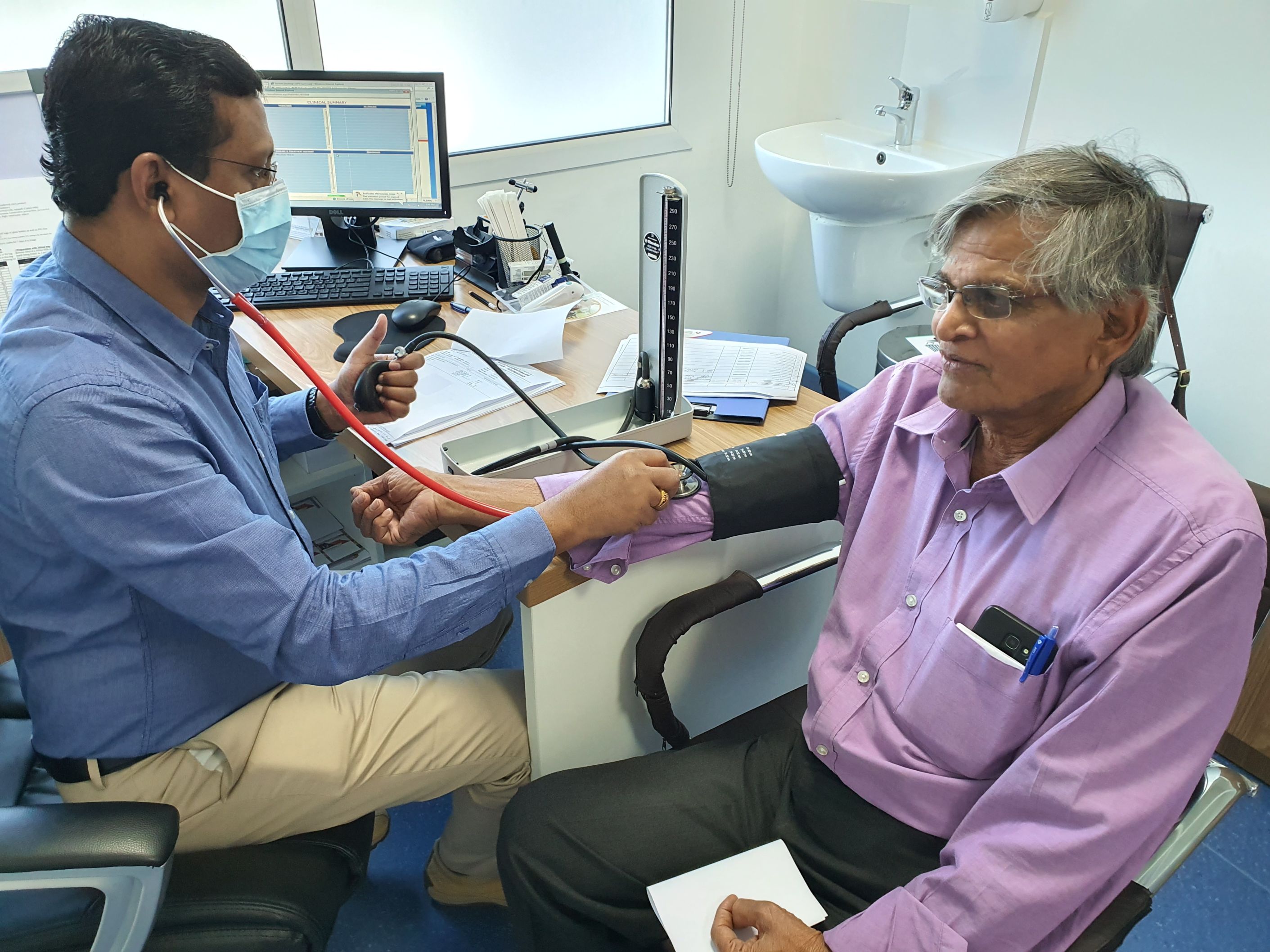

Most of these workers are elderly and have spent all their productive lives here in Bahrain, and mostly with GPZ. Many have chronic health conditions that require regular medication, check-ups, and monitoring. Following a free health examination arranged by the Migrant Workers Protection Society (MWPS) and Al Hilal Hospital, 43 of them were diagnosed with diabetes, high blood pressure, cholesterol and even kidney malfunction. Muneer’s conditions were amongst the most alarming. They received a month’s supply of medication for free, but with no money, their conditions remain precarious. For this again, they depend on charity.

Muneer at his health examination

GPZ workers have been battling illness for at least as long as they’ve been fighting for their wages; A year ago, a Bangladeshi worker died of a heart attack, while the workers were still fighting the company for their dues. In 2017, another worker from India died from an injury he received while protesting for his wages. Police had used teargas to disperse them.

Most recently, an elderly worker from Pakistan was paralysed and hospitalised for a month. Though his condition has improved, he is unable to obtain treatment or medicine.

Between hope and despair

The plight of Muneer and his GPZ’s colleagues is not unique. Non-payment of wages is a growing problem in Bahrain, particularly in the construction sector. Recent examples include 180 workers from Orlando Construction Company who have not been paid for several months, twenty workers from M&I company who have not been paid for seven months and 250 workers from Bahrain Motor Company who haven’t been paid for five months. Neither of these companies has an active project, and with no revenue in sight, these workers may end up in a long-drawn-out battle similar to GPZ workers.

There are another 2,000 other workers enduring the same plight. They haven’t received a full salary for the last five months. Their employer delays their salaries and then pays only a part of it, leaving the workers hanging between hope and despair. They preferred we not mention the name of their company as they fear it may jeopardise their case.

All of these cases are pre-Covid19, but the fallout of the pandemic has aggravated their situation, alongside those of thousands of other migrants in construction and other sectors. There is a danger that these cases will fall through the cracks as governments scurry to help local businesses at the expense of migrants workers. The crisis has shattered the remnants of any hope workers had to recover their dues as businesses face huge losses.

The Bahraini government must restructure the laws and institutions that consistently fail migrant workers, and must find a solution to control the humanitarian consequences that echo in countries far away. For every one worker affected in Bahrain, there is a family of three to four back home struggling for food, medicine and education. A high-level team must be formed to study immediate solutions and restores confidence in the power of the law and of the executive bodies that protect human rights of the workers.