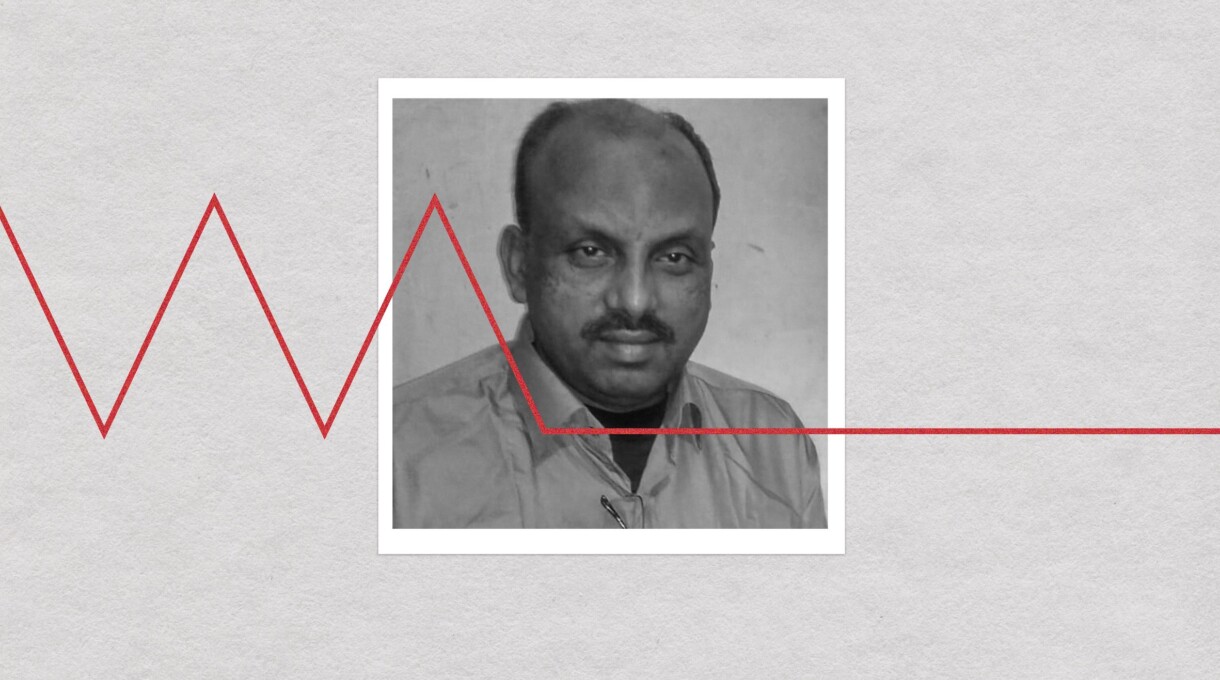

Former GPZ employee Muhammad Elias dies a year after leaving Bahrain empty-handed

38 years of service and shattered dreams

“My father died bitter. Every night he would share his story and lament – I spent my entire life in a foreign country only for my family, and now, at the end of my life, I can't even support my family. I failed, I can't obtain better medical care, I can't afford your schooling.”

Muhammad Elias, 65, died of a heart attack on the second day of Eid al-Fitr. In a stifled voice, his grief-stricken son Imtiaz explained that “four months ago, the doctor told him that he had to perform an urgent operation to correct large blockages in the arteries. However, because he couldn’t raise US$7,000 for the surgery, he could only take medicines that relieve the symptoms he was experiencing.”

Muhammad died while waiting for his overdue salary and end-of-service benefits, which totalled BD8000 (US$21,300) and would have covered his life-saving operation cost three times over.

He leaves behind his wife, Josna, 48, his eldest son, Imtiaz, 25, his daughter Zakia, 18, and his youngest son, Adnan, 12.

Muhammad was one of the thousands of migrant workers whose wages and end-of-service benefits were stolen for years by GP Zachariades (GPZ), a now-defunct construction company that had held public and private contracts worth hundreds of millions of dollars. After GPZ’s bankruptcy, funds collected from creditors were used to settle dues for some of its 2000+ employees. But a year after leaving Bahrain, Muhammad and 17 of his colleagues have still not received their settlement.

“...38 years later, Muhammad was in the same building that he helped build, failed by his employer and the system, seeking justice.”

The total due to these workers, who were employed by the company from three to 38 years, amounts to approximately BD197,000 (USD652,000), roughly equivalent to the cost of establishing a medium-sized villa with an area of 500 square meters in Bahrain. Individually, they are owed between BD3,500 to BD40,560 (US$7,089 to US$108,157) each in unpaid wages and end-of-service benefits.

Civil society organisations helped Muhammad and his colleagues maintain contact with Bahrain’s Ministry of Labour in order to receive their dues. The Ministry reassured them that consultations with the company and its debtors were ongoing, and that the money owed to them would be with them soon. With the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic, the company representative and the ministry asked the workers to return to their home countries and promised that their dues would be transferred to their bank accounts later. But the Ministry and the company did not keep their promise.

On 6 May 2021, Muhammad left empty-handed for his home country of Bangladesh. Imtiaz says that his father did not discuss the specifics of his financial problems with the family, but was concerned and nervous after his return. Imtiaz recalls him saying, "I had not anticipated being robbed of my savings in this manner. I've waited so long to get my dues, but there doesn't appear to be a solution."

Muhamad, who had worked on the quality control team, received his last salary payment on 30 April 2018. He worked for 15 months after that without pay because the company, and later government officials, pressured him and his co-workers to keep working, and promised to pay them once the project was complete. The company terminated his services on 30 July 2019, still owing him past-due wages, as well as his end-of-service benefit. He continued to live with colleagues in GPZ’s labour accommodation while waiting for his due, provided with only BD20 per month (US$53) for bare sustenance.

The final months in Bahrain were traumatic for Muhammad and his colleagues, who were neglected both by GPZ and government officials. They were housed in unlivable conditions, threatened with eviction when the employer failed to pay rent to the labour camp owners, and dependent on NGO donations for food and medical care.

Local and international media reports on the suffering of GPZ workers and their attempts to protest yielded no result.

After returning to Bangladesh, Muhammad kept in touch with his colleagues. He mentioned more than once in WhatsApp messages to them that he suffered from a health problem and desperately needed his money from the company. He also followed up on the progress of their case with GPZ and the Ministry, but all of his appeals were unsuccessful.

Tragic irony

During one of the visits to the Ministry, Muhammad told an official, "You know that when I first came to Bahrain in 1982. This building, the Ministry of Labour building, was the first project I worked on for GPZ." And, 38 years later, Muhammad was in the same building that he helped build, failed by his employer and the system, seeking justice.

In an interview before his departure, Muhammad said, "I feel very upset and sad. I feel ashamed to go back to my country after working for nearly 40 years, and ask for help and ask for money from others... No [I will not do that]."

A recent investigative report found that hundreds of thousands of migrant workers in the Gulf have experienced wage theft, the delay or deprivation of their wages and benefits.

At the time of writing, the remaining 17 GPZ workers are still awaiting their dues a year after their departure from Bahrain, and more than three years since the company stopped paying their wages. Their case is collecting dust in the drawer of the lawyer representing the workers, who has struggled with the lack of cooperation from government officials. Now, only the Ministry, which must complete the necessary procedures, stands in the way of collecting their dues.